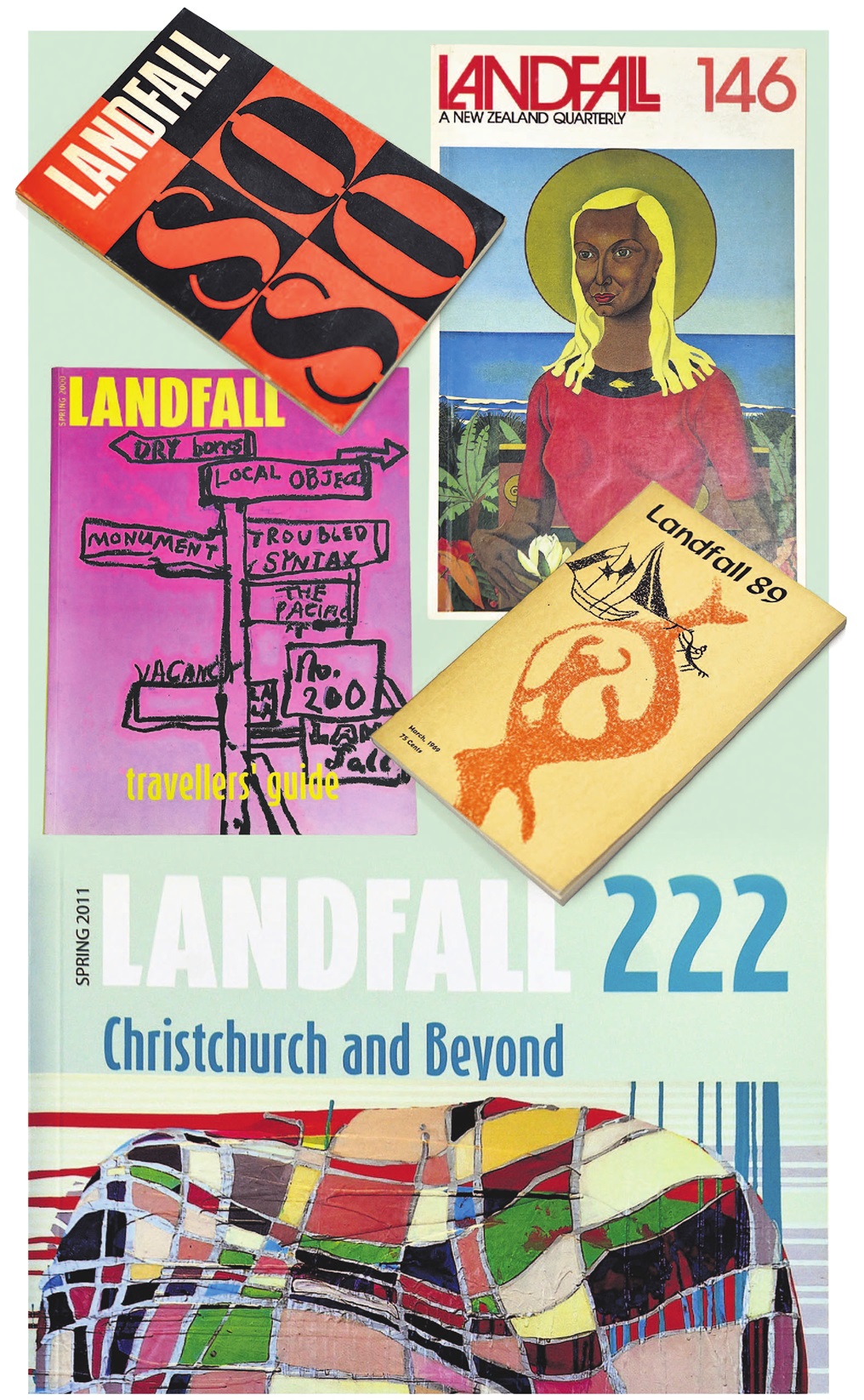

The first thing you notice upon entering Otago University Press’ Castle St villa is the large bookcase on the right. It’s chock-full of Landfall editions in all their glorious incarnations.

