Racism was rife in New Zealand in the 1900d, and Chinese were among those targetted. Ron Palenski discovers the story of a Dunedin man who became the only Chinese soldier in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force to be commissioned.

The country had imposed a poll tax on Chinese in 1881 which restricted the number of immigrants to one for every 10tonnes of cargo and a landing tax of 10 (about $1700 today) on each. This was increased in 1896 to one for every 200tonnes and the tax jumped to 100 (about $19,000).

There was more. By 1908, Chinese in New Zealand could not be naturalised; any who wished to leave New Zealand temporarily had to be thumb-printed (no-one else did); and restrictions were tightened even more after the war until finally the poll tax ended in 1934.

People in the immediate pre-war years would have known the name Lionel Terry, the white supremacist who randomly shot and killed an elderly Chinese man in Wellington in 1905.

This was a time when the phrase "yellow peril" was freely used. Why, therefore, would a people so unwanted and persecuted by law want to fight for New Zealand and the Empire? Why would they volunteer to wear the uniform of the country that oppressed them? But some did. A tiny number as a proportion of the huge numbers of men at arms, but enough.

An Australian researcher, Alastair Kennedy, calculates that about 150 Chinese were eligible to serve in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force and about 50 did so.

The Chinese families in Dunedin were well known and contributed to the wider community in a variety of ways. Two brothers, Howard Cecil and Albert Peacock Alloo, were among the 50, and Cecil, as he was known, became the only Chinese soldier in the NZEF to be commissioned.

The institutional racism was not confined to New Zealand. Australia was known for its White Australia policy and enacted similar laws to New Zealand. So too did Canada and California. It wasn't just Chinese either. During the 1899-1902 Boer War, New Zealand was told by the British Government it was a white man's war and that Maori would not be welcome (although some served anyway). In the early months of World War 1, Maori were packed off to Malta, not wanted as fighting troops, until protests and circumstances allowed them to take part in the Gallipoli campaign.

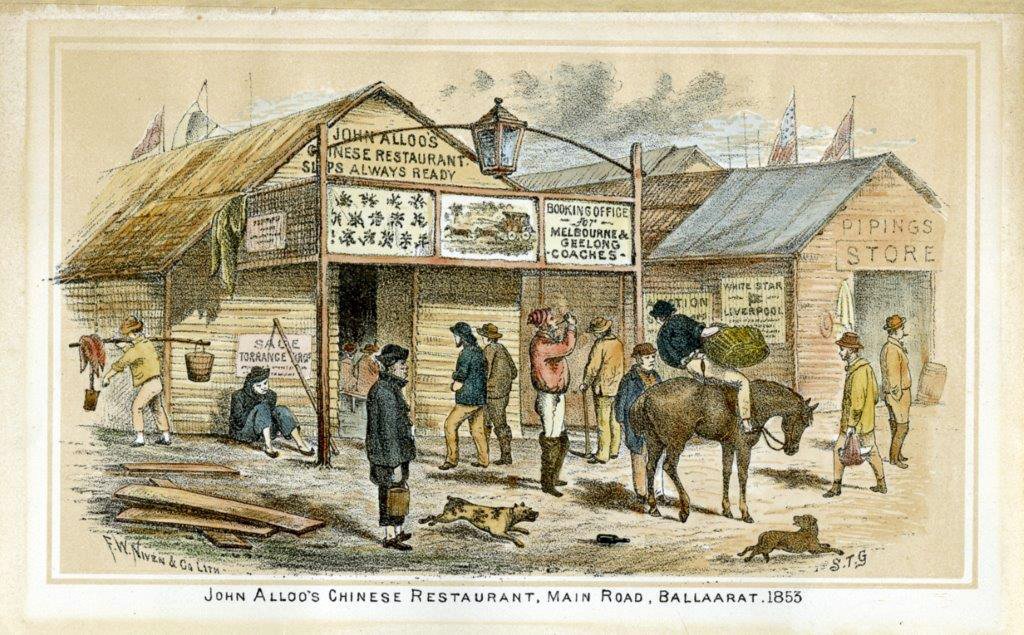

The Alloo boys were sons of William and Marion Alloo. William was a son of John Alloo, a goldfields interpreter in both Victoria and Otago. In Ballarat, John also had a popular restaurant which gained wider, lasting fame when sketched by a noted colonial artist, S.T. (Samuel Thomas) Gill. Young William, born in Melbourne, came to Dunedin with his parents but later returned to Australia where he worked as a linotype operator. He married Marion Arthur in Sydney and after the birth of three sons there, they made their way back to Otago. William worked for the Otago Daily Times, edited and published magazines and for a time ran the bookstall at the Dunedin railway station. The boys went to Otago Boys' High School and, amid other accomplishments, all played cricket for Otago. The oldest of them, Arthur, also played for New Zealand.

Cecil's war began in September 1915 when he was 20. He'd had military experience with the cadets at school and with a territorial unit, the 4th Otago Regiment, between 1911 and 1913. Part of the Eighth Reinforcements, he was shipped off to Egypt in 1915 and landed at Suez the week before Christmas - and was thus spared the tail-end of the Gallipoli campaign. Alloo was a corporal on the troopship but, as was normal, reverted to the ranks when the reinforcements draft was absorbed into the wider force. Within a few months, however, he was a sergeant by the time the New Zealand Division left for the Western Front.

For the second half of 1916 and much of 1917, his cricket prowess was a factor in him being an instructor in trench mortars and bombing (grenades) at a British Second Army Grenade School. His throwing arm, developed by his passion for, and skill at, cricket, apparently impressed his superiors; what the arm could do with a cricket ball could equally be employed at throwing grenades. Soon after Alloo rejoined the Otago battalion in November 1917, the officer commanding the New Zealand Division, Sir Andrew Russell, recommended that he be trained as an officer and he was sent to England. There is no record but Russell, wise and experienced in the foibles of the British high command, may have considered how some men might react to being given orders by a man of Chinese heritage, but went ahead anyway. As a freshly minted second lieutenant in June 1918, Alloo was posted to C Company of the New Zealand Rifle Brigade. It was involved in the Battle of Bapaume as the Allies gradually turned the defence against the German spring offensive into an attack as German resistance weakened. Alloo was shot in the thigh and invalided back to England, not able to rejoin his battalion until after the Armistice by which time most of the New Zealanders formed part of the occupation force in Cologne.

Cecil Alloo continued his association with the army after the war, serving in the territorials and, during World War 2 on home duties, had the temporary rank of captain. His brother Albert, whose war was confined to service in England, had qualified in law and set up his own firm, which Cecil joined. He later practised in Owaka and then in Timaru.

Dunedin-born Victor Low, of the Lo Keong family that first arrived in Dunedin in 1865, was not commissioned but he made an enduring contribution to the remembrance of New Zealand at war. Low, an engineer, was reported to have done the surveying and planning work for what's known as the Bulford Kiwi, an outline of a kiwi dug into the chalk hills rising above Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire. The kiwi, painstakingly worked out by soldiers waiting for ships home, has recently been acknowledged as a monument under the British Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act (and is therefore protected).

Henry Sew-Hoy, from the noted Dunedin family, enlisted but did not serve overseas, while two of his relatives, Albert and Frank Mong, did. At least two other Dunedin Chinese, brothers Edward and George Gye, served in the Australian Imperial Force. Both were working in Sydney when the war began - 26-year-old Edward as a storekeeper and 34-year-old George as a sub-editor on the Evening News - and chose to enlist there rather than return home to do so. Both survived the war and returned to Australia.

•Ron Palenski acknowledges the assistance of Jenny Alloo and James Ng in researching this story.