Southland farmer Jason Herrick watched helplessly from across the Tasman as the October storm wrecked his family’s lifestyle block near Invercargill.

Herrick, Federated Farmers’ Southland provincial president, was at a family wedding in Australia. But modern technology ensured he did not miss seeing the destruction.

"We’ve got security cameras at our lifestyle block and that’s what I was watching it on. But also hearing the reports, and being in the position I am with Federated Farmers, I felt quite helpless."

The October 23 storm ripped across Southland and South Otago in the middle of the day, tearing up trees and fences, flattening power poles and cutting electricity and communication links, lifting roofs and destroying small buildings. These were the worst onshore winds for many years.

Winds reached violent-storm force — Force 11 on the Beaufort Scale — and in exposed places averaged more than 110kmh for an hour or longer. Maximum gusts included 194kmh at Southwest Cape, 190kmh at Ruapuke Island, 178kmh at Centre Island, 164kmh at Nugget Point, 154kmh in Balclutha, 137kmh at Invercargill Airport and 124kmh in Gore.

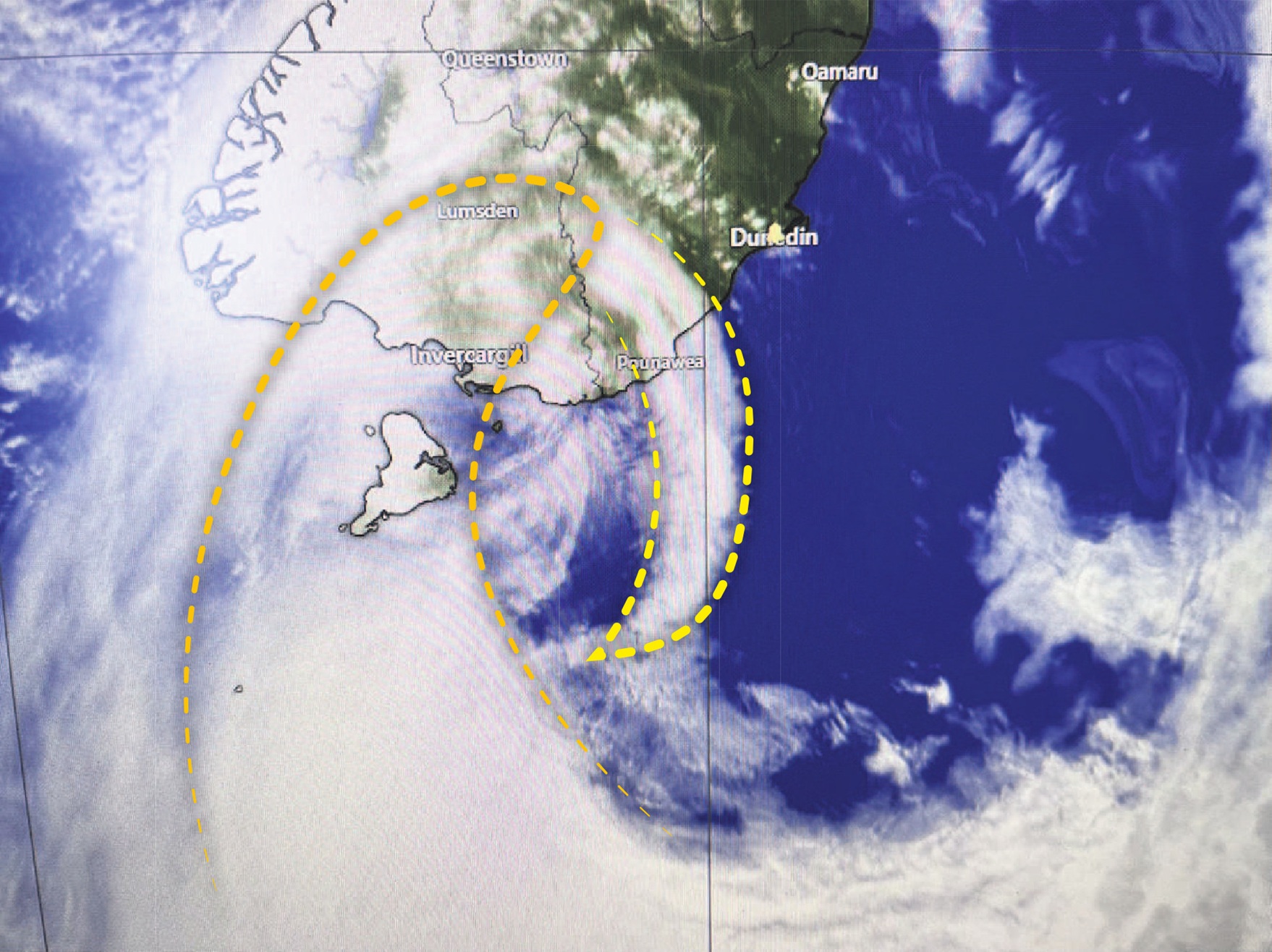

There was little warning of how ferocious the west to southwest change would be, which roared through Foveaux Strait on the back edge of an extremely deep low-pressure system, with central pressure of 958 hectopascals, just off Stewart Island.

MetService had issued an orange severe wind warning for much of the South the day before and that Thursday morning gradually lifted the likely gust speeds for coastal Southland and South Otago to 140kmh.

Two minutes before noon, by which time winds were starting to cause damage, MetService forecasters upgraded the warning to red, the category reserved for the worst and potentially life-threatening conditions. This new warning predicted destructive gusts of 150kmh, with "threat to life from flying items and falling trees" and advised people to "seek sturdy shelter away from trees".

Southlanders are well used to strong winds. But this was something else, Herrick says.

"Fifteen minutes before it hit is when we actually got the red warning. A message got sent to me on my phone: ‘Have you seen the weather update?’ And I looked it up on my phone, on my wind app, and I’ve never seen that colour before. It wasn’t red, it was black. And I thought, ‘oh dear’.

