After months of painstaking reconstruction, modern science has finally revealed the face of Otago Museum's 2400-year-old Egyptian mummy.

The mummy's reconstructed head went on display alongside its casket at the museum on Thursday.

The mummy, which has resided in the People of the World gallery since it was bought for the museum by Bendix Hallenstein in 1894, is believed to have come from the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes.

While the identity of the mummy is unknown, it is believed to be that of a woman who lived about 2400 years ago, was in poor health, and died aged about 50 years.

Otago Museum commissioned Dr Louisa Baillie, a researcher in forensic facial approximation in the University of Otago's department of anatomy, and a team of fellow scientists to reconstruct the mummy's head and facial features based on radiology images taken in 2000.

The three-month project involved studying the woman's physical health, ethnicity and likely age at time of death.

"We discovered that she was about 50 years old, and that she had only a few teeth and terrible abscesses in her mouth,'' Dr Baillie said.

The woman also had arthritis, scoliosis of the spine, and otosclerosis (bone growth in the inner ear).

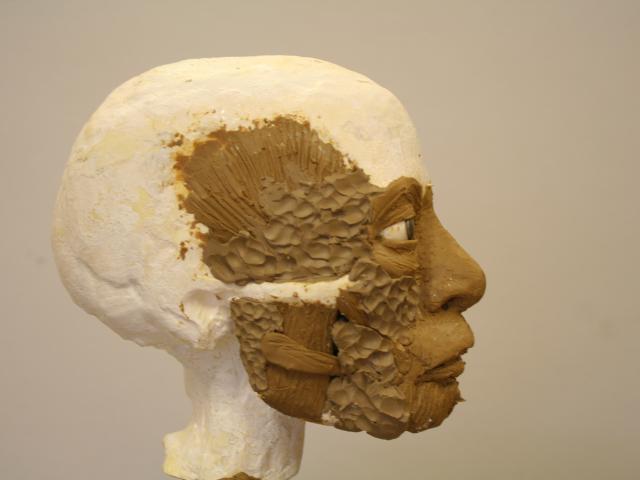

Medical imaging software refined the 17-year-old CT scans and X-rays to provide detailed views of the skull and facial bones and accurate measurements for a 3-D polyurethane copy of the skull.

This has allowed a more accurate reconstruction of the woman's face than was achieved in 2008.

Markers to guide soft tissue depth were placed on the 3-D replica and clay was sculpted to make the facial muscle and fat appropriate for her height, age and state of health.

The size and shape of her nose, lips, eyes and ears were determined using internationally tested guidelines.

"I took a deep breath when I began constructing the clay representing her soft tissue,'' Dr Baillie said. "I knew that by the end a face would be looking back at me that, although approximate, would show features that were hers when alive.''

The clay model was cast and a silicon skin made.

The colours of her skin, hair and eyes were chosen to reflect her Caucasoid, possibly Greek, ancestry.

"It was likely that she was a Greek person living in Thebes at that time - so that helped when it came to looking at skin tone and other factors,'' Dr Baillie said.

BRENDA.HARWOOD @thestar.co.nz

BRENDA.HARWOOD @thestar.co.nz