Indigenous voices were among the loudest at Cop30, the international climate conference that wound up in Brazil last week, championing the cause of the environment, their forests — and by extension, humanity.

Representing the globe’s third-largest rainforest — after the Amazon and the Congo — were West Papuans Teddy Wakum and Dina Danomira, respectively a human rights defender and indigenous activist. Prominent among their concerns, what is thought to be the largest planned deforestation on the planet — in their homeland.

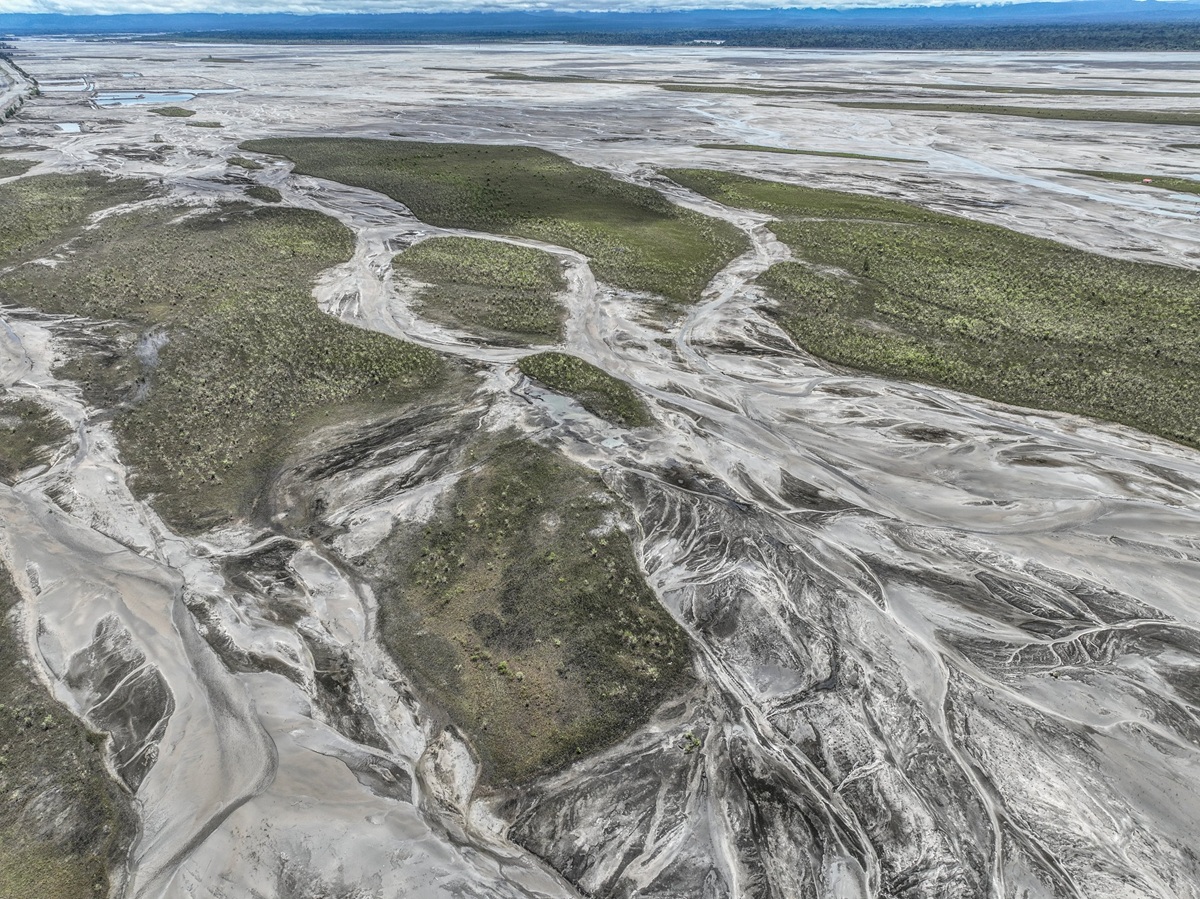

An Indonesian government "national strategic project" has begun to clear land for rice and sugar plantations, dubbed Food and Energy Estates, in the name of food security and ethanol production. In scenes reminiscent of the Avatar movies, hundreds of newly imported excavators are being deployed to do the work.