"I logged into my cameras and watched it. But within 10 minutes the cameras went blank because the power had cut out.

"I’ve never seen a weather event like that before. It has happened in the past, but I haven’t seen it in my lifetime."

MetService meteorologists and others believe what hit the South that day was a "sting jet", a rare (in New Zealand) corridor of tremendous winds that blasted down to the surface from higher levels as the low-pressure area deepened rapidly. Sting jets can cause considerable damage within quite a narrow band.

Climate Prescience founding director Dr Nathanael Melia, a senior research fellow at Victoria University of Wellington, says the phenomenon is named after its visual appearance on satellite imagery, with the quickly moving cloud formation resembling a scorpion’s stinger at the end of a curved tail.

A sting jet is one example of the kind of extreme weather phenomenon occurring on a regional or local level that current climate models cannot predict accurately.

"Studies of European windstorms indicate that climate change will increase the frequency of strong jets. [But] it’s not intuitively obvious to me why climate change would make sting jets stronger," he says.

Climate change isn’t patient and isn’t kind. It’s not going to wait for us to catch up.

Yet in the past couple of years, rather than merely struggle to keep up, the National-led coalition government seems to have actively put our climate-change efforts into reverse.

It has proposed sweeping changes to the Zero Carbon Act that will undermine the operation of the Climate Change Commission.

The government does not want the commission’s advice on how it can meet carbon budgets in the commission’s five-yearly emissions plans, which the government will be able to alter or replace without consultation. Progress reports on how well New Zealand is doing in adapting to climate change will no longer be required three times during the life of each five-year adaptation plan but only once.

The Zero Carbon Act attracted near unanimous support when it was passed by Parliament in 2019 with the backing of both the National Party and the Labour-New Zealand First-Green Party coalition, after more than a year of discussion.

