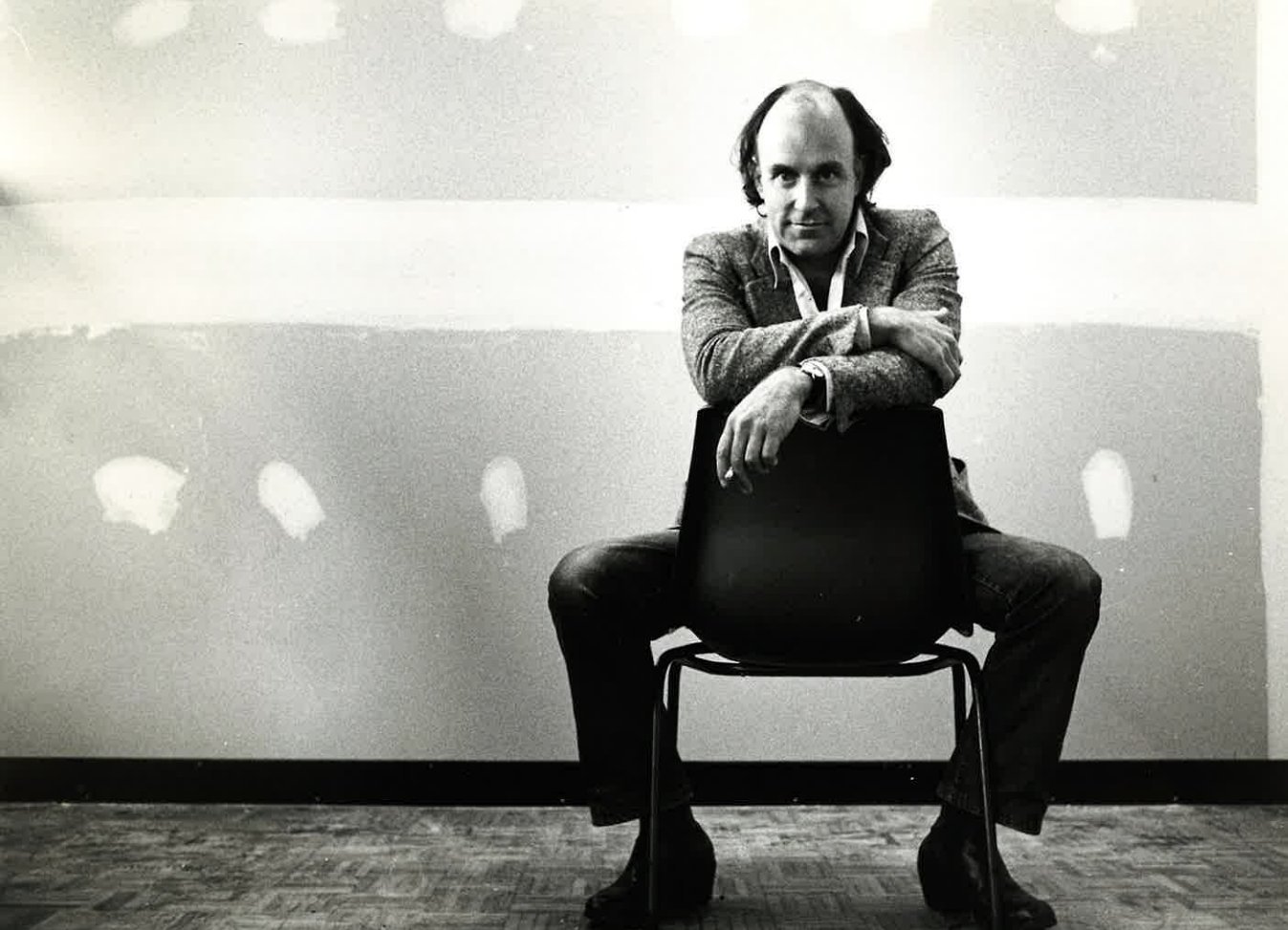

There is important absolution in the new documentary about John Clarke.

It may not have been us after all, an unworthy and undeserving public, that drove the nation’s most important humorist into the arms of Australia.

It was more complicated than that.

For this relief we have Clarke’s daughter, Lorin Clarke (who hereafter will be refered to as Lorin, to avoid confusion), to thank. Her documentary about her father delivers a salve for that long open wound. Indeed, on the phone from Auckland, where she’s visiting from Melbourne to help launch her film on its general release in cinemas — after a triumphant tour in this year’s Whānau Mārama film festival — Lorin generously wraps blame around her own shoulders.

