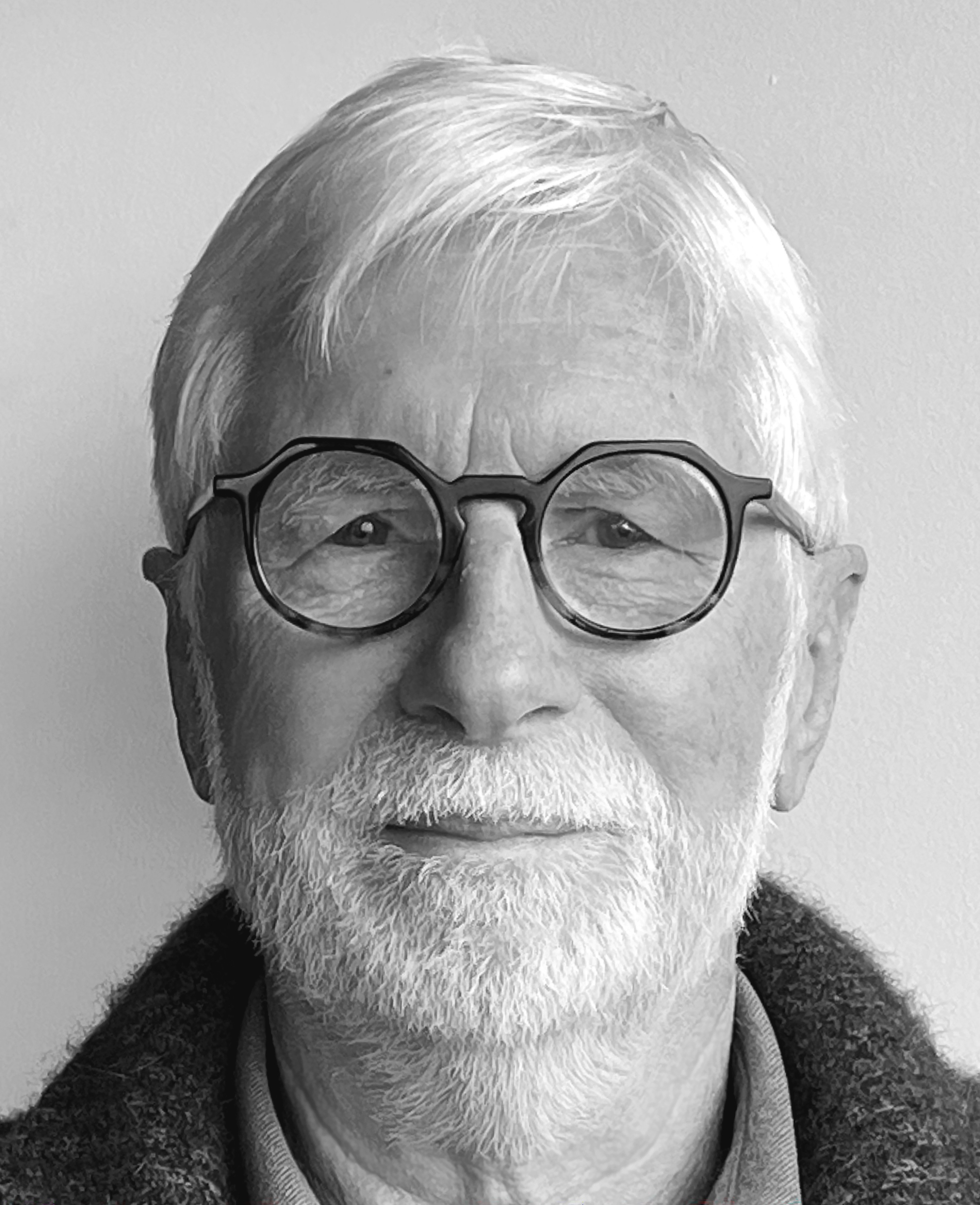

Endearingly modest, he said shortly before his death from prostate cancer on October 2, aged 83, that there were only two reasons why anyone should write his obituary.

