Rebecca Fox asks Ryan a few questions about what he discovered.

What was Otago and Southland’s role in the history of New Zealand beer - apart from being the site of the first beer brewed in New Zealand?

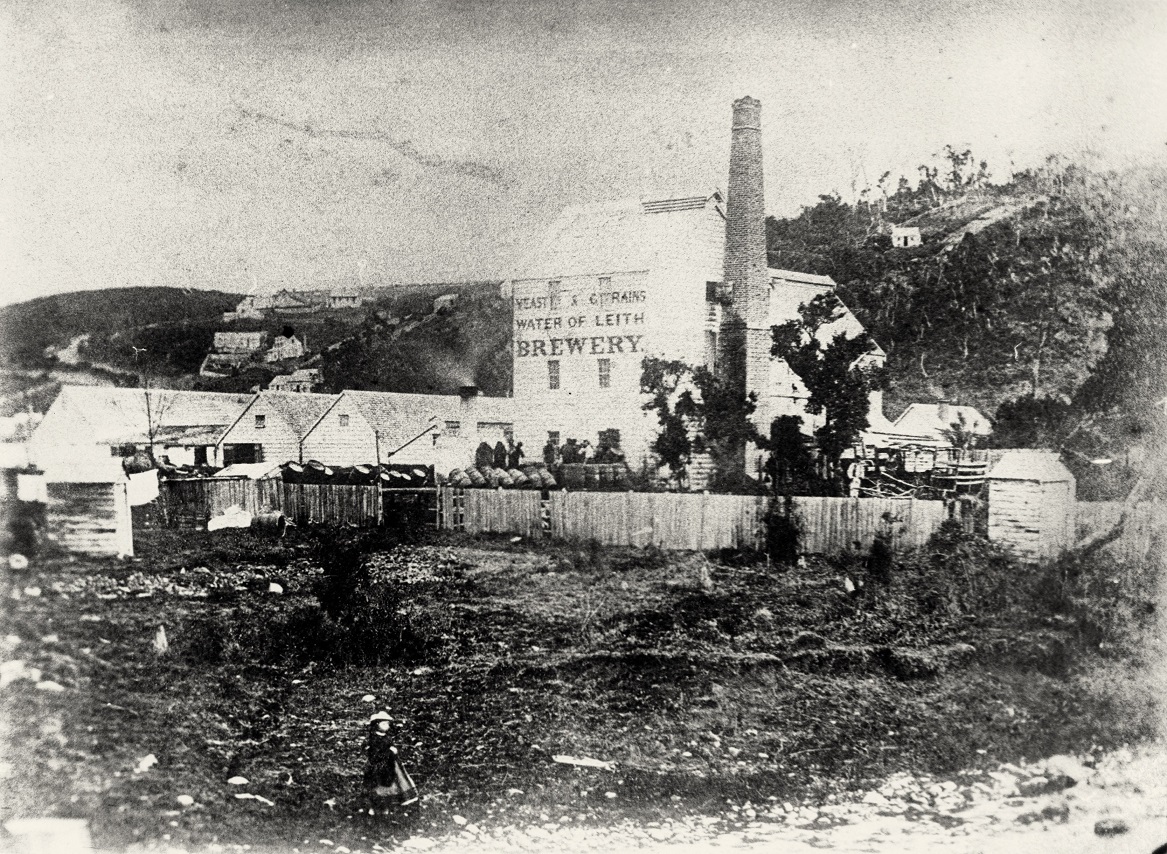

Following the gold discoveries of the early 1860s Otago dominated New Zealand brewing for the remainder of the 19th century. It had a quarter of all breweries in New Zealand and produced 40% of all beer during the 1870s.

