Painstakingly clipping AstroTurf by hand to form words of protest is just one of the many ways artist Deborah Rundle gets people thinking.

The idea was to emulate the protests of the past where people used weedkiller to form political slogans in grass on prominent hillsides. Only now, using weedkiller is not appropriate, so Rundle had to come up with an alternative.

"It might look simple but it took hours and hours as I had to do [it] by hand, tried to do it by clippers, with a grinder, even hair-trimmers, anything — none of it worked. It just pushed it flat and I needed to pull it up and cut."

She chose to use astroturf to create Then as Tragedy as it comments on the idea of "Astroturfing" of grassroots movements — the process by which local movements are infiltrated or have ideas seeded among them by parties with a different agenda — as well as alluding to the protests outside Parliament, initially against vaccination mandates, which destroyed its lawn.

The words she cut into it are adapted from a Karl Marx quote in relation to repeated events throughout history.

"Yes history repeats first as tragedy then as farce, so I’ve sort of extracted from that to use it for my own purposes, ‘first as tragedy, then as farce’, and I’ve added ‘and tragedy’ as some of the events of contemporary politics can seem entirely farcical and also extraordinarily tragic — the election of Trump, the storming of Capitol Hill."

Rundle’s political focus is reflected in her current interest in "state of emergencies" both real and referencing the root of the word "emerge", meaning to survive and recover from difficulty.

"My ideas are around this time of pause when governments execute the rights to curtail the rights of citizens and only by our co-operation and surrender to that do we all hope that we are working for a greater good."

She looked at the first state of emergency called for political reasons in New Zealand in 1951 in response to the waterfront workers’ dispute.

"I thought that was a very profound moment. Reading about it, about how at that time there were 20,000 workers across the country and their supporters who defied the government and brought about their own "emerging" in terms of a solidarity movement of feeding the workers — you weren’t even allowed to feed the children of the waterside workers."

Rundle likened that to recent restrictions to deal with Covid-19.

"For most people that would be their first experience of their freedom of movement and rights being curtailed in that way. It also provided time for pause, reflection and contemplation about what was going on, the ramification of those events."

The impact of the 1951 event also led her to name the exhibition "Tomorrow is Today Now" after then prime minister Sidney Holland’s statement in a broadcast that unless work resumed "tomorrow, that is today now ... then a proclamation of emergency will be declared".

"It’s sort of a temporal missstep, today is tomorrow now. With the speed at which things are changing now and as we wrestle with our condition, the climate emergency and the swerves we have to take around Covid, today seems to ever be tomorrow now."

Part of the exhibition is a photograph of a plaque in Port Chalmers outside the Maritime Museum commemorating the dispute.

"It uses really interesting language. It talks about the "mauling" of 1951. It’s pretty forthright language to use on a plaque which is usually quite sober. It also uses the expression to reconstruct the future. It’s a bit like ‘tomorrow is today now’, how do you reconstruct the future? It really talks to the things I’m interested in."

Language is a big part of her art practice as she likes to "open up the spaces in language".

"I thought this is great. I like that it kind of trips you up in a way, the same way as ‘tomorrow is today now’."

Her interest in language is likely a reflection of her prior work as a mediator in disputes tribunals. She had always wanted to go to art school but waited until she could afford to, graduating in 2017.

Rundle’s art practice is mostly created in three-dimensional mixed media but first comes the idea.

"I’m driven by ideas and then I think about what media I want to work in. So I’ve got to solve new problems all the time — I don’t want to do much more grass-clipping."

She had to work out how to cut the turf and form the words. After much trial and error, she used an MDF stencil on a board below the turf to help form the words.

To highlight in her work the feelings of searching for equilibrium and finding your footing in the changing times, her work Fact, Fiction, Forecast sits alongside the maritime plaque.

The video was shot by Rundle while sailing as crew on board a yacht from Sydney to Townsville along the Wiradjuri and Murri coastline. On a hand-held camera shooting out a porthole, the shifting horizon is visible.

"It is all very destabilising. With that I was thinking about equilibrium, all the sort of things that play out when you are trying to get a sense of what is going on."

On the other side of the video is an "anchor" styled after a cartoon symbol of an anchor and those seen on maritime workers which is a symbol of connection, commitment and hoping to return home.

"The anchor talks across to the plaque, the industrial dispute of the time and also to what we do to anchor ourselves in community or perspectives, how to take purchase to maintain safe harbour."