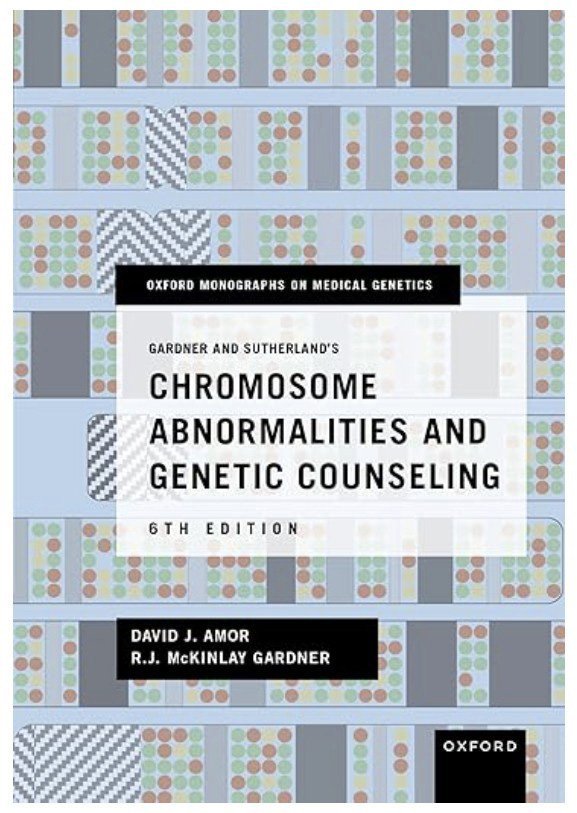

One was his co-authored textbook Chromosome Abnormalities and Genetic Counselling: "this book is used around the world and I daresay any hospital anywhere where chromosomes are tested would have one copy," he said.

"Our book has, in a sense, defined the clinical discipline."

