The Victorian painting had just been gifted to the Dunedin Public Art Gallery by the National Collections Fund, London, facilitated by the Dunedin Art Gallery Society.

Watts had only died 30 years earlier, and collectors, both public and private, were vying for artworks made by "England’s Michelangelo" — the illustrious moniker given to the artist.

It was an impressive addition to Ōtepoti Dunedin’s art collection.

The newspaper reported Governor-General Lord Charles Bledisloe had said, "there was something extraordinary about the face in this portrait which should be both inspiring and suggestive".

Watts’ self-portrait is at present on display in the exhibition "Paradise of Imagination: Medieval & Modern Encounters", at Dunedin Public Art Gallery, where it inspires and suggests an imaginative medieval realm through the figure of the knight.

Knights are among the most iconic images associated with medieval culture.

Nineteenth-century Britain underwent a revival of interest in the visual arts, literature and history of the Middle Ages (or medieval period, which roughly dates from 500 to 1500).

Throughout his artistic career, Watts continued to depict knights and other subjects drawn from this historical context.

His friend, the Victorian poet laureate Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892), was similarly inspired by chivalric tales, such as those relating to King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table.

For instance, both the poet and the artist represented Sir Galahad from Arthurian literature — although Watts emphasised that his painting was "not an illustration to accompany the poem [published in 1842] and was painted before he saw the poem".

Originality was clearly important to Watts, who declared, "I paint ideas, not things".

Eve of Peace reflects this interest in allegory through its sombre tone and symbolism.

The peacock feather was added later and is a symbol with several meanings.

Combined with the downcast gaze, the presence of the feather suggests that the knight is not concerned with earthly quests but is contemplating the implications of his own mortality.

Where there are knights, there are often dragons.

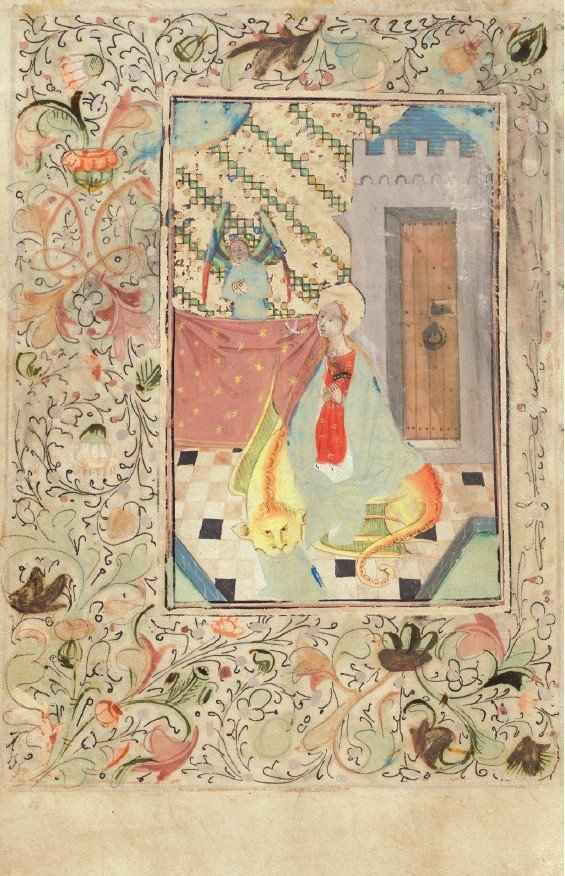

However, in "Paradise of Imagination", it is a female saint, not a male knight, who defeats the dragon.

St Margaret emerges from the belly of a dragon in a page of a 15th-century book of hours (a simplified prayer book with hourly devotions and readings for the non-ordained).

This is the Fitzherbert Book of Hours in the Alfred and Isabel Reed Collection of the Dunedin Public Library.

Margaret was believed to have been from Antioch, in modern-day Turkey, born towards the end of the third century.

She refused marriage and the order to abandon her Christian faith and pledge of chastity, resulting in torture and imprisonment.

While imprisoned, she encountered Satan in the form of a dragon, who swallowed her, but her faith enabled her to remain unharmed.

The serpentine dragon recalls Satan’s disguise in the Garden of Eden, as dragons were often described as types of serpents in medieval bestiaries (encyclopaedic-like texts about animals and mythical beasts).

Like Watts’ knight, the story of St Margaret inspires and suggests themes within and beyond the medieval imagination.

Margaret undergoes a trial, much like a knightly quest, which ultimately results in her securing a place in the heavenly afterlife.

Watts’ self-portrait echoes the introspective nature encouraged and facilitated by books of hours, whereby medieval readers could engage with their faith in a personal and intimate way.

Both Eve of Peace and St Margaret showcase the intriguing traces of the medieval past found in Ōtepoti’s art and heritage collections and are on display until February 8.

Anya Samarasinghe is a curatorial intern at Dunedin Public Art Gallery.

![‘‘Neil’s Dandelion Coffee’’. [1910s-1930s?]. EPH-0179-HD-A/167, EPHEMERA COLLECTION, HOCKEN...](https://www.odt.co.nz/sites/default/files/styles/odt_landscape_small_related_stories/public/slideshow/node-3436487/2025/09/neils_dandelion_coffee.jpg?itok=fL42xLQ3)