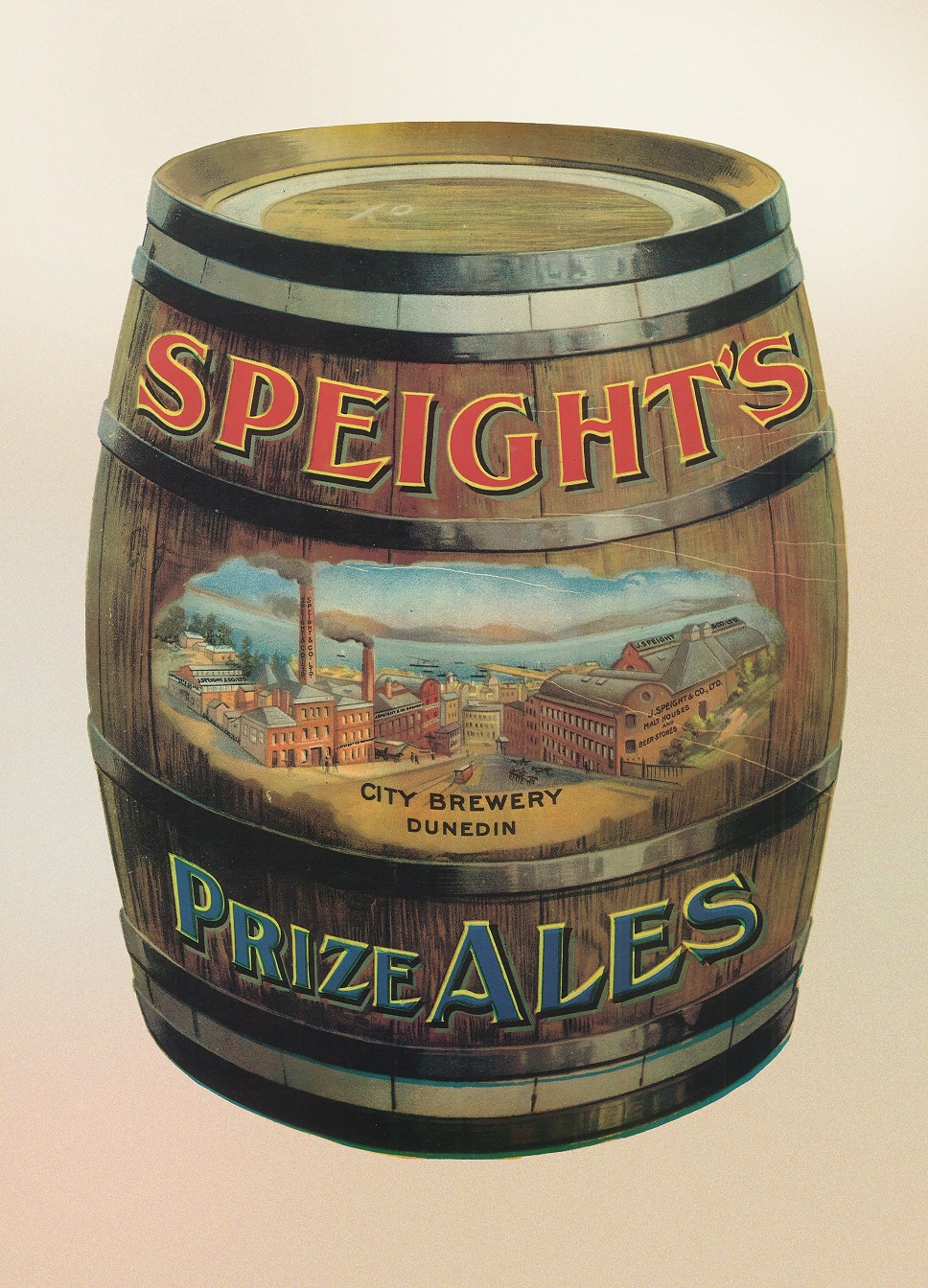

By the 20th century, Speight’s was one of the dominant breweries in the country and its management were key players in both campaigns to resist the prohibitionist movement against alcohol and in the merger that created New Zealand Breweries (later Lion) in 1923.

