(Olga)

There is something almost wilfully non-linear about the trajectory of Michael Greaves’ art. With every exhibition new subjects, new styles, and new techniques emerge — so much so that seeing two Greaves exhibitions is like seeing work by two separate artists.

Despite this, there is a commonality to Greaves’ work. Whether it is mysterious spheres floating above natural landscapes or fragile line drawings of modernist architecture, there is a feel of the constant battle between order and chaos, between human planning and nature’s entropy. The works become dark celebrations of the all-encompassing power and beauty of nature.

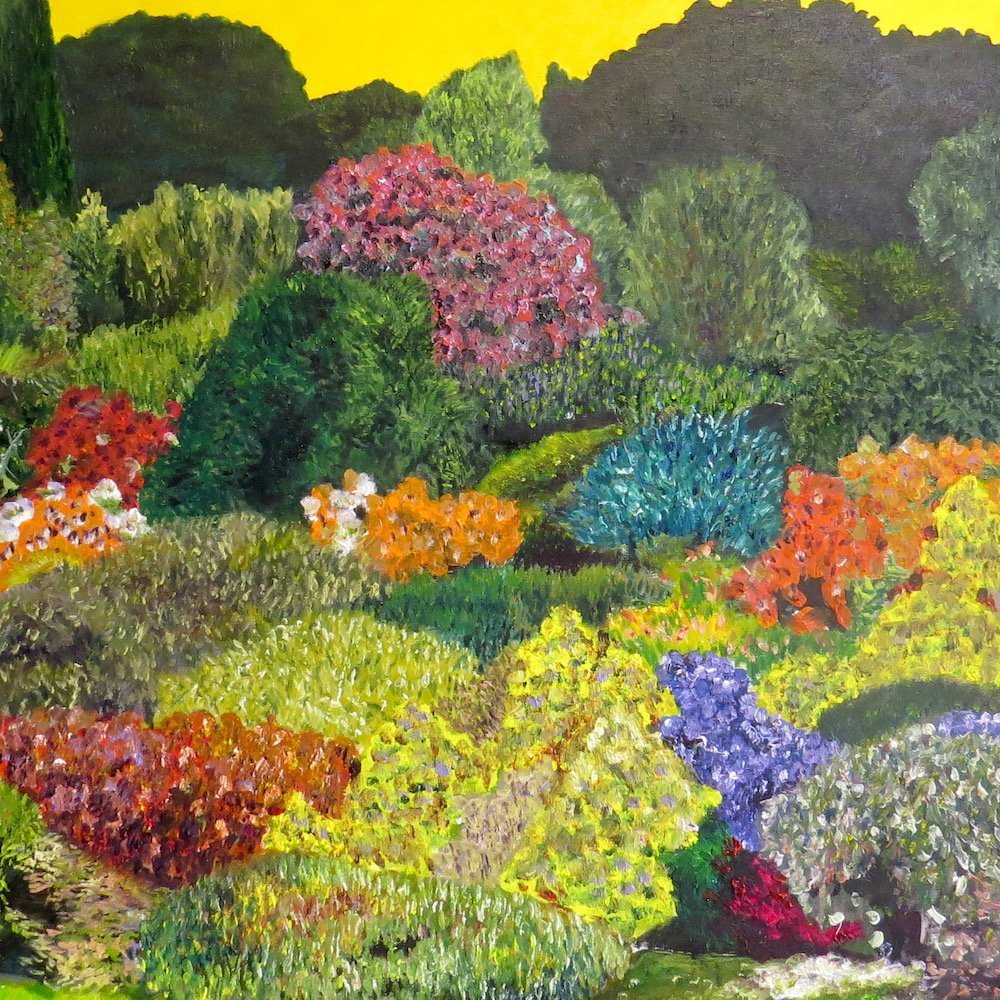

This theme is clearly evident in the artist’s latest exhibition with its cultivated gardens and their natural tendency towards disorder. The images, on the surface, appear neat — tidy horticultural gems. But on closer inspection, the spaces become claustrophobic, the blooms clashing with each other under ominous yellow skies. The titles of the works add an extra level of unease to the pieces.

Greaves has used a strong, painterly style, working from small dabs of colour — an approach he has had to adopt as the result of nerve damage to his hand. This coincidence, of the artist’s skills being countermanded by the actions of nature, makes the resulting works even more poignant and unsettling.

(Brett McDowell Gallery)

A battle between rigour and chaos is also present — albeit in a completely different form — in the work of the late Martin Thompson.

Thompson was a remarkable character, one of those loved eccentrics that the art world is seemingly filled with. First in Wellington, and later in Dunedin, he could frequently be seen sitting outside a cafe making minute mathematical patterns on graph paper. Something of a savant, he could calculate complex fractal patterns in his head, recording the resulting images on his paper in a way that mathematicians are still puzzling over.

Because of his manner of work, Thompson’s intricate grids often appear less than pristine — coffee and tobacco stains add an aleatory note to the precision, as does his cut-and-paste method of fixing flaws in his patterns. And yet, while these could be considered flaws, in a way they make the work more poignant. This is the human condition in action. As with Michael Greaves’ gardens longing to break free from their bounds, Thompson’s arts show an all too human attempt to create mathematical perfection against a background of chaotic accidental marks, a vainglorious attempt to wrestle entropy to a standstill.

Thompson’s grids are remarkable pieces, with a beauty akin to Islamic architecture, and as mind-bending as the most complex Rubik’s cube.

(Koru Gallery)

Joanne Craig’s exhibition at Koru Gallery features a series of acrylic paintings of native birds.

While these are wildlife studies, the term portrait is perhaps more accurate. Several of the pieces use the same sort of narrative backdrops as early studio photographs, creating images where the birds appear as inhabitants of some too-utopian backdrop setting. This is not a flaw in the works, but rather focuses attention more clearly on the real subjects. The scene-setting is perhaps most obvious in the two circular works, depicting a kaka and kereru respectively against stylised leaves, but is also apparent in a complex wood print of two tui.

In other works, more classical portrait techniques are employed, with a robin and kaka emerging from backgrounds which quickly fade to black.

Overall, the birds are finely captured, but it is in two more naturalistic images that are perhaps the most impressive in the display.

In one of these, a gull is captured in extreme close-up, taking a sip from a pool. The bird’s simply but effectively portrayed plumage and the light glinting through the water are well captured. In the other work, created with a slight embellishment of iridescent paint, a tern is finely depicted, white on white, part-way through a mid-air manoeuvre.

By James Dignan