He was notorious for telling tall tales. So who, really, was Otago’s first harbour pilot, Richard Driver?

Bruce Munro talks to two of Driver’s descendants, whose years of research bring to life a colourful character — one who helped birth Dunedin while bridging the region’s Māori and Pākehā worlds.

Julia Monaghan’s first big breakthrough came in Tasmania.

Since her childhood in Dunedin, raised by her grandmother, Monaghan had heard stories about her larger-than-life forebear Richard Driver. But how many of the stories of his adventurous life, passed down from the man himself (an acknowledged teller of tall tales), could be believed?

Monaghan had been researching Driver’s life for several years when she visited Hobart’s downtown records archive. There, to her delight, she found "Richard Driver, apprentice" listed among crew aboard the convict transport ship Governor Ready when it departed for Sydney, on August 21, 1827.

"This was probably my turning point in believing him," Monaghan recalls.

"It was exciting and satisfying to finally find new evidence that none of his descendants had known about ... and really energised me to continue searching for records about him, both inside and outside New Zealand."

Harbour pilots played a vital role in the early days of the European colonisation of Aotearoa New Zealand. Water was highway, train track and flightpath. So settlements were most often built around harbours, whose seaports were the airports, train stations and carparks of their day.

For that reason, the fortunes of a new community rose or fell on the quality of its harbour pilot. Ships’ captains would visit or avoid a settlement depending on the ability and reputation of its pilot to expertly bring vessel, crew, passengers and cargo safely from open sea to anchor.

Richard Driver was the first official pilot for the Port of Otago, gateway to the nascent Free Church of Scotland settlement, Dunedin. Despite years of planning, the willingness of settlers to traverse the globe and the goodwill of local Māori, the fledgling township would wither and die if, through lack of a suitable pilot, it could not attract ships.

Driver was the capable pilot the new settlement needed; his fame and Dunedin grew together.

Driver’s reputation was not just as an expert pilot; he was also a big man with a big personality and big stories to tell.

By the time Monaghan was growing up, the stories she heard of her great-great-great-grandfather, repeated by both Māori and Pākehā branches of the family, depicted Driver as "a bit of a god-like figure".

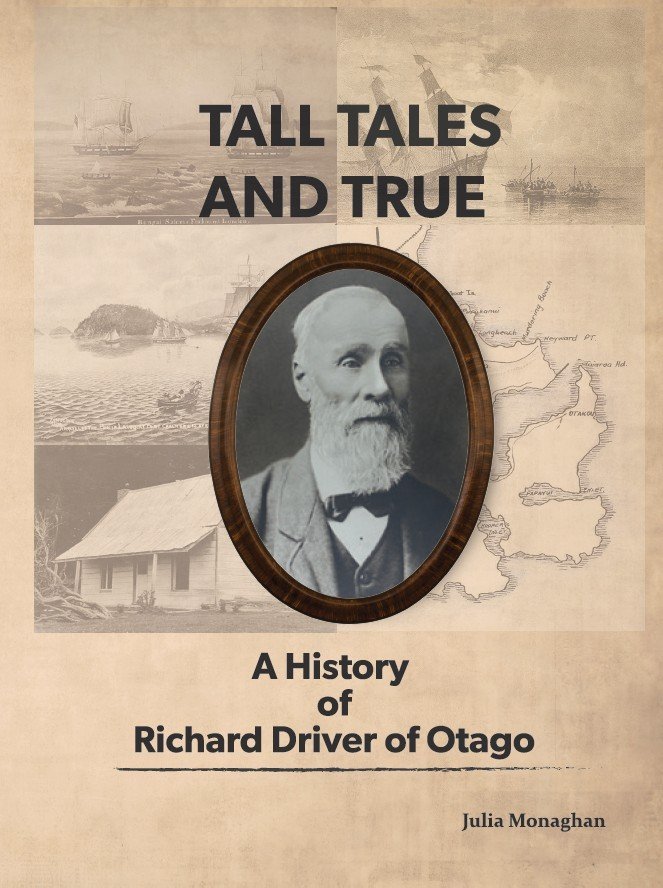

It was the need to know more clearly who Driver was that drove Monaghan to research and self-publish Tall Tales and True: A History of Richard Driver of Otago.

Identifying the correct Richard Driver, of Bristol, England, was one task. He was, Monaghan says, the son born in 1812, to Elizabeth Driver and her cabinetmaker husband Matthew. While the boy’s brother Frederick became an ironmonger and his sister Emma a music teacher, Driver, who may have run away to sea as young as 12, was most likely apprenticed at the age of 14 to Captain John Young, master of Governor Ready.

His name on the crew list two years prior, and the fact he would still have been serving his five-year apprenticeship, lends credence to the shipwreck tale, Monaghan says.

She adds that an account of the shipwreck mentioning "thoughtless youngsters" who amused themselves and had to be "reminded of their duty" sounds like the antics of her high-spirited forefather.

Over the next decade, Driver might have returned briefly to visit family in England, probably went to the United States (US) to seek work from relations and then crewed whaling ships that likely hunted whales in New Zealand waters.

In November, 1838, Driver was listed as crew of US whaler John & Edward. On that list, he is described as a resident of New London, Connecticut, US; aged 25; 6 foot 1 inch tall; with a light complexion and dark hair. By this time, he also seems to have risen from seaman to mate — a sign he had become a skilled sailor.

John & Edward reached Otago in May 1839. But when the ship left a few days later, Driver did not sail with it. Instead, he stayed with Māori at Pūrākaunui, on the coast north of Otago Harbour, and took the local chief’s daughter Motoitoi as his wife.