Indeed, the collection and its bookcase present as a vital structural component bracing the walls of the publisher’s offices.

The magazines also look very tempting, lined up like soldiers on a literary parade ground.

"Touch one. Go on, take one out," a voice inside says. I resist, not wanting to be responsible for damaging something priceless.

But then Otago University Press publisher Dr Sue Wootton comes out of her office: "Here, have a look," she says, diving into the bookcase and passing over a copy of the very first issue. After opening it, the cover comes off in my hand.

"Don’t worry, there’s more copies of that one around," she says reassuringly.

Wootton is well aware of the significance of the bookcase.

"The voices in there," she says. "The energy, the spirit, the vision, the life-blood that connects them all. This is a living thing, this kupu-creature with ink in its veins and its array of multi-coloured spines."

Landfall has just added another spine, olive green for its 250th edition, and its publishers have taken the opportunity to change its name to Landfall Tauraka, a move editor Dr Lynley Edmeades says embraces its founding principles and its contemporary kaupapa as a "vibrant gathering space for the broad spectrum of imaginative work being made in Aotearoa".

Landfall, a foundation for New Zealand’s writing talent since March 1947, is inextricably linked with Dunedin and is an enduring jewel in Dunedin’s Unesco City of Literature crown. Its relationship with the city goes right back to its founding editor, poet Charles Brasch, who continued editing the review until 1966.

In the past 78 years, Landfall has published more than 8820 contributions of New Zealand poetry, fiction, essays, art, criticism and reviews. There have been 2566 contributors.

It has paved the way for, and solidified, many literary careers, including those of Brasch himself, CK Stead, Ngaio Marsh, Elizabeth Smither, James K Baxter, Witi Ihimaera, Paula Morris, Allen Curnow, Denis Glover, Frank Sargeson, Vincent O’Sullivan, Patricia Grace, Fiona Kidman, Gregory O’Brien, Hinemoa Baker, Eleanor Catton and Xiaole Zhan.

Among the artists whose work has been featured are Colin McCahon, Ralph Hotere, Rita Angus, Ann Shelton, Kate van der Drift, Grahame Sydney, Tony Fomison, Michael Smither, Lorene Taurerewa, Thelma Kent, Anthony Stone, Saskia Leek, Marilyn Webb, Tia Ranginui and Fiona Pardington.

The 250th edition of the twice-a-year journal was published slightly earlier than usual to coincide with the Dunedin Writers and Readers Festival, last weekend.

An accompanying exhibition, "Landfall Tauraka: 250 issues of new writing, art and ideas", is now open in the de Beer Gallery, Special Collections, on the first floor of the University of Otago Central Library.

Otago University Press began publishing Landfall in 1995 (issue 189), after a long stint by The Caxton Press, until 1992, and a shorter one by Oxford University Press.

In the publisher’s note at the start of that issue, Wendy Harrex says:

"Welcome, thrice welcome to Landfall, the wandering journal returning to its home. Founded in 1947 by Charles Brasch, Dunedin citizen and benefactor, Landfall was produced from his home in Heriot Row and later (1962 to 1966) from what is now the staff tearoom of the University Book Shop, Dunedin. Ruth Dallas, who worked with Brasch on Landfall, has a chapter on those years in her autobiography, Curved Horizon.

"Anyway, Landfall is back in Dunedin. And we at the University of Otago Press feel rather like Thelma Kent’s dog on this issue’s cover, sticking our neck out as its publisher. So welcome us, too, as we nurture this journal heading for its fiftieth anniversary ..."

Dr Wootton says it is impossible not to be mindful of the importance of Landfall.

"I took this job on a few years ago and then it dawned on me — I could see it coming; we were only seven issues away from 250, and that’s quite major.

"There’s never been a New Zealand journal that’s had this longevity."

Atop that bookcase full of Landfall magazines, there’s a framed photograph of Brasch. He holds a special place in the heart of New Zealand’s and Dunedin’s arts community. His philanthropy launched Otago University’s Robert Burns Fellowship, the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship and the Mozart Fellowship.

