There was not a day Esther Hippe was not grateful to the people of New Zealand for giving her a new life after she escaped East Germany.

In 1951, Esther Luise Hippe (nee Raue) was the first female migrant to settle in New Zealand from Germany after World War 2.

The stories of her former life and her dramatic escape from communist East Germany still hold several secrets. But Mrs Hippe lived her second life, more than seven decades in Dunedin, as an open testament to her promise of conscientious, thankful service.

"She was the bravest and strongest woman I knew," Mrs Hippe’s god-daughter Rita Sew Hoy said.

"She was a generous, giving person with a heart of gold who ... never looked back, only forward."

Mrs Hippe was born on February 28, 1928, in Seifhennersdorf, rural Saxony, Germany, bordering Czechoslovakia. Her hometown was the birthplace of anti-Nazi politician Anna Strohsahl and, during World War 2, housed one of the dozens of sub-camps of Flossenburg Concentration Camp.

An older brother of Mrs Hippe’s was killed during the war. Food was scarce for the family. In the middle of the conflict, she left school, aged 14.

By the time a conquered Germany was being divided between occupying Allied powers, Mrs Hippe was a 17-year-old kindergarten teacher living near her hometown, in Zittau, East Germany, under the control of the Soviet Union.

Nazi rule had been replaced by communist: not an easy time or place for an independent-minded young woman.

"I had been warned several times for not fitting in with the system; for speaking out because it did not agree with my beliefs," Mrs Hippe told a journalist early in the new millennium.

It is not clear when she met Hellmut Erich Hippe, a draper’s salesman 20 years her senior with a young son, Horst, who was in Mrs Hippe’s kindergarten class.

Mr Hippe had been a reluctant corporal in Hitler’s army.

In 1944, he was a guard at a prisoner of war (POW) factory camp, in Saxony.

Out of compassion for the 21 malnourished Allied soldiers in his charge, Mr Hippe, risking imprisonment or worse, regularly slipped small bits of pilfered meat into the grass stew the prisoners were living on.

One of those prisoners was Lance-corporal Eric Dewe, of Owaka, a driver with the 8th Army, who was captured in the North African desert a week before Christmas, in 1942. Lcpl Dewe was in POW camps in Italy and Germany for a total of two and a-half years, including about 15 months in Stalag IV A and Stalag IV B, in Saxony.

After his stint guarding Lcpl Dewe and the other POWs, Mr Hippe was sent to the Russian Front until the end of the war.

But Lcpl Dewe remembered his furtive benefactor and, after spending several months recuperating in hospitals in Czechoslovakia and England before returning to New Zealand, he contacted Mr Hippe to offer his former guard a new life on the other side of the world.

Lcpl Dewe badgered the authorities for four years, finally getting permission for Mr Hippe, his wife and Horst to settle here.

Mr Hippe’s first wife, apparently traumatised by her wartime experiences, took her own life a year before they were able to leave the country.

It is unclear what steps Mr Hippe had to take to leave East Germany. But he let Mrs Hippe know he was headed for New Zealand and that, if she wanted, she could settle there with him, if she could find a way to escape.

The arrival of Mr Hippe, 42, and Horst, 7, in New Zealand, on March 16, 1950, made the front page of The Auckland Star. But the man in round, frameless glasses and a long leather jacket made it plain he did not want to dwell on the past.

"All I ask is to be allowed to live and work in peace and to give my son fresh food and milk and air," he was quoted saying.

Lcpl Dewe, the former prisoner, took his erstwhile captor to live with his family in the Hakataramea Valley, South Canterbury, where they both worked as rabbiters.

A year later, Mr Hippe (who was known as Erich) got work at the Mosgiel Woollen Factory’s new plant near the Oval, in Dunedin — and waited to see if Mrs Hippe would arrive.

In the decades ahead, Mrs Hippe never would say much about life in Nazi Germany, nor communist East Germany. She did not want to revisit painful memories, she said. Details of how she escaped are sketchy, and tantalising.

Preparations began as soon as Mr Hippe left, but still took almost two years.

In Mrs Hippe’s kindergarten class was the son of the local Russian commandant. A friendship with the high-ranking official gave her access to special passes to visit Berlin, the divided capital that sat within the Russian zone of the divided nation. Somehow, during those visits to East Berlin, she secretly made contact with Allied officials. They agreed to give her temporary West German identification papers, complete with a fictitious address. In exchange, she was to give them her East German identity papers.

No-one could know of the plan; not even family. One day, in October, 1951, she simply disappeared.

"The last time, I never returned," she recounted 22 years ago.

"There was no Berlin Wall, but there was a heavily guarded train going between the two halves of the city."

Mrs Hippe presumed her surrendered identity papers were then used by Allied spies to infiltrate East Germany.

Having left everything and everyone behind, Mrs Hippe flew to Munich, travelled to Genoa, Italy, and boarded a boat bound for a new life.

She arrived in Auckland on November 20, 1951.

Later, she recorded her thoughts on that first day.