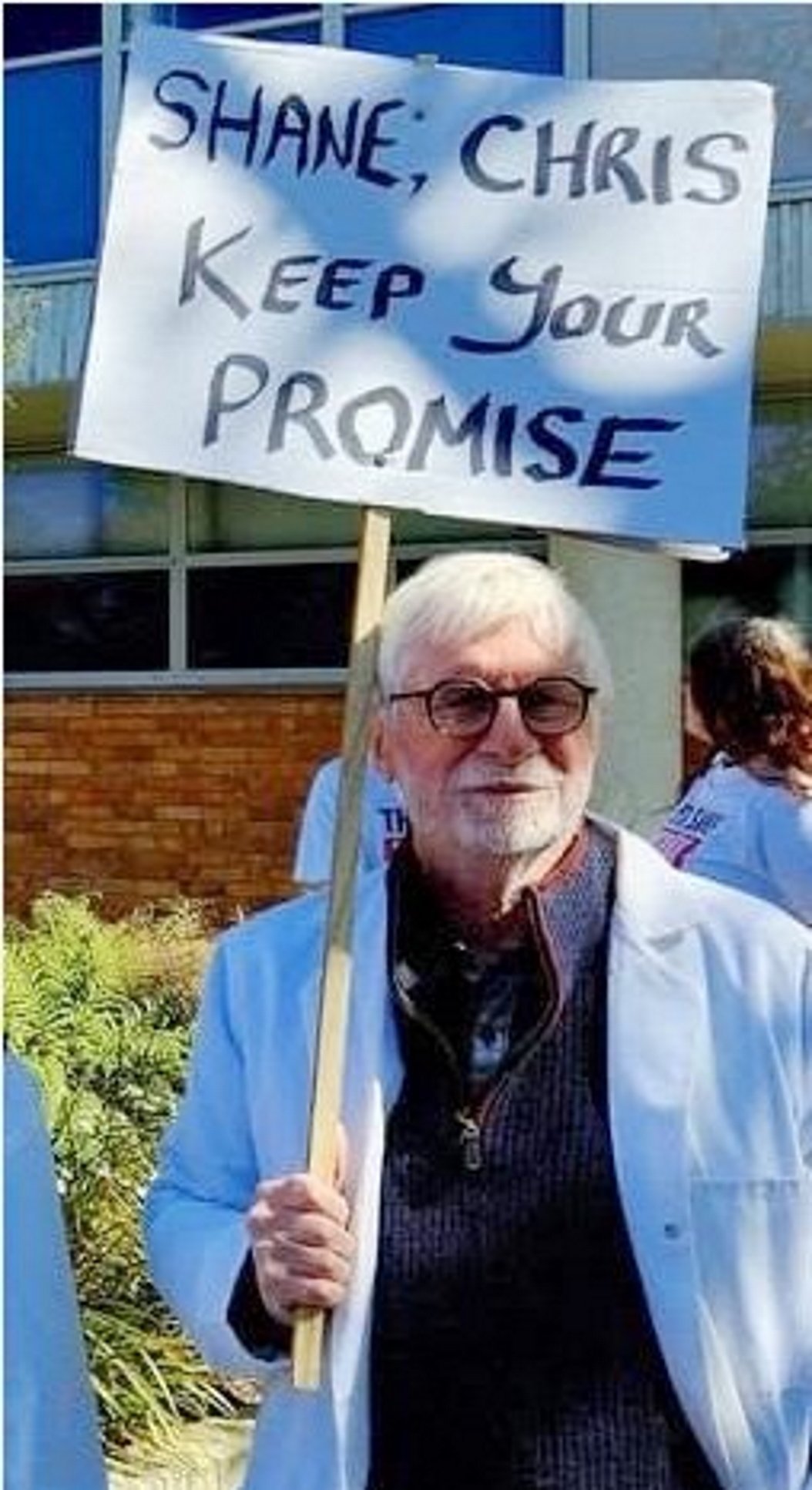

The other was his late-in-life involvement in politics. Mac took a keen interest in the drafting of assisted dying legislation, but what really got this otherwise mild-mannered and retiring doctor going was the new Dunedin hospital.

Furious at the way the construction project was — or more pertinently, was not — going, Mac launched a quixotic campaign for the hospital to be built as promised.

He first took to the hustings by standing for Parliament as an independent candidate, pushing at every public meeting for the hospital he urgently felt the people of the South deserved.

Getting just 268 votes in the Taieri electorate in no way deterred Mac. Even though he knew his death was near he literally campaigned until his final breath, paying for a series of billboards in Wellington, in direct line of sight to the Beehive, which bore pro Dunedin hospital slogans on them.

He was drawn strongly to medicine and headed south to Dunedin to study at the University of Otago, graduating in 1968. After stints at Dunedin and Auckland hospitals he then completed a master’s in human genetics at the University of Edinburgh.

After further sojourns at the Institute for Child Health (London) and the Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto) he returned to Dunedin to practise as a (and sometimes New Zealand’s sole) clinical geneticist for 16 years.

During that time the requirement to supervise and teach the small band of cytogeneticists at Dunedin Hospital seeded the germ for what was to become the widely used and eminently readable Chromosome Abnormalities and Genetic Counselling, initially in partnership with Grant Sutherland and then more latterly Lisa Shaffer and then David Amor.

Leading up to his death he was finessing the final preparatory steps for publication of the 6th edition, published by Oxford University Press, New York.

While there were numerous other significant academic publications and addresses, this was the work Mac considered his legacy.

The global reach of the book and its indispensibility for anyone counselling a family with a chromosomal anomaly set him on a pedestal as a true and enduring international citizen of the first rank in his profession.

Mac’s academic career saw him appointed Associate Professor in Medical Genetics at Otago (1977-93), Associate Professor in Medical Genetics at the University of Melbourne (2005-07) and honorary adjunct Professor in Medical Genetics back at Otago from 2008 until his death. He was also on the Medical School alumni committee.

Always humble, constantly astute and incisive but interminably curious as well, Mac Gardner was the consummate academic.

Mac’s first marriage, to Jenny (nee Brain), ended, and he married Kelley in 1993. At the heart of his world was his family — Kelley, his sons Tony, Danny and Nicky, and his grandchildren.