"He would be really thrilled to see that Landfall is still going and the kinds of work that we publish in it. It’s interesting, because people often look back and think ‘oh, it must be very conservative’, but you’ve got to be careful that you’re not judging 1947 by 2025 standards.

"In fact, it’s always been, in its moment, quite a progressive, open, boundary-pushing platform. And it’s easy to forget that, because what that looked like in 1947 is different to what it looks like now. But if this hadn’t been started in 1947, we wouldn’t be publishing the range of voices that we now publish.

"These first issues, these first years, they're very focused on what it means to be a New Zealand writer. Of course, it's immediately post-war, so the writers are mainly Pākehā men.

"And it’s a social critiquing role too — whether you know that it is or not while you're doing it — because you can't help but be the product of your society and your cultural norms, and many artists are kicking out against [that] — ‘well, why is this a cultural norm? Why can't it be this?’."

The acceptance of voices other than white males in Landfall changed "reasonably quickly", Wootton says.

"The move toward a more balanced representation in Landfall from women and Māori, along with other traditionally less empowered demographic ethnic, gender or ability groups, occurs in parallel with socio-political changes in Aotearoa New Zealand, with a flowering from the 1970s-on of creative work arising from the Māori renaissance and from progressive social movements such as feminist activism.

"But, of course, some of the older guard were reluctant to allow that these new emerging voices should be granted any legitimacy — by which was meant legitimacy within the traditional Western literary canon, which by definition mainly included works by men working within Anglo or European cultural traditions."

She provides two examples of misogynistic reviews.

In December 1971, Fleur Adcock’s High Tide in the Garden was reviewed by CK Stead.

"Fleur Adcock’s poems suggest not only a woman’s sensibility and preoccupations but a woman’s voice — as distinctly as handwriting can suggest a female hand. She is (if I can speak loosely for the fraternity) better than most of us. She always writes well. She seems gifted with that slightly detached female intelligence that can martial even the most wayward feelings and make verbal sense and shape of them. But her poetic virtues are also her poetic limitations. She lacks the will, the passion, the ebullience, buoyancy, egotism on which great or strongly original structures are flung up."

In December 1980, Fiona Kidman’s A Breed of Women was critiqued by WS Broughton.

"In this novel we are at least spared the frenzy that keeps rasping in the polemic of a novel such as The Women’s Room; but the bland alternative of A Breed of Women isn’t much preferable. Perhaps what is really irritating about A Breed of Women is that it pretends to be a novel in the vogue of modern feminist writing, but it reads like a thinking woman’s Mills and Boon."

Wootton has analysed the changing gender divide.

Landfall 109 in 1973 listed five women out of 18 writers, reviewers and artists; Landfall 147 in 1983 had 29 contributors, 10 women; while Landfall 249 in May had 61 contributors, 41 of them women.

"Some might say that the rebalancing has gone too far the other way," she says.

But despite that, there is still only one woman in the 10-most-published-in-Landfall list — Elizabeth Smither, who was first published in Landfall in March 1974 with a poem called Goldfish.

Her most recent poem, Learning from Emma, appears in Landfall Tauraka issue 250.

Poet and creative writer Edmeades, a lecturer in the English and linguistics programme at the university, took over as editor from issue 242 in late 2021.

In an article on the university’s website at the time, she said she was "decidedly nervous" she might find the editor’s job overwhelming, but instead had discovered it was a pleasant experience which she enjoyed.

"I went pretty slowly through everything, and was so intrigued as to what I might find in the pile of submissions," she said then.

That sense of surprise and wonder remains.

"Certainly, for those first couple of issues I was quite anxious, reading and re-reading, making sure I hadn’t missed anything. But now I’ve gotten a lot more efficient.

"I have complete autonomy, I know — it’s actually amazing, it’s scary. In those first few issues, it was like, ‘how do I decide? What do I like?’ And then as time’s gone on, I’ve just trusted my opinions more and my instincts more. Occasionally I’ll say to Sue: ‘Can you have a look at this? Is this really good or really bad?’

