For three months, the Central Stories Museum & Art Gallery in Alexandra is giving over all of its temporary exhibition wall space, three galleries, to the largest exhibition of paintings by Elizabeth Stevens.

In 1970, Stevens' work was on show in Auckland alongside that of most of New Zealand's major visual artists. Her faceted abstract Still Point, painted in 1967, was hung with works by, among others, Colin McCahon, Ralph Hotere and Doris Lusk.

Her paintings are in dozens of private and public collections, including Te Papa, Dowse Art Museum, Dunedin Public Art Gallery and the Hocken Library.

But when she died in 2008, aged 85, it was in relative national obscurity.

That is starting to change. This exhibition of 71 paintings by Stevens, spanning four decades, is the next step towards having her recognised as a major figure of Central Otago visual arts.

Christchurch art consultant Grant Banbury visited Stevens at her home in Alexandra several times. He has written about her for the periodical, Art New Zealand.

"I wrote it to highlight an artist who lived rurally, away from the main art centres, but someone who had work in some major collections," Mr Banbury explains.

Stevens was born in Invercargill, in 1923. She was working by the age of 15, but later trained at both the Dunedin School of Art and the teachers' college.

In the 1950s, at the suggestion of influential art lecturer Gordon Tovey, Stevens moved to Alexandra to trial his new art teaching method in the area high school.

She soon met Geoff Stevens, they married, she left her job and they started a family.

She gave herself two years to see if she could sell a painting.

Charlton Edgar, who became director of the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, was so impressed by what he saw that he gave Stevens her first solo exhibition in the mid-1960s.

After the 1970 group exhibition in Auckland, she staged several other group and solo exhibitions. Stevens won the Otago Art Society Centennial Prize, in 1976, the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts Caltex Award, in 1980, and the Academy's Merit Award, in 1985.

"My question was, what had happened to this artist?" Mr Banbury says.

"She was very visible for a period. And then, perhaps, no longer visible."

He suggests it resulted from her rural isolation and her lack of a strong advocate.

"Like a lot of artists that operate in rural New Zealand, it's hard to get traction ... you need people to champion you.

"She accepted that [she was staying in Alexandra], and made the best of living in that environment, which did inspire her."

In 1997, the Eastern Southland Gallery, in Gore, put together a survey showing her work. But it only toured in the South Island, leaving the North Island largely in the dark about Stevens.

Banbury sees an originality in Stevens' art.