The current government’s most recent move is the dilution of methane emissions targets for 2050, halving an initial 24% to 47% decrease from 2017 levels to a 14% to 24% reduction by mid-century.

Watts said a lot of work was being done on farms to cut emissions and that New Zealand’s international goal of halving net greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 had not changed.

He may want to talk to his party’s finance minister, Nicola Willis, about that. Earlier this month she ruled out buying offshore carbon offsets to meet that target — the only way the country can do it, according to most observers.

Earlier this year Massey University Distinguished Professor in Applied Mathematics Dr Robert McLachlan estimated the country had no domestic plans to meet a 93 million tonne CO₂-equivalent shortfall in its 2021-2030 carbon budgets.

Until Willis’ statement, it had been assumed we would be paying others, offshore, to cover that gap — a bill that would run into the billions. It appears Watts now has one less tool in his carbon cutting toolbox.

Asked if he can think of anything positive New Zealand is doing about climate change, anything to feel proud of, Victoria University of Wellington climate scientist Prof James Renwick looks bemused.

"As a former climate change commissioner, and an academic in the field, I can’t really.

"We were doing some great things a few years ago, but the current government has pulled back on the good things the previous government set up. And now they’re gradually undermining the commission and the Zero Carbon Act, and the agriculture sector is getting an absolute free ride. But they’re spending, what, $50 billion on new roads?"

Renwick’s five-year term as a commissioner ended last December.

"The commission has the same sort of philosophy as the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. It is an independent government agency, but that’s the thing — it’s a government agency. When you’re a commissioner, you’re a public servant and you’ve got to sign the form to say you won’t rat out the government, basically.

"While I was a commissioner, I still appeared in the media but I never had much to say. So, I’m free to let rip now.

"I absolutely have all the time in the world for the commission itself. The people who work there are brilliant and doing great work, but they’re underfunded and under-resourced, and now they’re getting undermined, basically. They’ll never say that in public, but that’s what’s happening."

Greenpeace executive director Russel Norman says the commission was never designed by the previous government to have any real power.

"If you were serious about the commission, you’d want their job to be making sure we are on track with emissions and the price of carbon. You could punish a government that isn’t doing anything.

"But we are right off-track in terms of climate change. The current government can get away with all its policies to increase emissions."

While the government may claim it is fast-tracking renewable energy projects, many solar farms were actually already under way as part of the earlier Covid-19 fast-track programme, Norman says.

It has also effectively blocked significant offshore wind-energy projects by wanting to fast-track sea-bed mining off Taranaki. Three of four energy companies have already withdrawn wind projects there.

Watts told the Weekend Mix the commission provided independent advice that the government could consider "alongside other government priorities and objectives when making climate-policy decisions".

His office sent a list of the government’s achievements on climate change.

While including a good number of bullet points, the list is heavy on report writing and setting targets — arguably lighter on delivery.

It includes releasing the government’s climate strategy and the second Emissions Reduction Plan, "showing how we will meet our domestic emissions target for the second half of this decade".

Then there’s "setting a target" for reaching 10,000 charge points by 2030, and updating the way government co-invests in public chargers with the private sector "to accelerate the uptake of EVs across NZ and lower emissions".

It might be noted that EV uptake has significantly slowed since 2023.

Watts’ list continues, noting changes to market governance of the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme and the confirmation of annual ETS decisions in 2024 and 2025, providing the market with a "clear and consistent signal on expected price and unit volumes" over the next five years and limiting auction supply.

All four ETS auctions in 2025 failed to clear, only the second time that’s happened. There wasn’t a single bidder in the year’s final auction.

Other reports and strategies on the Minister’s achievements list included the Wood Energy Strategy and Action Plan and the Government Statement on Biogas, "to enable wood energy and biogas to diversify our energy mix and reduce emissions"; updated electricity and gas safety regulations, that would enable greater uptake of rooftop solar and electric vehicle (EV) charging; and a Carbon Removals Assessment Framework, a first step in enabling reward and recognition for non-forestry removals in New Zealand, according to the Minister’s office.