"I went to the Auckland writers festival in 2018 and a woman came up to me at the signing table and said, ‘are you the baby?’" the writer, director, podcaster and columnist says.

"And I realised that she sort of had me in her head as this Yoko Ono figure that had broken up the band. Because he'd gone to Australia to have a baby, and it was me."

It was indeed a factor, she says. Her parents had been tossing up between the two sides of the Tasman, but settled on Melbourne to be nearer her mother’s family for when she arrived.

Lorin’s not copping the full jug of responsibility, though. New Zealand’s perennial problem of scale was also in play. We don’t have any.

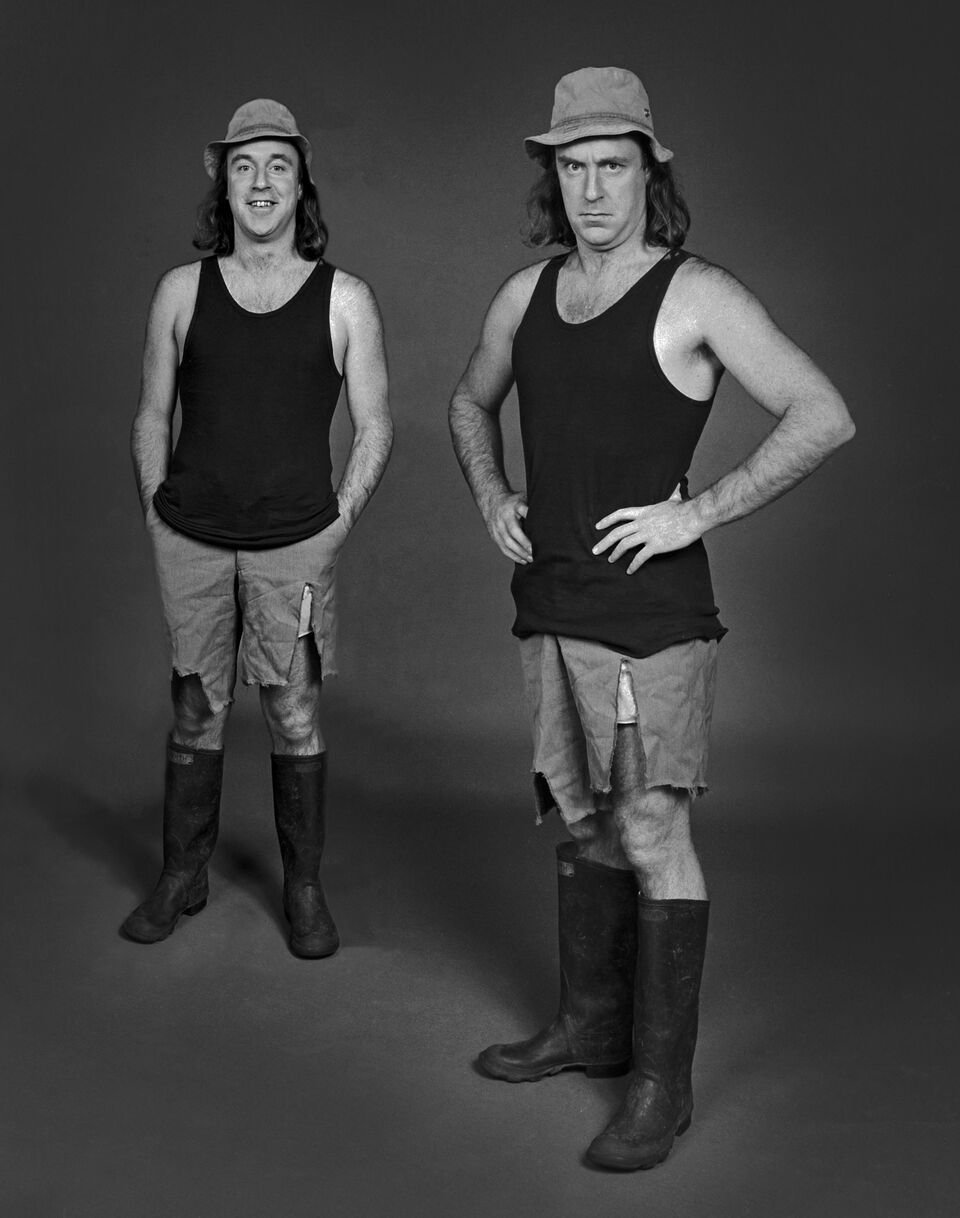

In the years before the Clarke family’s move leftwards to Australia, John Clarke, or at least his character, John Dagg, had blown up bigger in Aotearoa than the proverbial charioteer.

