Do you think what you do doesn’t amount to much? Maureen Howard finds out why it is worth the effort to reduce our personal greenhouse gas emissions.

On bright winter days in Geraldine, a warm breeze wafts through the house from the "solar air heater'' fitted to the north side of Rhys Taylor's passive-solar, high-thermal-mass home. Then there's the radiant heat gained by the dwelling's passive solar design, a woodburner that uses homegrown replanted timber, high thermal mass flooring and walls, insulation that exceeds the building code, and solar electric panels that often generate excess energy to return to the grid. It all makes for an energy-efficient and comfortable home.

Taylor and his partner, Anne Griffiths, finished building their South Canterbury home in 2008 on their 6ha lifestyle block that includes a native forest under QEII covenant, vegetable patches, a hen run and fruit trees. Constructing their one-bedroom home from scratch meant they could build in efficiencies.

"However, there's always a sting,'' he adds, referring to the cement they used to construct their home for its high thermal mass properties. Cement production carries a heavy carbon footprint, so the couple have built their house small, just 90 sq m, and used a cement product mixed with ground-granulated blast-furnace slag, a waste product from the steel-making industry. An extension is planned.

It all means Taylor is well placed to reduce his carbon footprint at home. But there are any number of opportunities beyond the front gate.

Come rain or shine, Prof Niki Harre cycles the 16km round trip from her weatherboard home, along the flats of suburban west Auckland, to her workplace in the school of psychology at the University of Auckland.

"I almost never use the car during the week,'' she says.

Author of Psychology for a Better world, Harre is bucking the trend of the academic lifestyle. As high achievers, academics are generally "high emitters'' when it comes to travel. However, so far this year, Harre recollects just one or two flights, both domestic.

Instead, these days she increasingly makes use of video-conferencing opportunities. Earlier in the year, instead of going to a conference in Chicago, she attended from home.

"I was involved in three sessions, which were at 2am, 4am and 6am New Zealand time. It was challenging to get up in the middle of the night but much better than flying all that way.''

At the age of 13, Jamieson adopted a vegetarian diet for ethical reasons and realised after reading Diet for a Small Planet, by Frances Moore Lappe, that "eating food is also a political act, because less land is needed to produce vegetarian food than to produce meat''.

For health and environmental reasons she now eats 95% organic food when at home, buys locally grown food where she can and chooses less processed foods.

"I'm very much a label watcher, choosing GE-free and organic food,'' she says.

Creating food waste is relatively rare in her house; but she has a variety of composting options available via her hens, an outdoor compost bin and a bokashi bucket. Growing up, her mum modelled waste-free habits.

"She'd make some dish and she'd say `Now guess what the secret ingredient is?', and it would be leftover porridge or something!'' Philippa says, laughing.

Sustained by a relatively modest income, Jamieson has prioritised her food purchases over many other expenditures.

"I'm not a big consumer, I don't buy much stuff,'' she says.

She has also cut her electricity bills by turning off her hot water cylinder during the week and showering after her daily swim at the local pool.

When it comes to carbon, money matters. Regardless of country, it is the richest 10% of the world's population who are responsible for emitting about 50% of the carbon emissions that come from personal consumption and personal choices, according to a 2015 Oxfam report.

Although being in a high-decile bracket is associated with emitting more CO2 per dollar spent, it is the sum of money spent that is the greatest predictor of the size of a carbon footprint, according to research by Motu.

