Dunedin women were prominent among those honoured by Belgium following World War 1, and the European country has not forgotten, writes Toitu Otago Settlers Museum curator Sean Brosnahan.

Since late September several hundred white crosses have dotted Queens Gardens in central Dunedin. Each cross represents an Otago soldier who lost his life during 1916.

A similar display was mounted last year for the men who died in 1915, and will be again in 1917 and 1918.

The crosses offer a powerful reminder of the terrible losses suffered in Otago as a result of World War 1.

Most of the attention of World War 1 commemorations to date have concentrated on the men who fought and died.

This seems entirely fitting.

After all, an estimated 20,000 or more Otago men served overseas during the war.

Almost 2000 from Dunedin alone were killed.

Next year, however, Toitu Otago Settlers Museum is planning to switch focus and commemorate the war from a female perspective.

THE BELGIAN CONNECTION

The idea for such an exhibition was initially prompted by a recent appeal for assistance from the Belgian Government. Support for "poor little Belgium" was a big part of patriotic activity in Dunedin from 1914-1918.

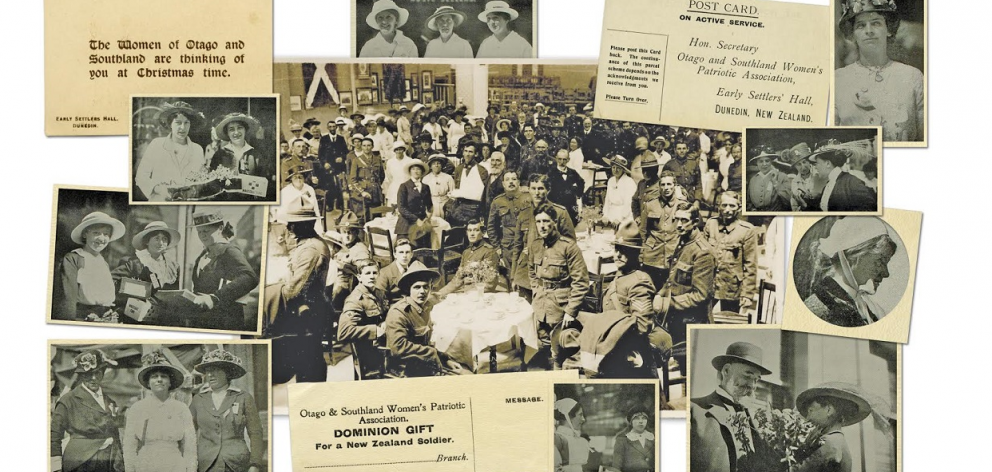

Most of the activity was organised and carried out by women, working through organisations such as the Otago and Southland Women’s Patriotic Association (OSWPA).

Thousands of pounds were raised and hundreds of tonnes of relief supplies gathered up and dispatched to Belgium.

In grateful acknowledgement, the Belgian Government created a special medal, the Médaille de la Reine Elisabeth (Queen Elisabeth Medal). Thirty-one of these medals were presented to women in New Zealand and 24 of the recipients were from Dunedin.

Now, a century on, the Belgian Government is planning to honour the graves of the Elisabeth Medal recipients.

Each grave will be repaired as necessary and then marked with a commemorative medallion.

At the same time, Belgian diplomatic representatives would like to make contact with descendants of Dunedin’s medallists so family can be involved in the restoration process and share in their forebears’ special connection with the Belgian state.

A representative of the Belgian Government is likely to visit Dunedin in late 2017 to formally commemorate the Elisabeth medallists as part of the centennial of the battle of Passchendaele.

SERVICE AT HOME AND ABROAD

The Otago and Southland Women’s Patriotic Association, led by the redoubtable Miss Jean Burt, was among the most successful patriotic organisations in New Zealand.

From its base in the Early Settlers Hall (now part of Toitu), it co-ordinated legions of women who baked, knitted and sewed, entertained soldiers, or raised funds in all sorts of ways.

Enormous sums were raised and donations passed on to relief funds in Belgium, Britain and Italy.

"Comfort packs" were assembled for Otago troops and dispatched to the front line with messages of support from home.

Maori women also played their part, sending muttonbirds, for instance, to members of the Maori Pioneer Battalion.

Members of the Red Cross also undertook many tasks to support soldiers at home and overseas or provide assistance to war refugees.

