To her friends and family, she was a selfless, devout Catholic, who coped with the pain of fleeing war-torn Europe with her faith, quirks and a strict routine.

She died on June 7 aged 96. She was visible in the community due to her daily walks.

So visible, that her daughter Janice Rabbitt said people gave her lifts if they saw her walking by.

"I think she was the most picked up female in Gore," Mrs Rabbitt said.

Her longtime friend and fellow Pole, Renata Brumby, said Mrs O’Brien had a good sense of humour and was a very "structured person".

"Even if she wasn’t in the church going to mass, she was still in the chapel," Mrs Brumby said.

"If you were in town and you wanted to see Irena, if she wasn’t home, you’d go to the chapel."

Born in Poland in 1928, Irena was raised by her grandparents, slept on straw and only had one pair of shoes to share with her siblings.

Because of all that befell her in her early years, Mrs O’Brien felt unworthy of new things, wearing the same pair of purple crocs until they were worn through.

Her daughter Veronica Swain said Mrs O’Brien had infinite generosity.

"She’d give whatever she had on her back to anyone," Mrs Swain said.

Mrs Rabbitt said growing up, she and her seven siblings were not told much about their mother’s origins.

"It was never talked about in the family," she said.

"I remember [my dad] saying that it was too bad, you don’t want to know."

Germany invaded Poland in 1939, when Irena was 11.

Her loved ones were unsure of the specific details of Mrs O’Brien’s past because she did not like to speak of it.

"She would only tell you so much and she’d stop talking," Mrs Brumby said.

"Because you could tell there was so much hurt and pain."

The camps were separate from SS-run concentration camps but their conditions were still lacking in food, medicine and clothing, while working long hours.

Irena’s mother died in one of these camps and it pained her for years how the Germans buried her, she used to say it was like a "dump area" to her.

At the end of the war when Russians seized the German camp, Irena fled and her family were separated.

"[Her remaining family] went one way and mum went the other way," Mrs Rabbitt said.

Irena was taken in by a German woman and worked on the farm.

Three years later, she was found by American soldiers and told she would be sent to a new country, like England, that would be her new home.

"She must have felt so lonely and frightened," Mrs Rabbitt said.