If the government follows through, up to 4.2 million ha of forest and wetlands could be felled and cleared in the south of the territory alone, according to estimates by Greenpeace.

Christchurch-based Greenpeace worker Grant Rosoman, who has long experience in the region, calls it a carbon bomb.

Indigenous spokespeople say it will destroy their communities, adding to the 100,000 people already internally displaced by conflict in West Papua. UN special rapporteurs have warned more than 50,000 indigenous people living in 40 villages will be directly affected.

A meeting in Merauke, the site of one of the proposed estates, attended by Wakum and more than 250 other indigenous representatives and local communities in March, alongside members of Indonesia’s human rights commission, demanded a complete halt to the projects "that are clearly at the expense of the people".

The Merauke project is also personal for Rosa Moiwend — about the destruction of ancestral lands. Clear-felling of the forests in the southeast of West Papua on which her people depend has begun.

Moiwend, who was recently in New Zealand for a conference, says it is done without the agreement of local people, who will not benefit. Rather, it will make a bad situation worse.

"Us in the south, it’s very much, we lost the land, we lost the source of food because our sago forest being cleared and replaced by open area," she says.

Sago palms are a particularly important traditional food source.

This is colonisation in action, she says. As far as she is concerned, Indonesia is a foreign power.

It’s a story that runs counter to the larger narratives of the second half of the 20th century, the decades of decolonisation around the globe following World War 2. West Papua is an exception to that trajectory, Moiwend says, an "unfinished decolonisation", complete with all the trademark exploitation of resources.

It didn’t have to be that way, and indeed a Dunedin man has a unique perspective on a time before all this, when other futures beckoned.

In the early 1960s writer Philip Temple joined an expedition to scale West Papua’s then-unclimbed highest peak, the 5000m Carstenz Pyramide.

His party travelled through largely uncharted territory, land occupied by its indigenous peoples for 40,000 years but shielded from outside interference by the challenging topography.

After an epic adventure, detailed by Temple in his book The Last True Explorer, his party achieved the summit and planted the flags of all those involved, including West Papua’s Morning Star, in February 1962.

"As a small symbol of hope, West Papuans should remember that their flag reached the highest point of their homeland long before the Indonesian or American," he wrote later.

At that time, there seemed every prospect that West Papua would achieve its independence, under its own flag. But then Cold War politics intervened and by the end of that same year, West Papua’s prospects had dramatically receded.

"It’s all pretty horrible, really," Temple says now of the way things played out. "I really feel for those people, because I got to know them. I travelled with groups of [indigenous] Dani people all over the place."

It seemed to him then that the locals could benefit from some technology transfer but should otherwise have been left alone.

Which is precisely what a great many West Papuans wanted.

However, Indonesians were pushing hard for independence too, and their leadership wanted Melanesian West Papua to be a part of any new state.

At the same time, the US was supporting conservative elements in the Indonesian independence movement, as a bulwark against communism, and US corporate interests were eyeing up "a treasure trove of unexploited minerals" in West Papua, as New Zealand author Maire Leadbetter writes in her book See No Evil: New Zealand’s betrayal of the people of West Papua.

As the book title implies, Leadbetter believes New Zealand abandoned West Papua during those years, as it fell into line behind Western power plays — looking away as West Papuans were railroaded into accepting Indonesian control.

The process involved an "Act of Free Choice", in 1969, which Leadbetter says involved very little choosing at all — and took place against a background of Indonesian military offensives. It is estimated as many as 30,000 West Papuans might have died to that point and more than 100,000 to the present day.

Even the US estimated there was up to 90% support for a free Papua, Leadbetter’s book records.

In some ways, not much has changed, Moiwend says. West Papuans still favour self-determination and the Indonesian military is still waging war on the people.

In other ways, things are getting worse.

"It’s like Indonesia is trying to control every aspect of West Papua from every single direction or issue. For example, because of the resources, they want to control the resources, then they send a military operation."