"This now is the beginning of a new life ... I wonder if anybody is waiting for me in Auckland or in any part of my new country. That is not fair; someone [has been] waiting for the past 19 months — my future husband and his 9-year-old son ...

"What funny, old-fashioned clothes people are wearing here ... All the men seem to be wearing hats ... Where I come from ... hats are reserved for the so-called higher society ...

"By now I am becoming aware ... that some people ... give me a second look. Could it be that I am the odd one out, that I am funnily dressed? ... "That, I think, was my first feeling of wanting to belong again, to fit in, to adopt my new country, my new life."

Mrs Hippe arrived in New Zealand with only seven days’ grace before she would be declared stateless and deported to Germany.

On November 24, two days after getting to Dunedin, she and Mr Hippe were married in St Clair Presbyterian Church.

One of those was a woman whose fiance had been killed while fighting Germans during World War 1. Forty years later, she told Mrs Hippe that when she saw them in church, an ordinary couple getting married, "peace entered her heart".

At an official level, suspicions evaporated slowly. For years, the police visited the Hippes’ home, first in North East Valley and then in Abbotsford, every week.

When they became New Zealand citizens there were 400 questions to answer.

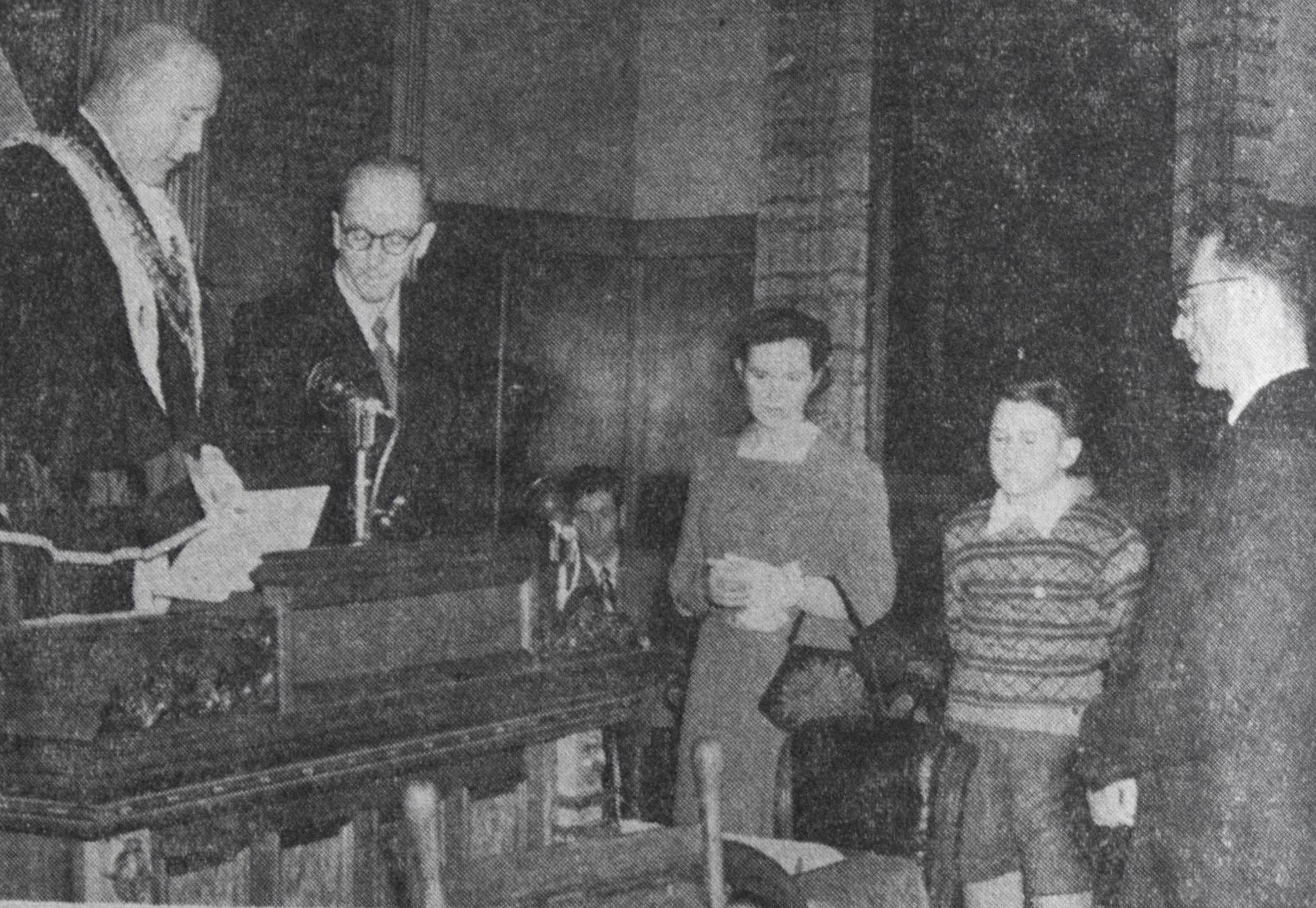

The evening citizenship ceremony, held in Dunedin’s Council Chambers, on July 28, 1955, was big news in Otago. It was the first ceremony of its kind in the city and only the fourth in the country. The Hippes’ photograph was on the front page of the Otago Daily Times; three of 16 "aliens" from Germany, Austria, Italy and Lithuania who took oaths of allegiance and became naturalised New Zealanders.