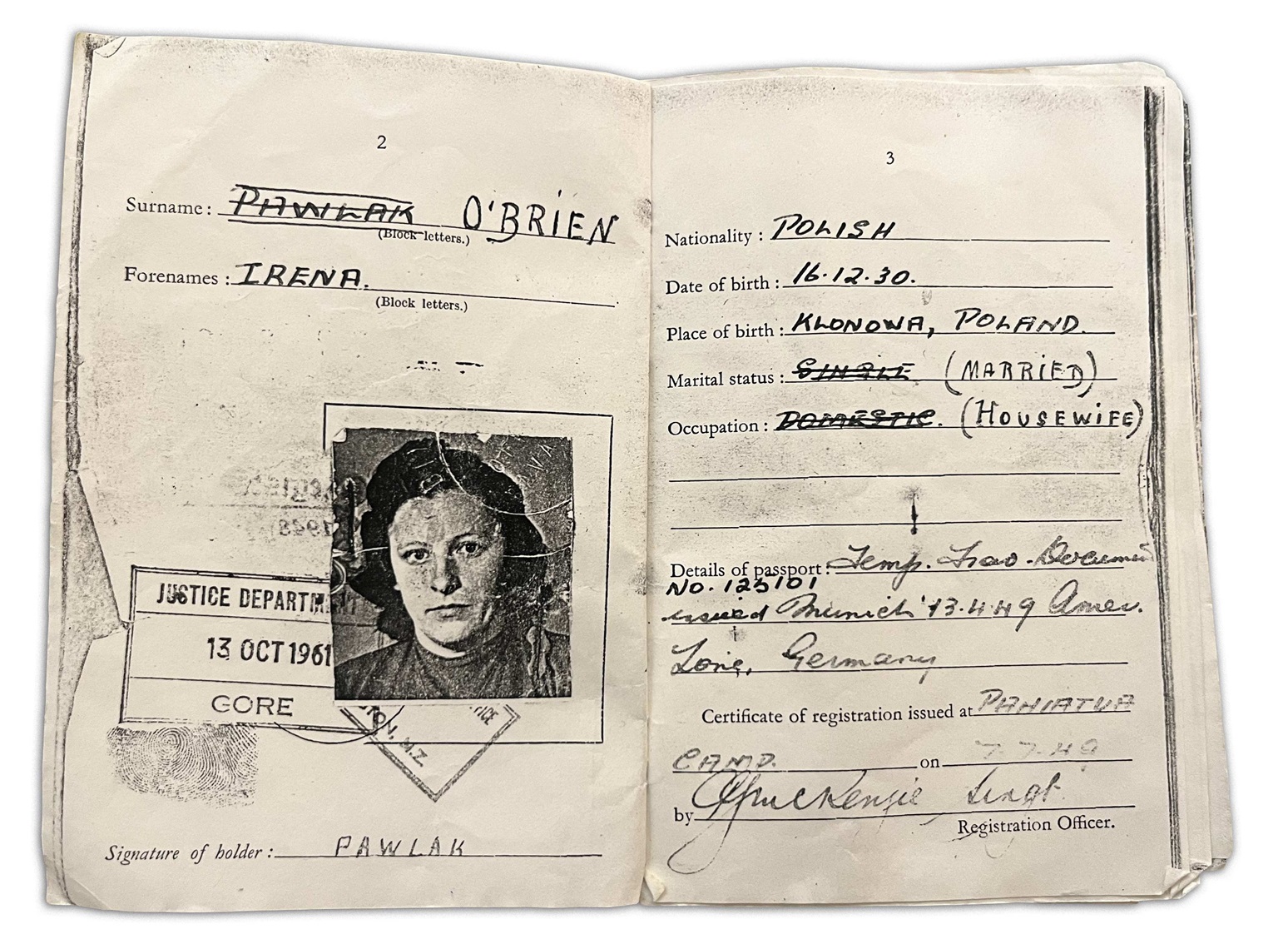

In 1949, at the age of 21, Irena arrived in Wellington and stayed in Camp Pahiatua, which housed more than 700 Polish children.

A few months later she was relocated again, alone, to Gore.

She worked in the Gore Hospital as a domestic in the children's ward, and was taught how to speak English by the nurses and looked after by the nuns.

A few months later, the nurses threw a party for Irena’s birthday and Mr O’Brien was invited.

It turned out they had the same birthday.

A courtship began from there and two years later, they were married and they went on to have eight children together.

Decades on, with the help of the Red Cross, she was able to find a living relative in Poland.

In 1992, Mrs O’Brien received a letter from her brother who had thought she was dead.

Mrs Brumby said the letters back and forth showed the separated siblings trying to piece together their broken memories.

Mrs O’Brien’s brother yearned to see his sister again but due to his difficult financial situation in Poland, he slowly realised this was unlikely.

"He was dying to see her again and you can see how . . . his faith slowly is dropping, thinking, I'm not going to see you, this is too far away," Mrs Brumby said.

Later that decade, Mrs O’Brien lost one of her sons and her husband followed just three days later.

Mrs Swain remembered, after her father’s funeral, she found her mother in what they called "the boys’ room", looking out the window.

"She said, ‘how can I keep my faith?’ and I said, you’ve just got to," Mrs Swain said.

"And she did, she just stuck with it."

After that, Mrs O’Brien disconnected her phone for good, as her daughters said, she could not handle any more bad news.

Mrs O’Brien was strong, both in herself and in her faith, which kept her going.

In her final years, Mrs Rabbitt recalls one of her mother’s carers recognising that strength.

"She had a lot of respect for her, and said she was ‘one tough cookie’."