Indonesia argues its military operations are justified by the armed resistance of some West Papuan groups, but Moiwend says the military only makes the situation worse — worse in terms of human rights abuses, killings and the 100,000 people now internally displaced.

Radio New Zealand reported the killing of 15 civilians in the highlands last month, in an incident also said to have involved torture and rape — a report the Indonesian government dismissed as baseless.

"If we map the location of the conflict and the IDPs [internally displaced people], and we overlap it with the map of identification of the natural resources, like minerals and gas, then we could see clearly that the area that’s high intense in terms of the military operations is actually the area rich in natural resources," Moiwend says.

Of course, the Indonesian government sees things differently.

Indonesian embassy first secretary Setiadi Rachmadi says the aim of the Food and Energy Estate projects is to improve Indonesia’s capacity to provide for its people and always involves local authorities — especially when it comes to obtaining consent from tribal authorities to use traditional land.

Asked about people being displaced from their lands, he says those accusations "may come from some parties who were not satisfied with the agreed arrangements for the implementation of the projects".

"We can assure you that all processes and steps taken were lawful and always respecting the interests of local tribes."

Concerns about the exploitation of West Papua’s resources are not new. In the case of the Freeport Grasberg gold and copper mine, a huge open pit operation half-owned by the government, widespread environmental damage from tailings pollution goes back decades.

The mine is not far from the Carstensz Pyramide and the reason Temple says he no longer wants to go back, "now they destroyed the mountain environment".

The mine has regularly been the site of conflict and it seems the Indonesian government is taking no chances with its Food and Energy Estate projects. Men in uniform are everywhere in Indonesia’s own promotional material.

A press release forwarded by Rachmadi quotes the head of the Food Security Task Force, Major General of Indonesian National Defence Forces Ahmad Rizal Ramdhani, who puts the extent of the area to be planted in rice at one million hectares.

"All the projects, whether it’s a development project or national strategic project, it’s all run under co-ordination with the military," Moiwend says.

"They sent about 2000 troops, military, to Merauke, so then these military members can run plantations."

It creates a climate of fear and fuels conflict, which further displaces the population, opening access to the land and its resources for the government, she explains.

The military forces are in charge of guarding land-clearing operations and have been allegedly intimidating and silencing any opposition, the rapporteurs wrote in their report earlier this year.

A further report from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Early Warning Project warns of two plausible mass atrocity scenarios in Papua, one a result of Indonesian security forces intensifying their operations and the second involving Indonesian migrants aligning with the security forces to carry out co-ordinated violence.

This too is incorrect, Rachmadi says, insisting that Indonesia has incorporated the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination into national legislation. The government is taking affirmative action to address the root causes of Papuan issues, he says.

Under the presidency of Prabowo Subianto, the Indonesian government is strengthening engagement and co-operation with traditional communities, he says, and protecting the safety of citizens is a priority.

Military operations are a response to complaints and reports from local communities terrorised by armed criminal groups — especially in the highlands.

"Indonesian national military noted there have been numerous reports of terror acts conducted by the armed criminal group to civilians, therefore engagements were needed to protect and to ensure the safety of local communities and traditional tribes living in the region," Rachmadi says.

Speaking from Cop30, Teddy Wakum makes it clear local tribes are unbowed and that their campaigning will continue.

They see a different face to the one the Indonesian government shows to the world, he says. He and Danomira watched Indonesia’s Cop30 representatives in Brazil talk about their commitment to the environment. It’s not their experience.

"Deforestation is still going on, land grabs are still going on," Wakum says.

It had been hoped Cop30 would initiate a road map to ending deforestation globally but no agreement could be reached.

Asked how its deforestation aligned with its climate change commitments, embassy spokesman Rachmadi says all nations are faced with food security challenges.

"The national and local authorities are always working on the biodiversity conservation and forestry production to create space harmonisation models."

Asked what steps Indonesia is taking to ensure indigenous communities can continue to access traditional resources, Rachmadi says the national and local government are exploring all options to promote co-ordination and fair results acceptable to everyone, especially traditional communities.

