(Gallery Thirty Three, Wānaka)

Collaborative summer exhibitions are an ideal opportunity to explore numerous voices and styles, showcasing the stars, hidden gems and newcomers in a gallery’s collection; however, there’s an art to effective curation — catering to a wide range of tastes without overwhelming the viewer. Wānaka’s Gallery Thirty Three never misses a step in its selection and celebration of talent, and this year’s "Summer Series" is another winner — both peaceful and exciting, charming and quirky, and packed with personality. Several of the artists and styles couldn’t be more different, yet there’s harmony and cohesion in the choice of works; it’s a masterclass in both abstract and figurative painting, and a goldmine for fans of sculpture.

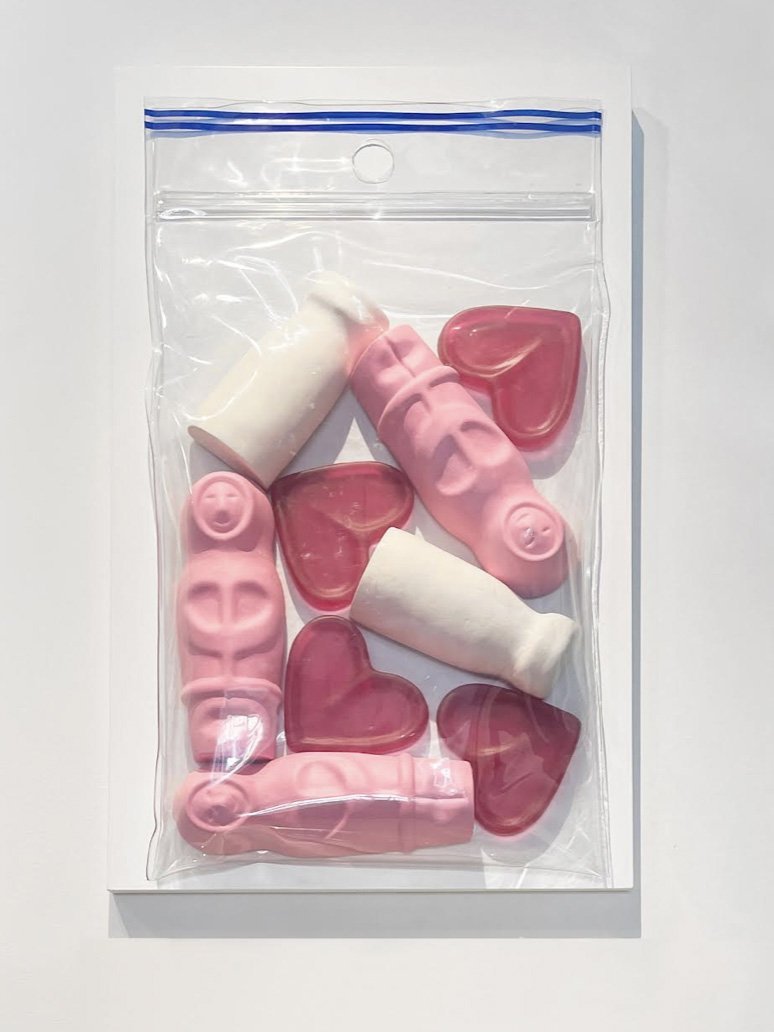

Ceramicist Heather Anne Atkins’ miniature village of historic cottages and villas are lovingly handcrafted, an homage to the 18th and 19th-century architecture of small towns and goldmining settlements. Simon Lewis-Wards’ ceramic and cast-glass lollies are reaching the same iconic status as their edible subjects, and behind the playfulness and retro whimsy is a consistently impressive level of technical skill and precision. Melissa Young’s work is a study of contrasts in action — minimalism of form invested with a maximum of feeling. The simplicity of her faceless, featureless, amusingly tiny-headed figures pushes all the energy into the elegance of captured motion and emphatic body language. The bronze sculptures are dark and monochromatic, yet her figures are bold and communicative, embodying the shadows but living in the light.

(Hullabaloo Art Space, Cromwell)

Throughout history and as long as humanity endures to pick up a brush or clay, art will always convey — either explicitly or covertly — the state of the artist’s world, on both a personal and global level. Artists are entertainers and creators, but also storytellers, archivists and activists; and during times of particular global strife and hardship, an underlying tension and sense of slipping security is often reflected in new work. Sue Rutherford’s latest collection, "Lands End", explores the collision and collaboration between people and the natural environment, but the clever imagery resonates in multiple — and literal — layers.

Despite leaving a deepening footprint on almost every corner of the Earth, humans are still only one species of many in a long, unfolding story, vulnerable to the passage of time, the powerful forces of nature and the consequences of our own actions. In a striking series of ceramic sculptures and vessels, Rutherford crafts homes and buildings teetering on clifftops and weathered precipices, layering texture to imitate the effects of erosion. Lattices are carved into the foundations — the columns appearing first rather like tree trunks or ladders, a fight for dominance against the landscape and each other, always trying to ascend higher, never satisfied; and then creating the illusion of an exposed rib cage. We coexist with the land, rely on it for survival, yet wear it down to its bones. Hollows are appearing, the ground is crumbling and the ultimate fate of the dwellings is as yet unknown.

(Eade Gallery, Clyde)

Through the gorge at Clyde’s Eade Gallery, Debbie McCaw and Lynne Wilson’s "Footprints" also delves into the relationship between people and the land, here with a more specific local focus, tracing a path through the gold trails and ancient peaks and plains to the present day. Eade’s series of duo solo exhibitions has been pairing artists working in different media, challenging them to unite their voices and very different styles in a connected theme. The result has been consistently rewarding, and "Footprints" is no exception.

Wilson’s raku-fired ceramic vessels might be uncovered treasures from a lost era, etched with the poppies, briar roses and kowhai that took root under a long-ago sun and continue to flourish under the blue skies that dominate McCaw’s incredible collages. In her colourful "Unfolding Land" series, Wilson combines the artistry of ceramics, sculpture, and abstracted landscape painting, creating stunning circular worlds of golden hills, craggy peaks and glistening waters, layered in three-dimensional bands of enveloping depth.

Landscapes are naturally prevalent in Central Otago art, but collage less so, and McCaw’s work — emotive, textural scenes born of scraps of recycled paper — is intricately constructed and beautiful. With hints of magazine text emerging amidst timeless scenery and historic pathways, McCaw weaves a tapestry of the old and the new, anchoring the stories of past generations in the printed words and fragmented imagery of their descendants.

By Laura Elliott