There was also the National Adaptation Framework, the government’s long-term, strategic approach to prepare for and respond to the impacts of climate change.

Elsewhere, Watts says the government and industry have committed $400 million to accelerate the development of new tools and technology to reduce on-farm agriculture emissions; launched a Solar on Farms initiative to support farmers to install solar and battery systems; supported regulatory changes for households exporting electricity to the grid to be paid a fair market price; expanded the Warmer Kiwi Homes eligibility criteria to include up to 300,000 households who haven’t previously qualified, and who will now be eligible for insultation grants; backed the expansion of a voluntary Nature Credits Market that connects investors and buyers with high trust, internationally credible, assured carbon and nature credit offerings; and implemented the Electrify NZ work programme to support the goal of doubling renewable energy. This includes work to make it easy and faster to build renewable energy and network infrastructure, which will help other parts of the economy switch to clean electricity, the Minister says.

However, for all the appearance of activity, Watts’ bullet points didn’t save New Zealand from another "Fossil of the Day" award at this year’s UN climate gathering in Brazil, COP30. It was the fourth time in five years the country received the award. This latest one for that decision to reduce the methane-cutting target.

That Brazil meeting is another big part of the picture here — the 30th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) — as New Zealand’s efforts don’t stand in isolation but rather as part of the global effort agreed in Paris 10 years ago.

It remains a big date on the annual climate calendar but Prof Renwick has some qualms about the COP gatherings.

The COP model of working towards watered-down agreements, which don’t upset petrostates or huge oil companies, just "kicks the can down the road again".

"It’s not a scientific conference, it’s a meeting for policymakers to do behind-closed-doors deals and that kind of thing. It doesn’t seem fit-for-purpose, but I don’t have an alternative.

"It’s the way the UN operates, it’s the way the governments of the world want to operate. This idea of allowing a majority to agree on the way forward, rather than absolute consensus, that would help a lot."

However, Renwick is unequivocal in his support of the colossal effort that goes into the five- to seven-yearly Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports.

The IPCC work acts as a reminder that the world is now overstepping the limit set in the Paris agreement of 2015 of keeping temperature rise this century to 1.5°C, and certainly well below 2°C.

"The IPCC process has been brilliant. In my opinion, there’s nothing like it in science in the world. The collation of information you get in an IPCC report is wonderful. Encyclopaedic. There’s a huge amount of detail that goes into pretty much anything you can imagine.

"We’ve reached 1.5°C and we know the remaining budget for CO₂ emissions, for stopping warming at 1.5°C, is almost exhausted. Every 10th of a degree of warming matters as it makes the extremes harder to deal with, and we get closer to the cliff edge where tipping points kick in — West Antarctic melting, Amazon rainforest loss, deep-ocean circulation shutdown etc."

Could drastic measures taken now keep that rise at 1.5°C or lower?

"There’s no known technology that would allow us to do that, beyond planting trees," Renwick says. "And there’s not enough space to plant enough trees to really make a difference.

"The best way is to stop emitting carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. It’s now well-known that when you do that, you actually reduce the amount in the atmosphere, because suddenly the atmosphere is overloaded and the ocean is going to absorb some, so that would be a way to get a little bit of clawback at the end of the period."

Could the 1987 Montreal Protocol to protect the ozone layer by phasing out chlorofluorocarbons give us hope of an international agreement on climate change?

"That was one specific collection of gases which were really only used by a fairly narrow industry. And — what do you know? — there were alternatives that were even more profit-making than the originals? So DuPont and co got right behind all that, and everyone carried on, and no-one, no individual, actually had to do anything.

"Climate change is just the opposite of that. We all drive cars and burn fossil fuels one way or another, and it powers the global economy. It’s so fundamental that it makes it much, much harder."

Supercomputers performing mind-blowing numbers of calculations every second — quintillions in fact — are now running high-resolution models that can more accurately predict our changing future climate, especially extreme weather.

