For some, the head of Lake Wakatipu is a cul-de-sac. At first glance, the mountains that surround Glenorchy in a rough horseshoe offer an imposing signal: "end of the road".

Look a bit closer and a few signposts suggest otherwise.

To others, the area is a starting point for adventures to the west, up and over those peaks or into the valleys that separate them.

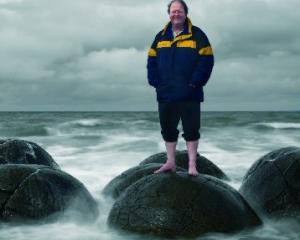

Neville Peat didn't need much of an excuse to explore the Glenorchy-Paradise area in his latest book, High Country Lark: An invitation to Paradise.

Having written several works covering aspects of the area's natural history, the Dunedin author thought it about time he resumed the Lark series he began in 1992.

In his latest, Peat suggests he received an invitation from the mysterious Lark character to venture a good four hours' drive from his Broad Bay home to a place where mystery is as abundant as moss on a beech-forest floor.

It's a clever device, this invitation, for it also lures the reader on a stimulating tramp where birdlife, geology and a host of humans exist in a fragile cohabitation.

Peat believes the head of Lake Wakatipu is the most powerful and scenic mountainscape in New Zealand, "a wonderful balance of mountains, valleys, rivers and lake and islands". He describes the area as a transition zone between Fiordland and Central Otago.

Having collaborated with Brian Patrick on Wild Fiordland and Wild Central (both books were Montana Book Award finalists, in 1997 and 2000 respectively), Peat also penned Land Aspiring: the story of Mount Aspiring National Park in 1994. Thus he had a raft of background material on which to draw for his latest effort.

Yet he wanted to go beyond the "straight-through-the-eyes natural history" and approach nature in a metaphorical, narrative way.

"I'm trying to get to people who are not Forest and Bird necessarily. I'm trying to extend people a little bit.

"I still get feedback on Falcon and the Lark, some 15 or 16 years since it was published," Peat says via phone last week from the North Island, where he has been researching a forthcoming book on the Tasman Sea.

Peat followed Falcon and the Lark (set in the Strath Taieri) with Coasting: the Sea Lion and the Lark in 2001, the latter featuring the sea lion known as "Mum".

The series is special to him; it's a different way of looking at the land, at flora and fauna.

Though each story is self-contained, all feature a man whose idiosyncrasies match the environment through which he wanders.

"The person in the Strath Taieri is a man of the land, a salt-of-the-earth character running around with blade shears in his back pocket, who takes to the air in a hang-glider and goes flying with a falcon he manages to save.

In the sea lion story, he comes down the Taieri River, kayaking and portaging and ends up at Taieri Mouth.

"High Country Lark is a bit different to the previous two as it focuses on trying to describe the environment and some of the historical figures in it. I'm just trying to get people tuned into nature, a mystical sense of it," Peat says.

"Mystical is seeing the whole through a little portion of whatever it is you are studying. It's approaching nature in a metaphorical way, a narrative way. You see quite a bit of writing like this overseas but not a hell of it in New Zealand, except for children's writing . . .

"I think the most powerful writing we can do is to convey a message, not state it. By conveying it we are giving people the power to use their own imagination."

There is a key message in High Country Lark. Implied, rather than stated, it says: cherish this place.

Take a conversation between the Lark and Peat on a peak known as Sugarloaf, which revolves around the nesting habits of New Zealand falcons; the Lark notices a pair have chosen to live at ground level, unlike most of their species; it prompts him to suggest nothing in nature should be taken for granted.

Peat closes the book with suggestions of an earthquake. An image of the Lark entombed in a rock shelter is brought to mind.

Again, the issue of fragility is raised.

"We sit on one of the most geologically active sets of islands in the world," Peat says.

"If we do get a big rupture on the alpine fault - and it is overdue, it could happen any day, really - we will see some tremendous change in the environment."

Human shockwaves are also explored in depth: there is the pilgrimage of coastal Maori in search of pounamu (known as inaka, a strain of greenstone highly prized for its translucent qualities); gold-seekers in the 1860s; the mining of scheelite (a tungsten ore used in weapons, munitions and cutting tools) through the 20th century; high-country wool farmers; and even possum trappers.

More recently, tourism has been added to the list of ways of forging an income.

As evidence of development, Peat points to subdivisions in Glenorchy and the construction of a roundabout that, apparently, many locals prefer to ignore and drive right over. Water-based traditions are also documented.

Steamers plied Lake Wakatipu from 1863; later, the Ben Lomond alternated with the larger Earnslaw until 1951, when the smaller vessel was withdrawn from service. The locals then had two kinds of weekday: boat day and no-boat day.