What was the most surprising thing you learnt in researching this book?

There were many surprises, but perhaps the oddest was that when the two big breweries started delivering beer to pubs via tankers during the 1950s, there were several instances of the tankers crashing and local people turning up with every bucket or other container they could get hold of to scavenge the beer. In Taranaki, one local apparently filled his bath with beer after one of these crashes.

Any little-known interesting stories around Speight’s or brewing in Otago?

The main thing for me is that if you look at who was the most influential person in the Speight’s partnership, I think the company should really have been called Dawson’s. William Dawson was the head brewer and very much responsible for the reputation that Speight’s acquired for producing a sweet, strong beer that was quite different from a lot of the lighter styles around the country. He particularly liked to brew different kinds of stout with additives such as juniper berries and treacle.

Dawson was mayor of Dunedin in 1887 and an MP 1890-93. But he got in trouble with two later mayoral campaigns in 1884 and 1901 when the Customs Department objected to free beer being provided from the brewery on the day of the election - clearly trying to influence voters.

In his book, Ryan goes on to say "arguably the most talented brewer attracted to New Zealand was William Dawson.

"Born in Aberdeen and learning brewing under the tuition of his father in Durham, he worked briefly in Burton-on-Trent and then for William Younger & Co in Edinburgh before reaching Dunedin in July 1873 and beginning work at the Well Park Brewery. Three years later with fellow Well Park employees James Speight, a traveller for the brewery, and Charles Greenslade, a miller and maltster, he left to establish the City Brewery, more commonly known as Speight’s.

"William Dawson sen joined them as a brewer in 1879.

"Despite the trading name of the firm, which was entrenched as one of New Zealand’s leading breweries by the late 1880s, Dawson, as head brewer, in many ways contributed most to the character and reputation of the beer.