The couple moved to Australia in 1993 and Mac took on a role with the Victorian Clinical Genetics Service in Melbourne. His interests expanded into cancer genetics and increasingly neurogenetics, which he enjoyed immensely. His involvement in neurogenetic research, which included the clinical definition and discovery of the genes for several conditions, was a

signal joy and he thrived in the Melbourne environment.

His broad reach across many domains of clinical practice underpinned his own, frequently repeated, definition of clinical genetics as "anything interesting".

Mac returned to Dunedin to be nearer family in 2008, working as a part-time consultant clinical geneticist with Genetic Health Services New Zealand, then at Auckland, Wellington and finally Christchurch Hospital. He also did locum work in Brisbane when requested.

From 2008-25 Mac also had a research attachment with Prof Stephen Robertson’s Laboratory for Genomic Medicine at the University of Otago, which included what he described as "a modest contribution to the BMedLabSci course, and to senior paediatrics students".

His oft-repeated motto was "One must always have a project" and he always had at least five on the go.

A devotee of classical music, he had a weekly radio programme with Otago Access Radio for a time: The Classics with Mac. He enjoyed playing piano, at home and for reunions and recitals.

He was also passionate about trains and trams, and was a key part of the steering group involved in bringing back the Mornington cable cars. He was involved with the visitor centre, helping to sand and paint the cars at Ferrymead in Christchurch, and he sourced photos of cable cars from around the world to make fundraising calendars.

Until the day before he died, he was building a scale model of the workings of the underground cables.

He also owned a patch of land in the remote Central Otago hills, where he had a stone cabin built to "look like it had been there 100 years" and lined it himself with wood and bunks.

No electricity or plumbing. No heating in the cabin? No worries.

Mac had bought up every wool blanket he could find and made everyone hot water bottles. 5°C inside? No-one complained; it was part of the adventure.

Defending the integrity of the hospital project became his life’s mission. He called a plague on all houses for their handling of the hospital build; Mac blasted the iniquities of the former Labour government and the current coalition government with equal fervour.

Having been in Melbourne during the build of the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne (where he once worked), he knew that a 340-bed building could go from planning to opening in seven years and was desperately frustrated that no similar rapidity was apparent in building the new Dunedin hospital.

Mac stood for Parliament in Taieri primarily to bring attention to the travails of the hospital project. His modest political career came to a close on October 14, when he got what he called an underwhelming number of votes.

Characteristically, he wrote a whimsically funny — but also quite acute — opinion piece for the ODT all about it.

"In my naivety, I had imagined the power of the internet would carry me along but my website was never in danger of crashing due to heavy traffic, and I do not know if my inexpert use of Facebook achieved much," he dryly observed.

Soon after he penned a piece for the ODT on a very different matter: the absurd case of his South Island domiciled Honda Jazz car picking up several parking tickets in Auckland. Such writing showed that medicine’s gain was literature’s loss.

In addition, he wrote a screenplay, which he then workshopped with daughter-in-law Nina, an actor. It is now in the hands of a professional scriptwriter.

Increasingly disconcerted by the trajectory of the hospital build Mac threw himself into one final project. Putting his money where his mouth was, Mac spent more than $7000 on a series of advertisements in Allied Media publications and on a series of giant billboards in Wellington.

The first signs criticised Labour leader and former prime minister Chris Hipkins for being "incompetent" and Prime Minister Christopher Luxon for being "untrustworthy" when it came to running the new Dunedin hospital project.

He knew the hospital would not be built before he was gone, but Mac was determined it be opened as quickly as possible for generations to come.

Forever the teacher, Mac’s last poignant lesson was a personal appeal for an extension to New Zealand’s assisted dying legislation through the publication of an opinion piece in The Listener just two weeks before his own departure.

True to the integrity of the man, he chose his own death at a time and place of his own selection to be a moment for reflection for others. He made a difference, and he will be missed. — Stephen Robertson and Mike Houlahan