But while the focus has been on understanding climate change on a global scale, most people will experience the changes on a local scale.

To focus attention on effects and responses at the community level, University of Canterbury atmospheric scientist Emeritus Professor Andy Sturman and National Centre for Scientific Research (France) climatologist Dr Hervé Quénol have written Climate Change: Impacts and Adaptation at Regional and Local Scales.

Sturman, who has spent a lifetime researching weather and climate at these scales, says it is a fallacy that "global warming" means warmer conditions everywhere.

"Broad generalisations of the effect of climate change on human activities are often not valid at the regional and local scales. The same change in climate could cause parts of New Zealand to become wetter while other parts become drier.

Global climate models that form the basis of future climate predictions are still of insufficient resolution to account for climate variations from factors such as topography, land use and proximity to the sea, he says.

Every region has its own environmental, social, cultural and economic characteristics which determine vulnerability to climate change.

"Small-scale variations in climate can have a significant influence on the nature of that vulnerability. Essentially, there is no one-size-fits-all adaptation strategy. Some regions [are] more likely to be impacted by extreme winds, while others may be more affected by intense rainfall or drought. Only by downscaling global climate models to the regional and local scale can we get an idea of the nature of this vulnerability.

"New technology such as remote sensing from satellites and the use of drones and other instrumentation has allowed improvements in the gathering of climate information, while continued growth in the power of computing systems has allowed significant advances in our ability to model climate at high resolution."

Quénol says we have been thinking too much about global effects, "because before we can study the effects of climate change at a fine scale, we need to understand the processes that control climate at the global scale".

A "lack of urgency" by the government to tackle the issues seems to reflect a trend in a number of other countries.

"The New Zealand government has not received particularly good press coverage regarding its climate-change policy at meetings such as the recent COP30 climate talks in Brazil and continues to be criticised domestically by environmental groups and opposition parties," he says.

One way scientists can work out how the changing climate may have made severe weather more extreme or more likely is through attribution studies.

To do this they can use modelling to calculate the human influence on broad-scale weather events, such as continent-wide heatwaves, widespread extreme rainfall or droughts, or on hurricanes and tropical cyclones.

Back in Invercargill, Herrick says all sorts of natural phenomena, from flooding to wind to earthquakes to fire, threaten farming resilience.

"I encourage farmers to definitely build some business resilience and have a real good hard think about how to protect your assets. Make sure that you are able to continue to operate after a severe weather event.

"We’ve got to learn to adapt to a climate that’s always changing."

Stings in the tail

Would it be possible to analyse the South’s sting-jet storm to see how much human-made climate change was to blame?

It would be difficult, University of Canterbury physics professor Dave Frame says.

"Extreme wind is quite hard to look at in attribution studies, because the models we use struggle to do wind on the relevant scales for this sort of storm.

"Basically, models do pressure gradient winds OK, but really damaging events in New Zealand like the other month were quite localised and depended on topography, and sub-25km-grid scale processes that the models can’t quite capture.

"We are hoping that a new approach using weather forecast models in attribution set-ups might help, but wind is inherently pretty tricky."

Dr Luke Harrington, a senior lecturer in climate change at the University of Waikato, says it may be possible if there was funding to carry it out.

"Any attributable signal for a windstorm will be much smaller than for a heavy rainfall or drought event, which in turn have much smaller attributable signals than extreme heat events."

An attribution study of February 2023’s Cyclone Gabrielle had calculated that without anthropogenic warming the storm would have produced about 10% less rainfall, with peak hourly rainfalls 20% lower than experienced.

Harrington says the Earth Sciences New Zealand Natural Hazards and Resilience Platform had determined it was worth carrying out rapid research into the October 23 storm to, in the platform’s words, "inform recovery and resilience". The platform said focuses would be weather warnings and watches and human behaviour, and social and economic impacts of infrastructure disruption.

"So, no attribution analysis."