"The whole Fred Dagg period was less than four years long — it was pretty fast moving," she says.

By the end of that period, the second half of the 1970s, Dagg had become a celebrated fixture of the small screen, a charting songwriter and prolific purveyor of vinyl records and starred in his own film, Dagg Day Afternoon.

So, mixed up in the decision to move was an instinct to look after the character of Fred Dagg, to not dilute it or overplay it.

"He couldn't really be something else, but he didn't want to overstay his welcome with the Fred character."

Generously, Lorin confirms that it was a tough call.

"But it was the only call in a way. You kind of can't see how he could have done it any other way."

Director Lorin Clarke teases a good bit of extrapolation from her father’s early life and his relationship with his war-damaged parents.

Their service in World War 2 had left deep and permanent scarring, their lives stolen by a global catastrophe — an experience common to so many parents of the boomer generation.

It manifested in Clarke’s early life in a difficult relationship with his father. However, for Clarke, it was ultimately grist for the mill, material to be used to unlock an understanding of the human condition.

Both his father and the principal of the school to which he was sent were particularly hard on him, dismissive of his potential, Lorin’s documentary explains.

But Clarke wasn’t having any of it.

"He just didn't. In his heart of hearts, he did not believe them when those things were said," Lorin says. "I think that is pretty powerful. And it sort of enabled him to be 100% himself as well."

It also allowed him to see the way systems work, she says, what lies behind the world as it presents.

Lorin draws a line from Clarke’s precocious understanding that, in their bickering, his unhappy parents were both simultaneously right and wrong, to the approach he and Bryan Dawe took in their long-running Clark and Dawe interviews for Australian television.

They did not get personal, she says. Her father was always zooming out to reveal the bigger picture, as the best comedy does.

Those formative relationships also informed a lifelong and visceral loathing of authority that manifested in screeds of correspondence with parking inspectors and other functionaries, Lorin says.

We can be sure they were hilarious. The film confirms Clarke’s propensity and perspicacity for finding the humour in all things — and the closely related facility for subverting convention and expectation.

At one point, we’re treated to a short phone message he leaves for his daughter. It’s an event at the most prosaic end of the everyday, but Clarke turns it into skit genius.

Lorin is happy for us to bask in the reflected glory of it.

"I reckon he would consider Kiwis to be the clubhouse leaders when it comes to being able to make fun with this moment right here with only language.

"He said, ‘there is nothing more boring, you know, than some of the days or some of the hours spent in a shearing gang. But I had some of the funniest times in my life, because these people were gifted conversationalists and they could make anything funny or interesting’.

"And that, to him, if anything in life is worth celebrating, that is it."

He was always breaking new ground, Lorin points out, from being the first person to talk in a Kiwi accent on New Zealand television, to those deadpan Clark and Dawe interviews, performed without costume or props, and the TV series The Games, which beat The Office to the punchline by a fair margin.

His ability to pull it all off lay, at least in part, on a conspiracy with the audience — as evidenced by feedback from a Clark and Dawe fan.

"One of his favourite bits of feedback was somebody who said, ‘I loved those interviews. I watched them with a straight face, and then I laugh at the news’. I just thought that was delicious," Lorin recalls.

In much the same vein, a keen watcher of The Games described it to him as "a secret between the people who are making it and the people who are watching it".

"So yeah, I think it was a good trick, and he pulled it off early and often."

Lorin says one of the few documented instances of her father getting angry was when one of his editors at the ABC told him they didn't get The Games.

Clarke had considerably more faith in his audience.

"I think paying your audience the compliment of thinking they're the smartest person, that's something that he relied on.

"He learnt to trust his audience in New Zealand when he was Fred Dagg ... And I think it paid off. It's kind of why I wanted to do the film, to kind of go, well, and thanks, guys."

All indications are that Clarke would sing along with that assessment.

"I've heard him say it a million times, his big strength was he didn't think he had any particular skills, particularly to start off with, but that he came from his audience," Lorin says.

His audience saw something real in him, because authenticity was what he treasured.

"He’s famous for talking to anyone and everyone for hours, and I think he kept his ear to the ground. He was a listener and a curious person, and I think that probably is what that was, that people could see.

"He would find out the interesting thing about somebody faster than anyone. He really did have a gift for that. I don't know what he would have been if he wasn't a satirist or a writer or a performer, but his ability to get to the heart of something, particularly if it involved humans, was a pretty wonderful thing."

The film

• Not Only Fred Dagg opens in cinemas next week.