The need for New Zealand to look after the health and wellbeing of its past Olympians is set to be underlined by a University of Otago study involving former elite athletes.

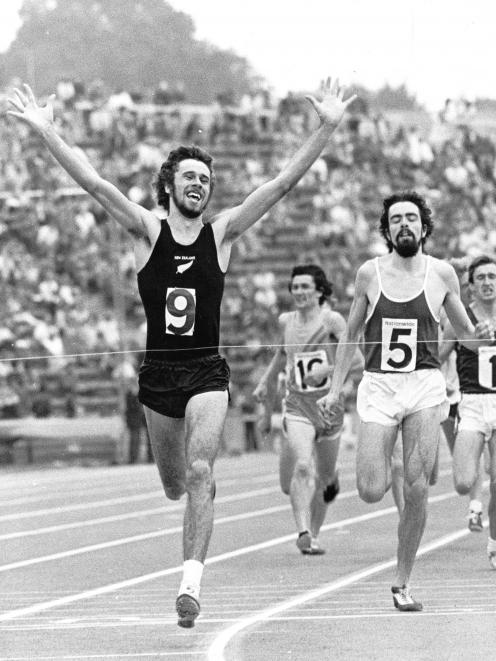

Principal investigator Dr Xaviour Walker said conversations with 1972 New Zealand Olympic medallist and New York Marathon winner Rod Dixon helped him to see that no-one was monitoring the health of former high-performance athletes, or ex-Olympians, ‘‘and that we needed to do something about this’’.

‘‘These high performance athletes, we need to look after them,’’ Dr Walker said.

‘‘They serve our country, they train for 10, 20 years and then we as a country take a lot of pride in what they do.

‘‘We also have to look after them, they really are a national treasure that we have to care for, these athletes — provide them support.’’

The launch of the study this week had been a year in the making, Dr Walker said. But he and others involved in the study were sensitive about the timing, as the athletic community and others mourned former Olympic cyclist Olivia Podmore, who died unexpectedly on Monday.

Essentially, over the coming months, as athletes returned from the Tokyo Olympics, researchers wanted hundreds of current and former Olympic, Paralympic, and Commonwealth Games athletes to take part in a comprehensive 40-minute online survey covering the health status, physical activity, nutrition, and mental health of athletes.

Athletes would also be asked about their nutrition and exercise during the year they last competed in the Olympics, Paralympics, or Commonwealth Games. International research has shown that Olympic athletes live longer than average, and have less age-related muscle loss.But research also suggests an increased risk of some health conditions, including heart arrhythmias.

Dr Walker said the study would involve an in-depth look at Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), a serious illness caused by a mismatch between energy intake from diet and the energy used by athletes in exercise.

But the survey would help to identify further areas of study.

Athletes were finely tuned human beings, but at times they pushed themselves right to their physical limits, Mr Dixon said. He had seen heart issues plague some of the world’s best runners.

Crucially, at Massachusetts General Hospital, which cared for Boston Marathon runners, a doctor told him that someone with his past could run on a treadmill for an hour and a general check-up would not find anything wrong with his heart.

But specialists detected a slight scarring ‘‘in its infancy’’ that could have led to complications if left untreated.

‘‘In my arena, I just had to beat the next guy, and I was determined, and I don’t know where I took my body,’’ Mr Dixon said.

‘‘The determination and the power of the mind was overpowering anything else.

’’University of Otago department of medicine Emeritus Prof David Gerrard is an ex-officio member of the research team.He was a semifinalist at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and won gold and bronze medals at the 1966 Kingston Commonwealth Games.

He said yesterday he hoped to make ‘‘a little contribution’’ to understanding whether sport carried a positive legacy.He wanted to know that the physical effort and the regimented lifestyle he had led as a young man had a benefit in later life. And for the most part, he believed it did.

Many of the health issues athletes faced were faced by the general population as well, but athletes had the benefit of a good diet and lifelong exercise habitats that bolstered their chances against illness, he said.