One of the family’s stories says Motoitoi threw her kahu kiwi (kiwi feather cloak) over the stranger when he came ashore, saving him from being killed by her relatives. That cloak and a greenstone mere were believed to be held by a descendant living in Wellington, but what became of them is not known.

Another mystery was the circumstances in which Driver left his ship; some family thinking he left without permission, others saying he was too honourable for that.

Monaghan discovered the definitive answer when visiting the offices of Connecticut’s New London County Historical Society. There, in the records of John & Edward, written against Driver’s name, was one word, "Deserted".

Monaghan, who went to Otago Girls’ High School, lives with her husband in Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia. She has worked around the world as a midwife and as a midwifery lecturer and researcher.

Researching Driver’s life has been a challenging, collaborative effort, she says.

In addition to herself, much of the detective work in recent years has been by Driver descendants Stan and Alison Durry. Writing the book, she has had help from another extended family member, archaeologist and historian Joan Miro Lawrence, who grew up on the Driver family farm at Long Beach, north of Dunedin.

Lawrence says the main challenge has been trying to tease reality from myth.

"The longer we researched, we realised that most of his ‘tall stories’ were actually true," she says.

The deserter and his Māori wife appear to have lived in a beach cave at either Whareakeake or Kaikai, neighbouring beaches southeast of Long Beach, and then in a more substantial home.

The couple had three daughters, Maria, known as Maraea; Mary, known as Mere; and Emma.

In August, 1846, Motoitoi, aged about 21, died, perhaps of tuberculosis.

A year later, Driver and Mere Poroki, possibly Motoitoi’s sister, had a son John, known as Jack. Mere died that same year.

During those years, Driver had been freelancing as Otago’s harbour pilot, competing with a couple of other local sailors to be commissioned to guide visiting vessels to safe moorings.

In 1848, the role was formalised — and Driver was made Port of Otago’s first official harbour pilot.

It was Driver who piloted John Wickliffe and Philip Laing — Dunedin’s founding settler ships — safely across the entrance bar and up the harbour to Port Chalmers.

Fifty years later, in the Otago Daily Times’ Otago Settlement Jubilee Supplement, Driver was remembered as "a most plucky and daring man, unsurpassed in skilful seamanship who, with a bar harbour and no tug, handled every vessel successfully, without a single accident, thus keeping a good name for the harbour and greatly helping the prosperity of the place".

Also on display when the future city’s first settlers arrived were Driver’s personality and sense of humour.

Knowing he was the first local settlers would meet, Driver drew alongside Philip Laing in a whaleboat probably crewed by his Māori relatives, climbed aboard and told the immigrants the "cannibals" were selecting "the best of you for the next feast".

Lawrence says Driver had a large, charismatic personality, attracting admirers and detractors in equal number.

"He had a great sense of humour and loved to tease," Lawrence says.

He is recorded telling immigrants if they walked 7km up steep Flagstaff hill they could catch a non-existent omnibus back to town.

He also caused problems by telling newcomers a local settler’s pigs were free for the taking.

His outrageous tales become known as "Driver’s stories"; so little believed that when he passed on news from a passing ship that the Crimean War had spread to include fighting between English and Russian soldiers, the Otago Witness, of February 4, 1854, chastised Driver for his "well known predilection ... for what is vulgarly called chaffing".

At the same time, Lawrence says, her great grandfather was "highly accomplished in everything he turned his hand to", although, she adds, he "was not backward in letting people know his abilities".

Among the immigrants on Philip Laing when it arrived, in 1848, was 17-year-old Elizabeth Robertson who, a year later, married 36-year-old Driver.

For a dozen years, Driver served as harbour pilot, helping the four-fold growth of Dunedin to a settlement of 2000 citizens.

In 1860, he resigned and moved his family to 80 acres of land he had bought at Pūrākaunui, near where he had first come ashore 21 years earlier.

Four years later, he was granted a further 114 acres.

He and Elizabeth had another eight children, they farmed dairy cows and sheep, Driver indulged his love of horses, got involved in local politics and advocated for local Māori, earning him the label, "Pūrākaunui Māori’s white man".

On January 19, 1897, aged 84 and still on his farm, Driver died of a cerebral haemorrhage.

Flags were flown at half-mast on the harbourmaster’s office and on vessels at the wharves.

Elizabeth died four months later, aged 65, survived by 11 children, 74 grandchildren and about 50 great-grandchildren.

Driver’s descendants, Māori and Pākehā families, stayed on and around the family farm for several generations. Those who scattered throughout the lower South Island included his and Motoitoi’s daughter Emma’s descendants from her marriage to John Tregerthen, some of whom changed their name to Tirikatene and have produced three members of Parliament representing the Southern Māori, now Te Tai Tonga, electorate.

Some questions about Driver remain unanswered, Monaghan says.

Key among them, she would like to know whether he ever returned to visit family in Bristol before settling in New Zealand.

"One of our hopes is that this publication will prompt others to share and investigate more of our history."

All the hours spent chasing records of baptisms, marriages, wills, dates and connections scattered around the globe have given Monaghan a clearer view of her renowned, but not flawless, ancestor and a stronger sense his enduring contribution.

"His greatest legacies are probably the safe arrival of many of the immigrant ships and their passengers to Otago as well as the numerous descendants, both Māori and European, that bridge the gap between the original occupants and the new arrivals."

• Tall Tales and True: A History of Richard Driver of Otago, by Julia Monaghan, self-published on lulu.com, 2024, RRP$24.07. On request, a free, electronic PDF copy is available by emailing OSM.Collections@dcc.govt.nz or julia.monaghan222@gmail.com