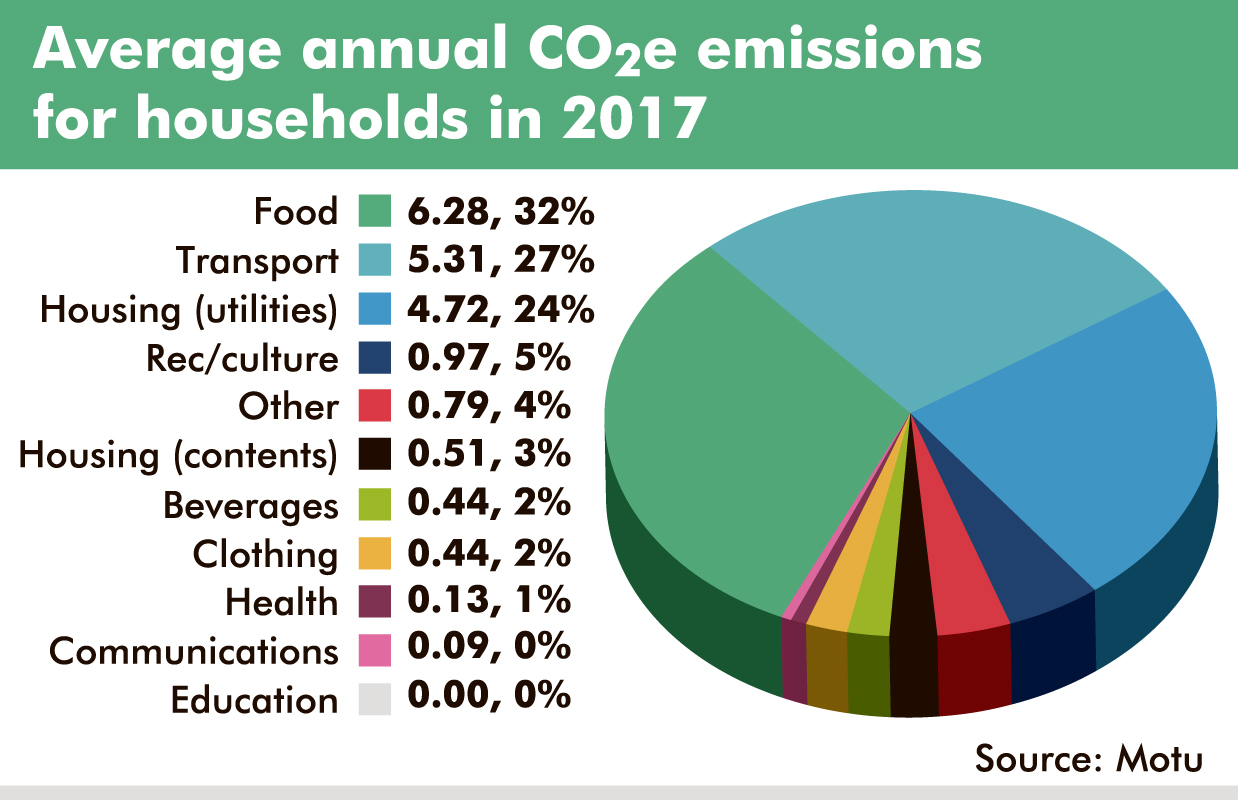

Using product consumption data from the 2007 Household Economic Survey, the independent think-tank based in Wellington has calculated the average New Zealander emits 9.93 tonnes of CO2e per year.

Breaking it down, the three biggest sources of personal carbon emissions come from what we eat (32%), in particular meat and dairy; how we travel (27%), in particular fuel use for the car; and our utility bills (24%), in particular electricity consumption.

However, averages hide New Zealanders' myriad lifestyles and the steps that can reduce personal carbon footprints.

In terms of food, reducing protein intake overall and replacing animal proteins with plant-based ones reduces our carbon footprint, according to the comprehensive 2019 EAT-Lancet report.

Jamieson adds that it is important to find out where those plant proteins are coming from and how they are produced.

"I avoid GE soy for environmental reasons, including that some of it has supplanted Amazon rainforest.''

After growing what we can ourselves, sustainable food advocates suggest we shop at farmers markets. This isn't so much about food miles, which are only about 10% of the total footprint.

Rather, the aim is to support those using lower-carbon farming practices that reduce soil carbon loss and increase soil carbon sequestration, use less fossil fuel-powered machinery, less synthetic fertiliser and maximise food production per hectare. Small organic, permaculture, regenerative and biological farming all employ practices that can help the transition to smaller-footprint biodiversity-friendly food production, they say.

Personal travel options begin by asking whether we need to travel in the first place, Taylor says.

He suggests people consider working part-time from home or living closer to their workplace.

"If you do travel by car, combine your car trips so they achieve several purposes, and for close to home use a bike.''

Developing a multi-modal lifestyle of walking, cycling and public travel may mean a household can give up a vehicle.

Flying has the biggest carbon kick, even more than driving the same distance on your own. But in particular, a single international trip can double annual emissions. A return flight from Christchurch to London, for example, emits about eight tonnes of CO2e.