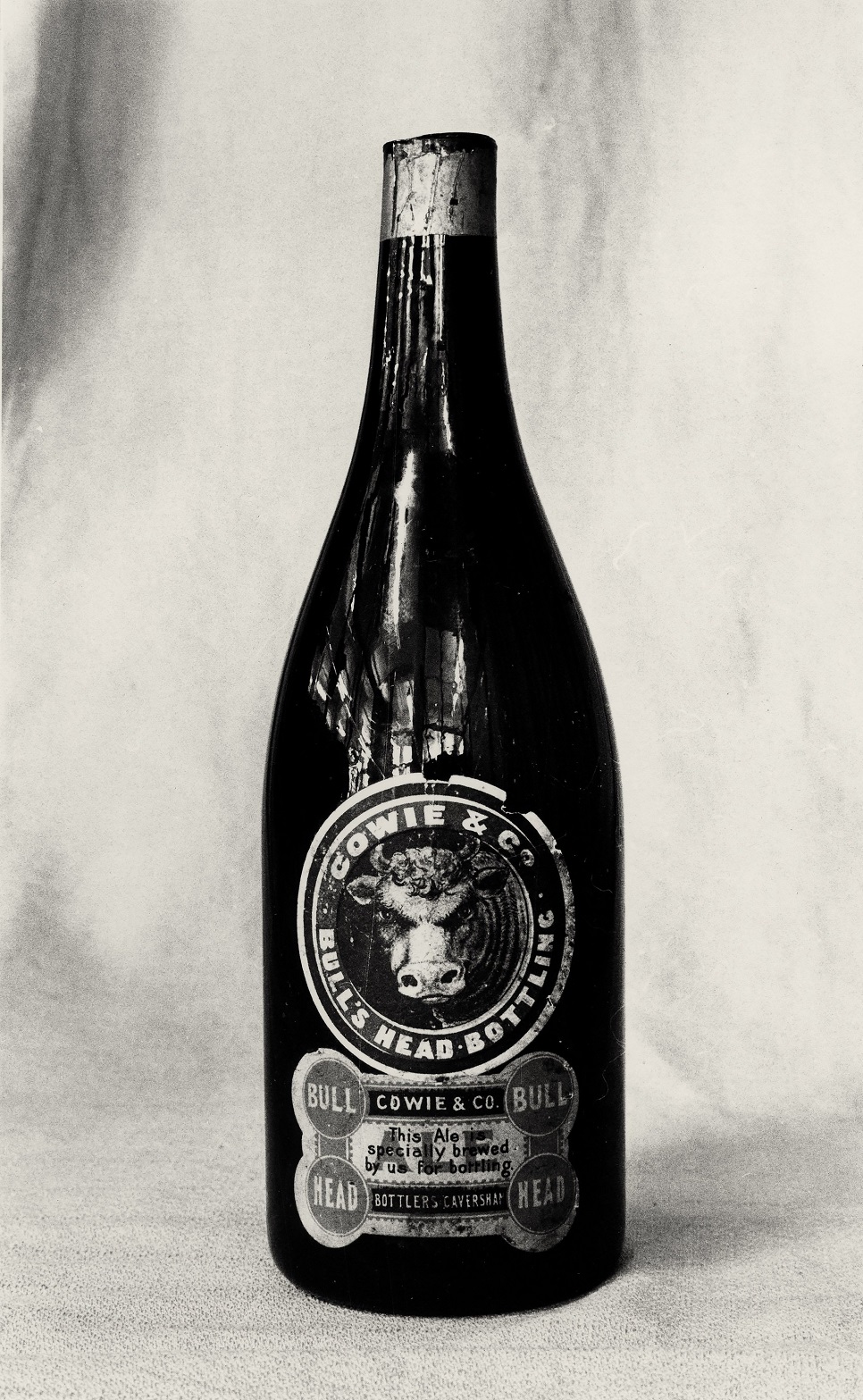

"An examination of the Speight’s brewing book from 1879 to 1891 reveals production of nothing less than XXX ale and increasing amounts of XXXX ale, strong ale, stout and various ‘special’ beers as the decade progressed. Dawson was constantly experimenting with new techniques and ingredients, and was a particularly enthusiastic brewer of stout. One recipe included gentian root, juniper berries and treacle. He also used liquorice and wheatmeal.

"Journalist and idiosyncratic beer historian Pat Lawlor, in his Froth-Blowers’ Manual, makes it clear that early 20th-century New Zealand was firmly divided into two camps based around liking or loathing of Speight’s.

"Of his first encounter sometime before 1910 with what he described as a ‘stern and solid’ beer and a ‘beer of integrity’, he noted that his initial grimace and dislike of the high alcoholic content prompted the barmaid to suggest that in future he have it as a shandy."

Like most students, I quaffed my way through what the two big breweries had to offer during the 1980s - although I did have a couple of friends who noticed Mac’s ale when it first reached Christchurch in the early ’80s.

Throughout the ’90s, I was a Guinness drinker if I wanted something different.

The real transformation for me was a trip to Belgium in 2002 where I discovered an extraordinary variety of local beer - each served in its own unique glass. Nobody was quaffing jugs. People were having beer with dinner and clearly thinking about what they were drinking/how and where it was produced. It was very much like a good wine culture.

As a New Zealand historian with some awareness of the campaigns to restrict alcohol in New Zealand, and of things like the swill, I began to wonder why Belgium had the beer culture it had and New Zealand had what it had - remembering that in 2002 we had certainly had about 15-20 years of some new small breweries producing interesting beer, but nothing like what has developed over the last two decades.

The answer to my question is that in Belgium beer has always been part of sociability. In New Zealand, we had a succession of political and moral campaigns to ban it - led by people who imagined that a fresh start in a new world society like New Zealand would be best without any alcohol. The solutions they created tended to divorce alcohol, and beer especially, from normal socialising. For example, legislation passed in 1910 effectively capped the number of pubs in the country.