"I think a lot about representation, making sure when I’m going through I have my yeses, usually quite a small pile, and I have a big pile of maybes. Once I’ve got the yeses there, I’ll look through the maybes for who’s missing, and what kind of writers we need to be representing who are already in that pile."

So, what would clearly be a "no" in her eyes? She answers in terms of what would make a "yes".

"I’m looking for control — if I feel like the writer has control of the page, the line of the sentence, of the vocabulary. Also for something surprising — if it’s not where I was expecting it to go, if it’s a strange subject that I haven’t read about before. Or some interesting juxtaposition — so it might be really formal, like a formal sonnet, but about something really contemporary. So that’s, I guess, another surprise element.

"You know that there’s going to be a lot of good work that doesn’t fit in every issue."

Edmeades has introduced a craft interview series, to delve into what Landfall means to its writers. In the first issue of Landfall Tauraka, she chats with former poet laureate and founder of the International Institute of Modern Letters at Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington, Bill Manhire.

There’s more than words in any one issue, though, with each featuring two commissioned art portfolios. Edmeades is considering changing this.

"I’d like to make one of them for an emerging artist. We don’t run a competition, but we could for the emerging artist open it up so people send in their portfolios and we get to choose, just to make it less work and a bit easier to find them."

The de Beer Gallery exhibition celebrates Landfall as an art form.

Exhibition lead curator Kirstie Ross, the university’s head curator of published and special collections, says the journal has been "both an agent provocateur and a safe harbour for Aotearoa’s writers, artists and thinkers for almost 70 years".

The exhibition highlights the "significant cultural and publishing achievement" of the country’s longest-running literary and arts journal.

"While curating the exhibition, I’ve enjoyed reading unique archival items that show how the idea and reality of Landfall evolved — for example, re-reading Brasch’s diaries during the journal’s formative years and stumbling upon some juicy correspondence written by famed short-story author Frank Sargeson related to the judging of Landfall’s first poetry award held in 1953."

The first issue of Landfall Tauraka includes three commissioned essays from different generations of New Zealand writers.

Edmeades invited Ash Davida Jane, John Prins and Paula Morris to share personal, critical and reflective views of the journal, each taking quite different tacks.

"These three essays offer a richly textured set of insights that, like all good essays, holds a mirror up to us all. I only wish I had room to include a whole lot more," she says in the review.

Wootton says Landfall Tauraka’s subscribers number "in the hundreds" and she would love to bump that up into the thousands to ensure its survival. Each issue costs $35.

At the launch of issue 250, she thanked Creative New Zealand for its support in recent years.

"Subscribing is the best thing you can do to help us keep Landfall Tauraka alive and kicking, doing what Brasch believed art does so irreplaceably well — expose ourselves to ourselves, explain ourselves to ourselves, see ourselves in a perspective of time and place," she said then.

The physical journal is "something special", she says.

"It comes back to the idea of having something there for half a year in your reading space that you’ve got to pick up, read through, get familiar with it. The importance of it for New Zealand and New Zealand writers is hard to quantify."

Statement of intent

Founding editor Charles Brasch knew what he wanted Landfall to be and to achieve. In his editorial "Notes" section in the March 1947 (Volume 1, No. 1) edition, he laid before the readers his vision for the new quarterly:

"Landfall is a literary review. Its chief concern is with the arts, of which literature is one. But the arts do not exist in a void. They are products of the individual imagination and at the same time social phenomenon; raised above the heat and dust of everyday life, and yet closely implicated in it."

Later, Brasch says:

"It is true that New Zealand is a long way from Europe. But it is true also that the European tradition can take root here and grow, if we wish it to do so. To think of this country as a mere province, a poverty-stricken outpost where nothing original can be expected to arise, is false and stultifying and the best way of ensuring that in fact nothing will arise.

"It was in total isolation that the Maoris (sic) developed in the centuries before our coming that vigorous, highly wrought, expressive art which is likely to remain for a long time yet the chief distinction of these islands. What counts is not a country’s material resources, but the use to which they are put. And that is determined by the spiritual resources of its people."