A novel option for someone with a bit of time up their sleeve, is freighter ships. They take paying passengers from New Zealand to Hong Kong and from Australia to Singapore, as well as across the Atlantic, according to travel agent Hamish Jamieson, of Freighter Travel NZ.

The carbon emissions associated with travelling by freighter ship are much smaller than those from travel by aeroplane or cruise ship on a per passenger per kilometre basis, according to travel research conducted by Dr Inga Smith and her team at the University of Otago.

Closer to home, the buildings we live in provide opportunities.

"We often have buildings that are artificially overcooled in summer and artificially overheated in winter,'' says Taylor, whose solutions range from new builds with passive solar design to retrofitting with low-emission-coated secondary glazing.

But every molecule of fossilised carbon released to the atmosphere affects our planet, and more than we think. The melting glaciers we read about today are a consequence of greenhouse gases already emitted. Climate scientists from the Universities of Bremen and Innsbruck calculate that 1kg of CO2 amounts to 15kg of future glacier ice melt. That's equivalent to a 7.5km drive in the average family's petrol car.

Prof Brenda Vale, of Victoria University of Wellington and co-author of Time to Eat the Dog and Everyday Lifestyles and Sustainability, says everyday actions add up across a lifetime to many carbon tonnes.

"You can make a really big difference just by changing what you do and what you choose to do and I think that was what we were trying to show in both of these books,'' she says.

Personal actions also matter for reasons that ripple beyond the immediate measures of their gaseous emissions. Those personal choices also inform the way we engage politically.

"I think it's really important to take personal action so you yourself learn about the context and become able to contribute to those public conversations,'' Prof Harre says. "Until you try and take personal action on it you don't fully understand the phenomena.''

Research shows that walking the talk helps. Advising others to reduce their meat intake while dining daily yourself, is not a convincing look.

"It won't feel right to you and it won't feel right to the people that you are talking about it with,'' says Harre, who cooks only vegan food herself but is flexitarian about eating the food cooked for her by family and friends.

Our actions start to change naturally as we engage with the issues, Harre says.

"We develop a sense of what feels right and what doesn't.''

For example, she almost never drives her car for a short errand and when she does, it jars.

"I feel slightly ill and disoriented, as if my world is not as it should be.''

As the planet's most imitative ape, our actions are also thoroughly contagious.

"You can't underestimate that because almost everything that I have learned to do I haven't figured out myself, I've copied it off other people.''

Even when we think we are being terribly original, we are largely copying.

"Ultimately, progress happens by copying with slight alterations,'' Harre says.

Lastly, for the less politically inclined, Harre says, taking personal action is an avenue by which people can quietly live out their beliefs.

"So we might prefer to be vegan, buy second-hand clothes, not travel overseas by air, whatever it is, than to try to convert other people. That's a contribution too,'' she says.

For Taylor, whose work involves helping his community shift to a low-carbon footing, the personal overlaps with the public.

"The cumulative effects of what I am doing are taking me gradually down towards my fair world share, rather than being three or four times larger than it. So it is worth doing and I need to live with myself. I don't like being conflicted all the time between what I believe and what I'm still doing, such as booking a long-haul air flight to visit my mum in the UK. Flights are occasional, mostly we chat via Skype each week, which is virtual travel.''

The sacrifice should not be too personally excessive, Harre says.

"I think if there is something that nourishes you and keeps you going, and you know that it's bad for the environment, but it would make you really unhappy and feel deprived to give it up, then I don't think you should give it up.''

But that can also change.

"If you try to keep connected with the issues, you might find after a time that [environmentally unfriendly] thing isn't so appealing,'' Harre adds.

Prof Vale believes that it's up to us to lead the way. There is no time to wait for government action. The longer we take to halt climate change the harder it will be. "It's taken the Government a long time to come out and say no plastic bags. If we wait for the legislation it will be too late,'' Vale says.

"As an individual you can also join with others to make political change. For example, setting up a sustainability committee at work and investigating sustainable procurement options, making submissions to local authorities on climate actions, joining a group focused on regenerating natural landscapes,'' Harre says.

For more

If you would like to learn more about what you can do to reduce your carbon footprint:

• The Sustainable Living programme offers future living skills for eco-friendly low-carbon living through participating councils.