Among those new citizens were Dr George Gratzer and his wife Grete, a noted artist and portrait painter. Dr Gratzer was an Austrian of Jewish descent. After Austria was annexed by Germany, in 1938, the couple fled the country, eventually ending up in China.

For the next six years, with the country under Japanese occupation, Dr Grazter, a Catholic, served as head of medical staff at the New Zealand Presbyterian Mission Hospital, in Kong Cheung, near Guangzhou.

While there, the Gratzers got to know Fanny Sew Hoy and her children, who were in a compound in Guangzhou.

Fanny’s husband was Hugh, a grandson of Choie Sew Hoy, founder of the Dunedin-based Sew Hoy business dynasty. Hugh Sew Hoy had returned to New Zealand before war broke out, but was not reunited with his wife and children until 1947.

The Gratzers, along with all other Europeans, were expelled from China, in 1951. They came to Dunedin, where Dr Gratzer studied for his New Zealand medical degree.

When Mrs Hippe arrived in town the same year she also considered retraining, to be a New Zealand-qualified kindergarten teacher. But her limited English and the need for income led to her taking work at the Mosgiel Woollen Mill and then the Bruce Woollen Mill, in South Dunedin.

She was introduced to Fanny Sew Hoy by fellow German-speaking migrant, Grete Gratzer.

Mrs Hippe, who had learnt sewing and pattern-making as part of her teacher training in Germany, became a pattern maker for the lingerie department at the Sew Hoy & Sons Ltd factory, in Stafford St, and she became close friends with Fanny’s daughter-in-law, Shirley.

Shirley asked Mrs Hippe to be godmother to her daughter, Rita.

"I remember, during the school holidays, I would spend most of my time reading or quietly doing craft work beside Auntie Esther’s work station," Rita, a teacher in Auckland, recalls.

"My godmother was a very intelligent woman and delighted in sharing her wealth of knowledge with me."

Mrs Hippe was a "staunch, no-nonsense" woman who valued honesty and loyalty but also enjoyed conversation and laughter.

"She loved chatting ... Everybody knew Auntie Esther for her dry sense of humour and her abundance of stories."

A devout Christian, Mrs Hippe was known to interject during sermons with personal observations.

She was also a "wildly creative" person who knitted, crocheted and drafted her own patterns for clothes she made.

"At the time, I didn’t realise how fortunate I was to have so many pretty garments and wool ensembles hanging in my closet," Rita said.

In the early days of their life in New Zealand, Mrs Hippe, Mr Hippe and Horst (known as Harry) regularly visited Lcpl Dewe and his family, who by then had a small farm in Waimate, South Canterbury.

Lcpl Dewe’s son, Colin, 73, remembers more than one occasion on which the Hippes arrived by motorbike — Mr Hippe in front, Horst as pillion and Mrs Hippe in the sidecar — and then pitched their tent in the front yard.

Mrs Hippe was a mother-figure to him, Colin Dewe, an artist, of Greenfield, Southland, said.

"My main memories of Esther are of a strong, caring woman who never complained about what life had thrown at her.

"She was forever grateful for the compassion shown by two men that allowed her to be safe in a new land."

That gratefulness found myriad expressions. In 2012, Mrs Hippe was in Dunedin’s The Star, calling on fellow seniors to knit for charity organisations.

During the previous seven years, she had knitted more than 450 children’s woollen jerseys — more than one pullover a week — for Operation Cover Up, a charity helping needy children in Eastern Europe.

Since 2005, she had also knitted 40 blankets for the charity and crocheted 74 baby shawls for patients in Dunedin Hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit.

For two decades, Mrs Hippe collected used stamps from businesses. Mr Hippe would spend each evening cutting the stamps from envelopes. The stamps were given to the Presbyterian Church, which sold them by the kilo to raise funds.

Mr Hippe died in 1997, aged 90. Horst, who had been living in Christchurch, died in 2021.

In January 2022, Mrs Hippe, who repeatedly said she planned to live to be 100, went in to care at Leslie Groves Hospital, Dunedin, after having several falls.

She and Mr Hippe received many offers of payment for their story, but caution on behalf of extended family still living in Germany and an unwillingness to relive experiences always made them refuse.

During her seven decades in New Zealand, Mrs Hippe never returned to Germany and only twice saw people linked to her first life. The first was a close childhood friend, who visited, in 1997.

Four years later, a niece, born a year after Mrs Hippe escaped East Germany, visited for two months, the first blood relative she had seen in half a century.

At the time, Mrs Hippe recalled her first glimpses of New Zealand, 50 years earlier.

"It was a beautiful sight, sailing round the top of New Zealand and seeing the high cliffs with green tops.

"When I stepped on to New Zealand soil, I felt it was freedom in paradise.

"That is still how I feel about this place."

Mrs Hippe died in November aged 95.