Over the next 40 years, as the population increased, the pubs that existed inevitably became more crowded and unpleasant and they weren’t well distributed - lots on the West Coast but very few in Hamilton.

Weak beer served in dilapidated and overcrowded pubs does not make for a nice, social drinking environment.

The two big ones for me in New Zealand are 1880 and 1942.

In 1880, the government first introduced excise tax on beer.

From that point the whole business of brewing became much more bureaucratic - with Customs inspectors monitoring breweries and an increasing labyrinth of regulations. Eighteen-eighty also set the pattern where governments regarded beer tax as a good source of revenue - so that in tough economic times they tended to increase the tax rate with the result that brewers and then publicans increased the price of beer to consumers.

That approach encouraged big breweries - who could absorb the tax increases more easily than smaller ones.

Nineteen-forty-two was when the government, as a wartime efficiency measure, legislated that the maximum strength of beer could be no more than about 3.8% alcohol by volume.

Previously, most beer had been around 5-6%. This had an immediate impact on Speight’s.

They had sent their strong beer all over the country. But they could now only produce weaker beer - which wasn’t as durable and didn’t travel well.

They retreated to being very much a local Otago/Southland brewery. The large-scale production of weaker beer suited the bigger breweries and helped to squeeze out the last of the small breweries to the point where we only had DB and Lion in the market by 1970.