The president of the Dunedin Red Cross branch, Miss Frances Rattray, was one of those women recognised by the Belgian Queen for her efforts (or was it one of her sisters?).

Red Cross volunteer Dora Skinner played her part by visiting soldiers in Dunedin Hospital, including some of the men who had been ostracised after being sent back to New Zealand with venereal disease.

Such men faced an otherwise lonely existence, kept in isolation on Quarantine Island in Otago Harbour.

One truly remarkable contribution to the war effort was made by a Dunedin woman who spent six years developing an improved life-jacket after the wreck of the Titanic.

Mrs Orpheus Beaumont won a competition organised by the British Board of Trade with her design of a canvas kapok-filled jacket that could support 15 times its weight in water.

The Royal Navy ordered 30,000 of her "Salvus" life-jackets in early 1918.

The "Salvus" became the standard life-jacket and saved thousands of lives until it was superseded by synthetic foam jackets in World War 2.

Patriotic activity was not the only way Otago women played their part in the war.

Museum intern Katherine Neville-Lamb has been tracing a diverse range of war experiences of local women, at home and abroad.

Some of those identified were part of the official armed services.

More than 130 Dunedin-trained nurses and masseuses, for example, went overseas as members of the New Zealand Army Nursing Service (NZANS).

Dunedin-born or trained nurses Lorna Rattray, Catherine Fox and Mary Rae were killed when the troopship Marquette was sunk in October 1915, while transporting No1 New Zealand Stationary Hospital to Salonika.

Otago’s pioneering female medical graduates also played their part in the war.

The first female doctor in New Zealand, Dr Emily Siedeberg, offered her services to the military on the outbreak of war, notwithstanding her German father and German surname (which drew some unwarranted criticism at the time). She spent a year in a British hospital at Sheffield, treating the wounded.

Her friend, Dr Margaret Cruickshank, meanwhile, who had been New Zealand’s second female medical graduate, took a different route.

She held the fort as a GP in Waimate while her male colleagues went to war.

Dr Cruickshank eventually gave her life, struck down while combating the influenza pandemic at war’s end.

She is remembered today by a statue in central Waimate.

The NZANS was the only arm of the official New Zealand military establishment that accepted women.

But a number of quasi-official groups were formed, such as the Volunteer Sisterhood organised by Ettie Rout.

Ettie achieved notoriety later in the war for her work promoting "safe sex" options to New Zealand soldiers.

The only southern recruit to the Volunteer Sisterhood does not seem to have been part of that programme (disavowed by many of the Sisterhood).

This was Georgina Jopp from Alexandra and Dunedin. Jopp ran canteens for New Zealand soldiers in Egypt through the war.

While most of the active servicewomen were young, middle-aged Harriet Simeon from Dunedin had one of the more diverse war careers.

After following her soldier husband overseas early in the war, Mrs Simeon served as a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse for three years at military hospitals in Egypt, Britain and France.

She then switched tack in 1918 and joined the newly formed Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF). By war’s end she held rank as a deputy assistant commodore.

Stewart Island-born Madeline Rankin also joined the WRAF.

The 20-year-old served as a motorcycle dispatch rider in England.

Other Otago women followed sons or husbands overseas and "did their bit" for the war effort in Britain.

Elizabeth Stewart, for example, served as a VAD nurse and proudly wore the badge of the 12th Otago Mounted Rifles on her uniform.

The badge had been designed by her late husband, George, whom she had nursed at Alexandria after he contracted a fatal illness while serving with the OMR at Gallipoli.

Mrs Stewart and her sister Agnes Herbert then moved on to England and both earned an MBE (military section) for their nursing work at the No1 NZ General Hospital at Brockenhurst.

In London the New Zealand High Commissioner, Sir Thomas Mackenzie (from Dunedin), headed a very active New Zealand War Contingent Association (WCA).

Much of its work was done by the well-to-do ladies on its Women’s Committee.

These included many Dunedin women living in England. Mackenzie’s daughter Helen was its secretary and she was supported by a posse of influential former Dunedin residents: Lady Mills, Mrs Mackenzie, Miss Reynolds, Mrs Aufrere-Fenwick, Miss Constance Williams, Mrs Alfred Bell, from Shag Valley, Mrs Wolf Harris and Mrs John Macfarlane Ritchie.