The opening of the road to Queenstown in 1962, its subsequent tarsealing in the 1990s, combined with reduced depths at the Glenorchy wharf caused by the steady accumulation of sediment from the Rees and Dart rivers (the latter had a peak flow of 2200cumecs in January, 1994) have meant the Earnslaw is no longer needed nor practical in the northern arm of the lake.

Horses have always been a popular form of transport in the area. According to Peat, horses still outnumber people up that way. Growing out of the tradition of gymkhanas, the Glenorchy Races remain an annual event, attracting locals and visitors alike.

• Peat believes cul-de-sacs often collect characters. And, in that regard, the Glenorchy-Paradise area doesn't disappoint.

He presents a range of interesting personalities over the years, from Arcadia House's mysterious owner, Joseph Fenn, to Bill O'Leary, better known as Arawata Bill, who, despite being named after a South Westland river, had strong connections with the area at the head of Lake Wakatipu.

Yet perhaps one of the most interesting inhabitants of the region is (or was) the South Island kokako.

The Department of Conservation proclaimed the species extinct in January 2007, when it published its triennial review of the status of New Zealand flora and fauna, a position supported by the Ornithological Society of New Zealand.

However, Peat contends otherwise, citing a range of presumed sightings and hearings of the bird's distinctive call.

"Doomed? Maybe. Extinct? Not yet," he writes. (See link with extract.) Peat uses the South Island kokako to express the mystery of the area.

"Those mountains and valleys . . . are likely to reveal life-forms that are quite improbable," he says.

"One of the ones I do discuss in there is the rock wren and how delicate that looks. The South Island kokako is kind of a larger version of that delicate and vulnerable bird . . . People are still looking for them. We occasionally get reports of very piercing and riveting bird calls."

Peat was elected to the Otago Regional Council in 1998; in 2007 he was appointed deputy chairman as well as leading the council's environment and science committee.

Though he has recently stepped down from the ORC, his interest in sustainability issues remains strong.

"Although people see me as a conservationist in the sense of vigorously protecting nature, I'm as much a sustainable management person. I guess that's why I had an interest in the regional council.

"We need our totally protected areas but, more than anything, humanity needs to be espousing a sustainable approach," he says, pointing out that those who farm at the head of Lake Wakatipu know best what's required to maintain their environment.

Peat quit the ORC to concentrate on writing High Country Lark and the larger Tasman Sea project.

A 2007 Creative New Zealand Michael King Writers' Fellowship, at $100,000 the country's largest literary award, has helped cover expenses, particularly in relation to Peat's research into the Tasman.

"It is like a biography of an ocean," Peat says, "looking at natural process, currents, water masses and the underlying geology. Then I'll get into the human side. It's quite big in scope."

Peat has had a long interest in shipping and the sea. After entering journalism at the Evening Star in 1965, he got his first overseas job as a shipping writer in Cape Town.

At the time, the Suez Canal was closed; "everything came around the Cape of Good Hope"; it made for interesting times.

Peat has been writing books for more than 25 years; he has more than 30 to his name. At 60, with more ideas in the pipeline, he says it's not a bad life.

"I think as a writer you've got to be diversified. It's very hard to make a living without fellowship grants or without support of some sort. To vary it a bit, I do expeditions on a small study ship around New Zealand. I also do things like museum exhibitions."

Regardless of the sideline work, words remain at the heart of Peat's world. They beckon like birdsong from the bush.

"I still believe in the power of the printed word over visual stuff. In the end if you want to change hearts and minds . . ."

Fact file

High Country Lark: An invitation to Paradise

by Neville Peat

Longacre Press

pbk, $45.

• Neville Peat (60) lives at Broad Bay, on the Otago Peninsula, with his wife, Mary, and daughter, Sophie.

• Born in Dunedin, he has worked as a journalist and an information officer with the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research's Antarctic Division. He has been writing full-time since 1986 and has published more than 40 titles.

These include regional natural histories and New Zealand guides, histories of the Antarctic, and studies of birds, especially those indigenous to New Zealand.

• His book, Wild Dunedin: Enjoying the Natural History of New Zealand's Wildlife Capital, with Brian Patrick, won the Natural Heritage category at the 1996 Montana New Zealand Book Awards.

Wild Fiordland: Discovering the Natural History of a World Heritage Area, also with Brian Patrick, was short-listed for the same prize in 1997.

• In 1994, Mr Peat was named the inaugural Dunedin Citizen of the Year for a series of books on Dunedin as well as the establishment of the Dunedin Environmental Business Network in 1993 and other environmental initiatives.