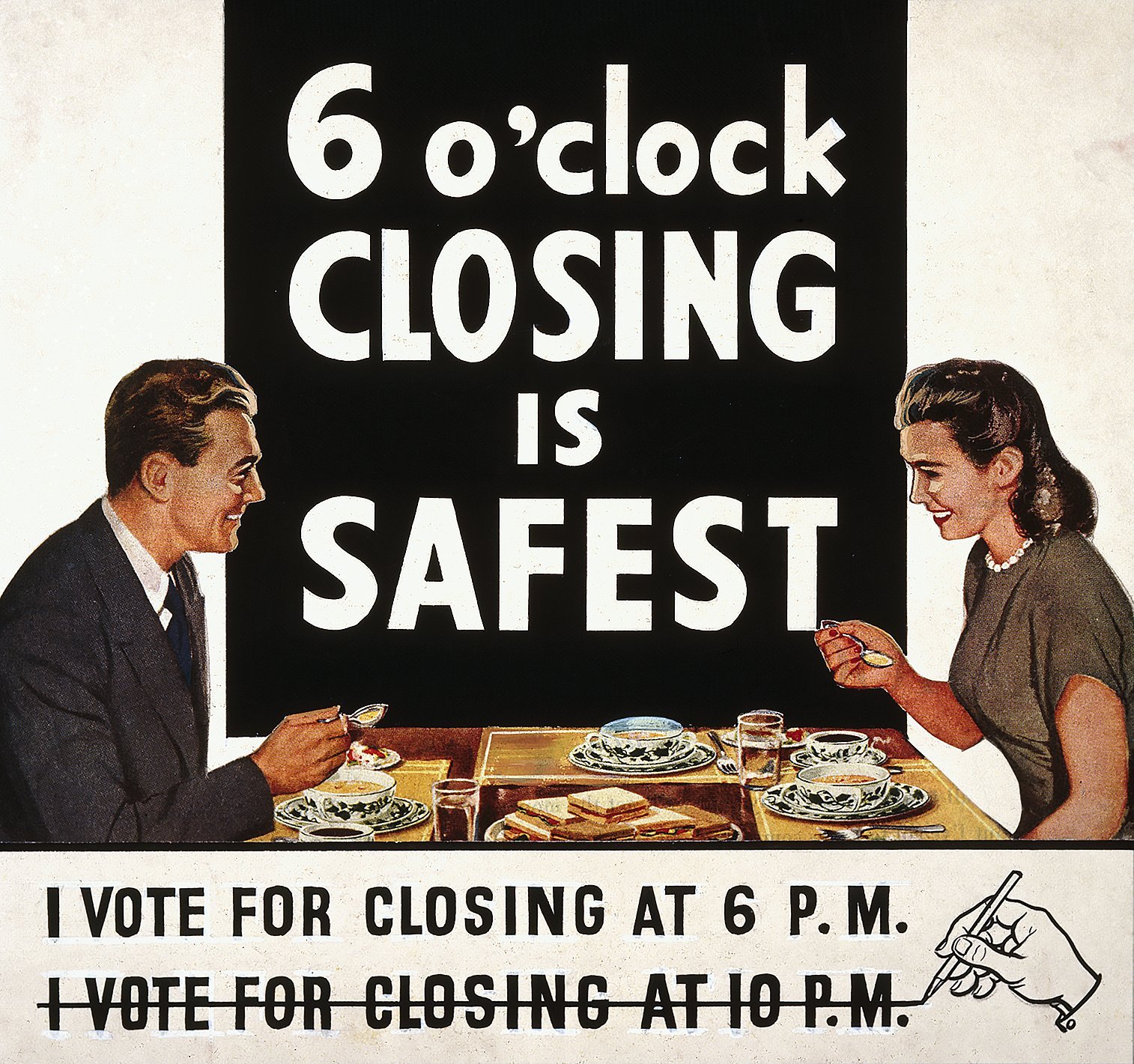

The other thing with 1942 is people started drinking more weak beer to get the same alcohol effect enjoyed previously. Drinking more beer quickly, and remembering the pubs closed at 6pm, also produced what became known as the 6 o’clock swill that lasted until 10pm closing was allowed in 1967.

How have Kiwis’ drinking habits changed, do you think?

In some respects, we have come full circle. During the 19th century, people tended to drink different beers from local breweries. The rise of the two big breweries then produced very homogenous beer styles, where everyone was drinking a very similar sort of sweetish and slightly flat amber lager - usually served too cold. Now, with many more breweries and beer styles again, and with imported beer, the beer consumer has more to choose from.

As a consequence of guzzling weak beer, and of various misguided attempts to restrict the way pubs operated (more on that below), we had a period where beer drinking was almost a sport in its own right, with quantity more than quality - quite separate from enjoying it with food or in a relaxed social setting where you may actually ponder the style and taste of what you’re drinking.

We have gradually got back to the point where beer drinking is more a normal part of socialising. Of course, we still have some issues with young people guzzling cheap beer. But the fact that New Zealand’s per capita beer consumption was once in the global top 5 and we are now 27th confirms that the emphasis has shifted to quality above quantity.

What can we learn from the history of beer going forward?

It is important to remember that beer is only one part of alcohol - by which I mean that debates in New Zealand about an "alcohol problem" need to be a lot more targeted in terms of who is drinking what and where - and solutions need to address those differences.

The country’s first temperance society, formed in the Bay of Islands in 1836, was opposed to spirits - but not wine or beer. During the 19th century, there was much emphasis in New Zealand on beer as a healthy alternative to spirits. Fast-forward to the 21st century and we have references to an "alcohol" problem, whereas the one very significant change to New Zealand alcohol consumption patterns over the last two decades has been the rise of RTDs. Consumption of mainstream beer has declined significantly. Hence, we need targeted responses to alcohol issues and not sweeping generalisations.

It frustrates me when people suggest blanket solutions - such as "let’s put a 50% tax increase on beer to raise the price and reduce consumption". If you do that, then the big businesses are in a much better position to absorb such costs and remain competitive than the small players are - so it would take us back to the days of the big brewery duopoly. As some craft brewers have pointed out, it’s not their bottles that are being thrown down the street after Dunedin student parties! So again, any discussion of alcohol issues, and the place of beer within them, needs to be nuanced.

Could climate change have a serious impact on New Zealand beer habits?