"We are also taking notes of the concern from Indonesian Forum for the Environment ... as the largest and oldest environmental advocacy NGO in Indonesia, to try to work together to achieve better implementation of development in the region."

Various local and central government agencies are involved in "the effort to establish better enforcement of human rights in Indonesian society and civic life", he says.

Further, Indonesia is working with the regional office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on visiting the territory.

It aims to promote transparency and advance the prosperity and human rights of all its people, while acknowledging there are always measures for improvement, he says.

Meanwhile, supporters of the West Papuan cause will fly the Morning Star flag again this year on December 1 as a symbol of the indigenous community’s desire for self-determination, the same flag Temple planted on the territory’s highest peak back in 1962.

But it won’t fly in plain sight in West Papua itself, Moiwend says.

"We cannot do the flag raising because it’s too risky in West Papua. Otherwise you will end up in jail for five years at least. But people always have a way to express their political opinion through social media, other forms of symbolising the flag."

Indeed, on the livestream from Cop30, Dina Danomira wears long Morning Star earrings.

The flag will fly in Dunedin, as it has done for some years now. West Papua Action Ōtepoti co-conveners Suzanne Menzies Culling and Barbara Frame will be there.

A comprehensive partnership between the two countries through to 2029 includes military co-operation on a number of fronts, including training.

Asked what measures the New Zealand government takes to ensure the co-operation does not implicate it in the Indonesian military’s activities in West Papua, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade says the security co-operation is primarily focused on strengthening regional security, in particular around irregular migration and counterterrorism.

"This does not constitute support or endorsement of domestic security operations," the spokesperson said.

Frame is unconvinced. Despite the comprehensive partnership "encouraging human rights dialogue", Prime Minister Christopher Luxon failed to raise West Papua during a recent hour-long meeting with the Indonesian president.

"The New Zealand government does not want to acknowledge that West Papua exists," Frame says.

Moiwend hopes attention on West Papua’s situation might lead to a humanitarian pause and an end to military operations, so relief agencies can address the needs of the internally displaced population.

She’d also like to see West Papua opened to journalists and an independent fact-finding mission, something New Zealand could support through its membership of the Pacific Islands Forum, which has raised the issue in the past, she says.

Leadbetter, a champion of East Timor’s long independence struggle and a supporter of West Papuan independence, says we owe the territory that much.

"As far as I’m concerned, we have a responsibility because we were the ones back in the ’60s who turned a blind eye to Indonesia taking it over against the will of the people. And we knew that. We absolutely knew it."

It might be that revisiting support for an independent West Papua is now in the interests of all humanity.

Success stories possible despite pressures

In one example, the Knasaimos-Tehit community, in the southwest of the territory, has managed to prevent government settlement schemes, illegal logging of their forests and plans for palm oil plantations. Now, working with NGOs and Greenpeace, they’ve achieved legal recognition of their territorial rights from the local government and are pursuing a "customary forest" permit for all 97,411ha of their tribal lands, according to Greenpeace’s Forest Solutions report, published last month.

Tribal leader Arkilaus Kladit is quoted in the report talking about the profound connection they have to the land.

"The forest is a precious gift that has been passed down to us through generations, an asset that sustains our way of life. We are dedicated to preserving it, as it holds everything we need," he says.

"We are committed to educate and motivate everyone to understand the irreplaceable nature of our land and forest and that we cannot buy and sell it."

The recognition the community has won has allowed it to establish sustainable enterprises, including the production of sago flour and banana chips.

It’s a showcase to inspire other communities to do similar things, Rosoman says — to manage their land themselves, rather than see it used for industrial-scale logging or palm oil operations.

It’s quite a clash of paradigms, he says, and confronts the question of who benefits from development.

"If you look at the food estate development, it’s supposedly developing food from a national food security point of view for Indonesia as a whole, even though most of it’s going to energy. For example, they’re producing sugar cane for ethanol.

"So, that’s the narrative that’s used by the government. But what it’s doing is it’s starving the local people. It’s destroying all their food sources, which are found in those forests and wetland areas."

Flag raising

• West Papua’s Morning Star flag will be raised in the Octagon on Monday at 5pm.