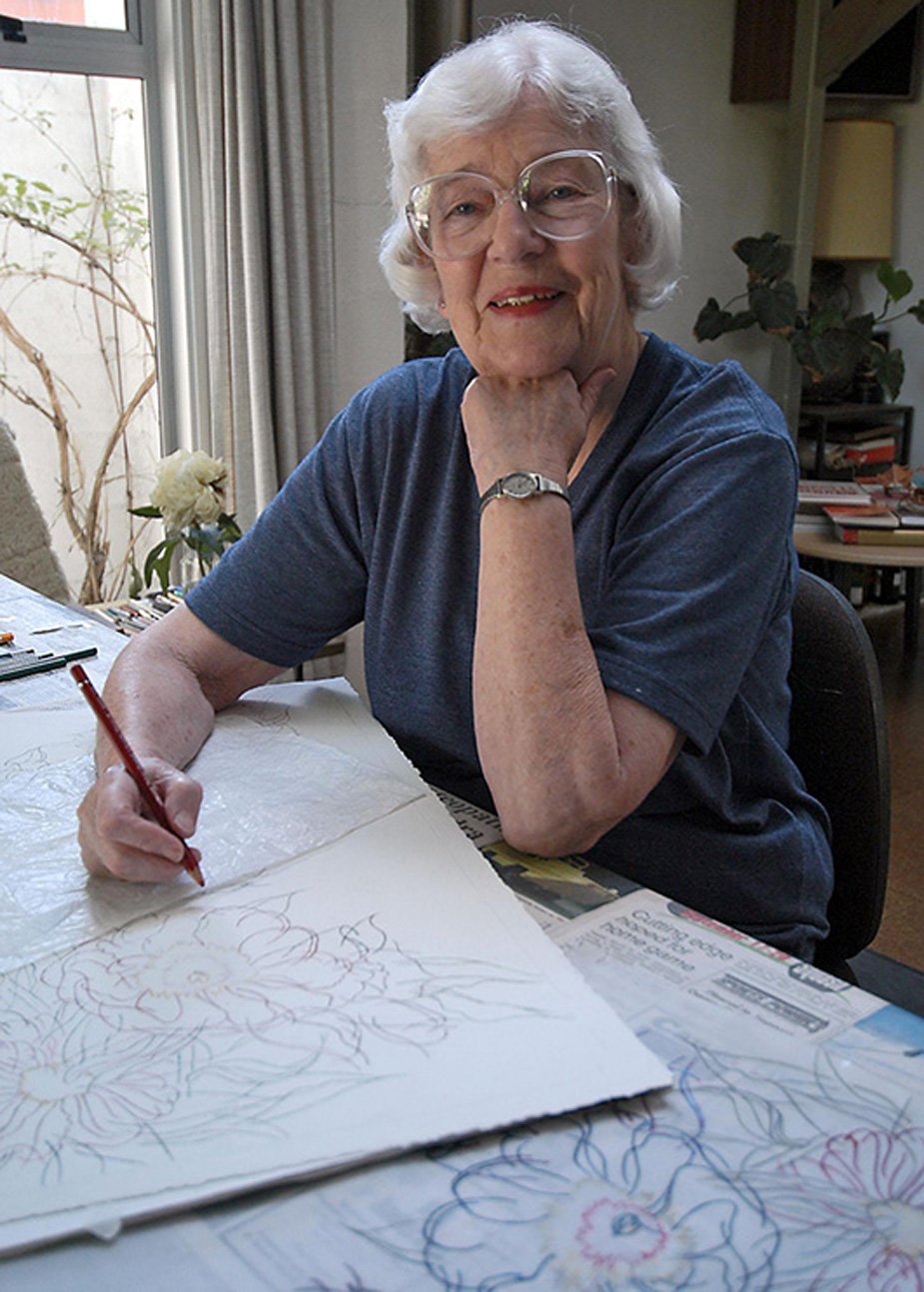

"She works in a very detailed and considered way.

"Rather than being cubist ... the faceted divisions became her signature style."

This is seen in both her landscapes and some of her moody interiors, which, at their best, generate a spiritual dimension, he says.

Claire Stevens, of Dunedin, says her mother-in-law was a meticulous and focused artist.

"She was single-minded in her commitment to her work," Ms Stevens says.

"Painting was never regarded as a hobby. It was her work, which gave her confidence and enjoyment despite hours of often tedious underpainting, over painting, washes, glazes, and endless stipling with a very small brush.

"She coped with almost constant back pain but persevered to get the end results she wanted."

"She aimed in her work, to make order out of chaos."

This aspect of her character and her art is reflected in the title of the current exhibition Re-discover Elizabeth Stevens: Creating order from chaos.

Ms Stevens says her mother-in-law was an intelligent and well-read woman who had strong opinions.

"She used to rail at the television when George W. Bush was on. I hate to think what she would have said of Trump.

"There were just some things she really didn't like. She hated consumerism."

For an artist who did not seriously begin painting until in her 40s, held her last exhibition on her 80th birthday and believed she worked quite slowly, Stevens was quite prolific.

She is known to have created more than 750 works. But the whereabouts of only 250 are known.

Mr Banbury says Central Stories general manager Maurice Watson and his team have done an outstanding job with limited resources to bring 71 of those works together.

Mr Watson says he became increasingly fascinated and impressed by what he discovered about Stevens.

"Her's looked like a really good story, and when we dug into it, it blossomed," Mr Watson says.

He hopes the exhibition will be part of making her a well-known role model for budding artists.

"She's a major icon for the visual arts in Central Otago.

"She's one of the people who changed the way people look at the Central Otago landscape."

Mr Banbury says Stevens' contribution to New Zealand art needs to be considered more thoroughly.

"She is one of a whole range of artists who could have more work done on them."

He believes her original approach to abstraction has enduring significance.

"The isolation allowed her to operate in her own way.

"It is her faceted work that I think is her major contribution."