Beer, as with any alcoholic drink, is based on raw materials - in this case mainly barley and hops. If growing conditions change or if extreme weather patterns cause more damage to crops, then inevitably we will have a scarcity of raw materials. Scarcity will push the price of beer up. But we live in hope that science - both of climate and brewing - will find solutions to mitigate problems.

Barley, hops, etc and be developed with more tolerance to extreme conditions. Higher yields from crops will also help, with less space required to produce what is needed. Or perhaps someone will just develop a chemical that looks and tastes like beer!

What drove you to write the book?

How long did it take?

From when I had the first thoughts about this in May 2002 until now is 21 years - far too long. But in my defence (yes, I do get defensive with various friends who have wondered whether this book would ever materialise) I got sidetracked into Lincoln University senior management for more than a decade and also wrote another book - Sport and the New Zealanders - along the way. I wrote a rough draft of the first half of Continuous Ferment in 2009 and then made virtually no progress for another decade. I rewrote the first half in 2019 and continued on mainly during 2021 and 2022.

In some ways, I don’t regret taking this long. The New Zealand beer scene has changed a lot since I started.

This was going to be a 10-chapter book, but became 11. Watching how beer consumption has changed in New Zealand and around the world this century has certainly sharpened some of my thinking about the history and what I wanted to know.

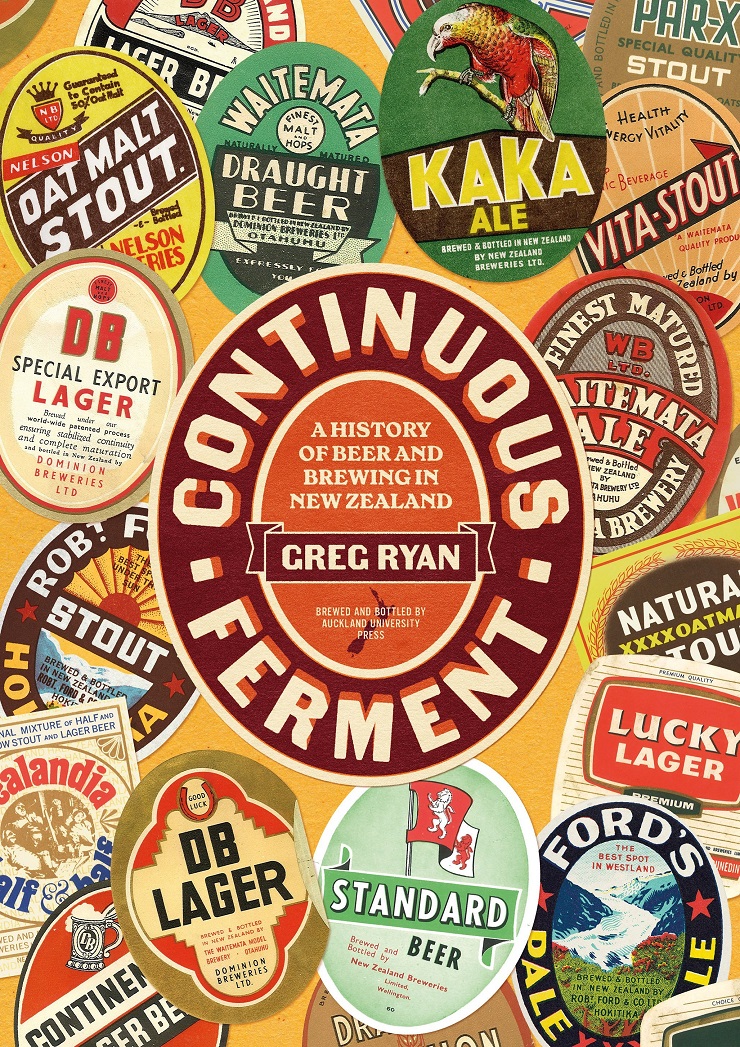

The Book

Continuous Ferment, by Greg Ryan (Auckland University Press, RRP$65).