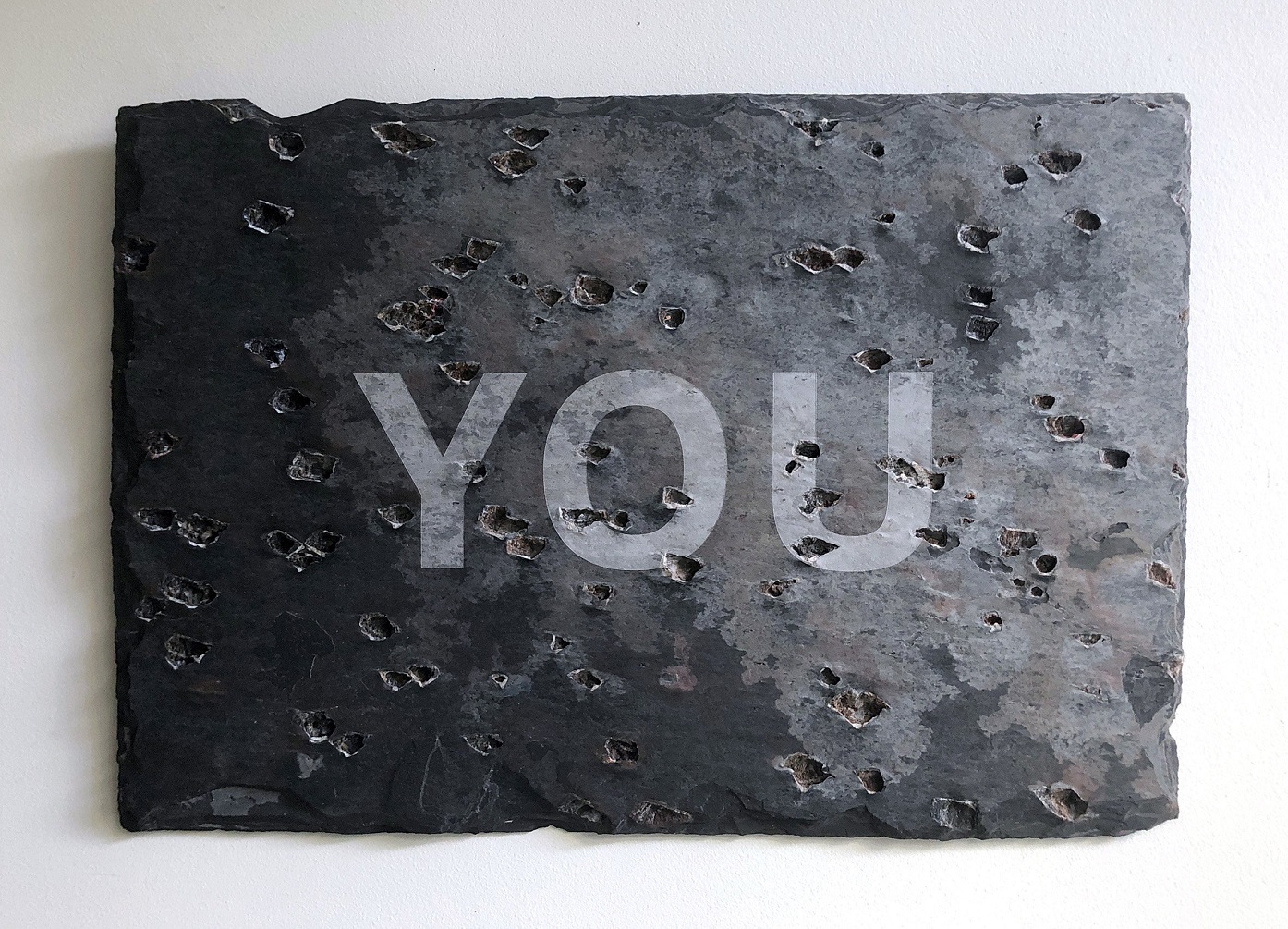

In her other work being shown in Dunedin in the Dunedin Public Art Gallery’s "Nature, danger, revenge" group exhibit, she uses the material and language to get her message across — this time one about body sovereignty and identity as well as the extraction and use of materials from the environment.

She found a box of Chinese slate roof tiles and she etched a word on each slate to read, "On your body still you write my name". The textured surface could emulate the textures of weathered skin.

It was totally coincidental that both shows ended up being on at the same time but meant Rundle had been able to spend a fortnight in the city as she oversaw each show being installed and gave artist talks.

"It has been fantastic for me."

TO SEE

Deborah Rundle "Tomorrow is Today Now" Blue Oyster Art Project Space, until July 30