Mrs Ritchie may have been typical: a wealthy widow with three sons fighting with imperial regiments, she set up camp in England with her daughter Mary for the war’s duration.

The WCA founded, equipped and supported hospitals, convalescent homes, and canteens for wounded New Zealand soldiers across Britain.

The association’s lady visitors personally called on every wounded New Zealander, wrote letters home on their behalf and made sure they received extra comforts during their recuperation.

They also established a NZEF Residential Club in the heart of London for New Zealand soldiers on leave and made sure that the colonials were generously treated by their friends in the British establishment.

Free tickets to theatres and other shows, and weekend stays at British country houses were all part of the association’s programme.

They even established a home for New Zealand nurses to rest and recuperate on the English coast.

THE DISSENTERS

Although patriotic support for the war effort was fairly general in Otago, there were also those who stood out against the war.

In Dunedin, Miss Mary McCarthy was a fervent socialist and peace activist.

She and Lilian Rundle headed a local branch of the Women’s International League, standing against the tide of pro-war feeling.

One of their initiatives was to bring Adela Pankhurst, a member of the famous English family of suffragettes and a trenchant critic of conscription, to Dunedin.

Hundreds turned up to hear their advertised lecture but unfortunately Miss Pankhurst didn’t turn up. She went to the West Coast, instead.

Mary McCarthy, meanwhile, was secretly supporting her brother Arthur, who had gone "underground" to avoid military service.

There were many similar cases, especially among socialists, pacifists and Irish objectors.

Men with these convictions often hid out in remote areas, or under assumed names, to evade a call-up. In many cases, their wives, sisters and mothers offered crucial support in their clandestine lives.

Other women, such as Mary Baxter, of Brighton, or Mary Cody, of Riversdale, suffered years of anxiety for lack of information on where their sons were.

Seized by the military authorities, five Baxters and three Codys were serving harsh prison sentences in New Zealand or overseas.

THE WAR STORIES OUR GRANDMOTHERS NEVER TOLD US

These women’s stories of war are much less well known than they should be.

Often that is because the evidence of their activities has been lost or is poorly represented in archives and museum collections.

That is why Toitu is sending out the call for help from ODT readers.

Do you have information, photographs, or artefacts that would help us tell the "war stories our grandmothers never told us?".

Is there an old nurse’s uniform or VAD cape in the attic?

Maybe some of the comfort packs, "housewives" scarves or balaclavas put together by the OSWPA came back with a soldier to your family.

If so, the museum would love to hear from you.

Mary Stewart in 1915. Photo: supplied

Mary Stewart in 1915. Photo: supplied

WHY SO MANY FROM DUNEDIN?

George Denniston was Belgium’s honorary consul in Dunedin during World War 1.

When asked to recommend recipients for the new medal he provided 24 names, including that of his daughter Eleanor.

All of Denniston’s recommendations were accepted and medals awarded.

Belgium’s consuls in other parts of New Zealand seem to have been more circumspect in offering names.

Dunedin’s Elisabeth medallists will be a central focus of Toitu’s new exhibition.

Working with the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, all of the women have been identified and the burial places of those who died in Dunedin have also been located.

HERE ARE THEIR NAMES

Barningham, Ellen Mrs Blackman, Mary Seward Mrs Burt, Jane Alexander (Jean) Miss Callan, Margaret Elizabeth Mrs Cook, Jesse Guild Mrs Cunninghame, Annie Mrs Denniston, Eleanor Fairre Miss Fenwick, Edith Louisa Elizabeth Mrs Ferguson, Mary Emmerline LadyGeerin, Kathleen MissHayward, Laura Maria MrsHercus, Jane Kerr Chalmers MissHutchison, Anna Pearson Lady Jackson, Margaret Ann Mrs Melville, Catherine Smith Mrs Morrison, Barbara MrsMorice, Agnes McKinnon Mrs North, Emily Mrs Park, Annie Penelope Mrs Pinfold, Elizabeth Mrs Rattray, Miss [Was it Ada, Frances or Katherine?] Runciman, Jane Elizabeth Miss Stewart, Mary Downie Miss Wilkinson, Laura Mrs.

BELGIUM CALLING

The Belgian Government would be keen to hear from family of any of these women.

Please get in touch in the first instance through Sean Brosnahan at Toitu Otago Settlers Museum.

Email: Sean.Brosnahan@dcc.govt.nz.