Today we're much too grand. We build smart "beach houses'' and like as not, they sit on the site of some family's beloved but demolished crib.

"Crib'' gives the game away. It's a synonym for a child's cot, a small stable, or an animal's feed trough. So when the first Southern family built its crib, it wasn't thinking it may end up in House and Garden.

"Bach'', the favoured northern term, comes of course from "baching'' - the forget-washing-dishes lifestyle the sensible male embraces when left to himself.

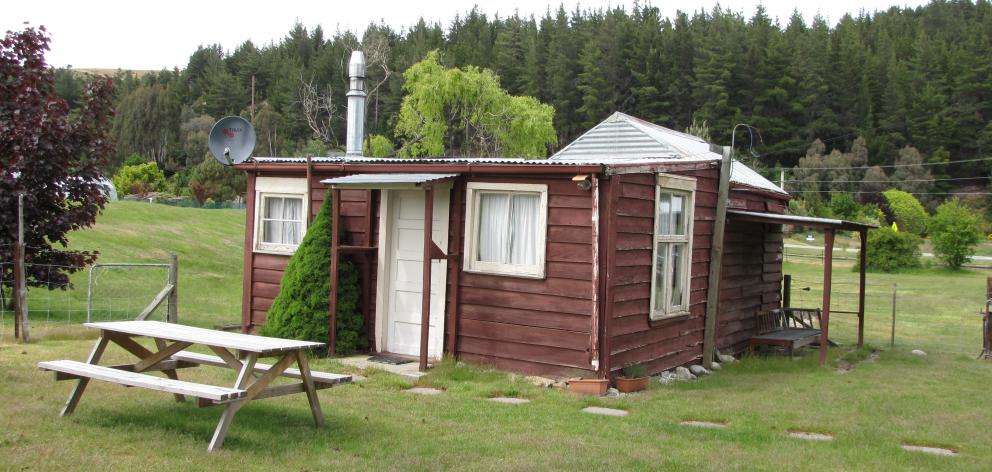

Cribs weren't raised from the minds of architects. Their design was the haphazard result of working bees by handy and unhandy uncles. Mates rate tradies did the tougher bits, and council building inspectors probably thought it convenient to consider the result none of their business.

A bloke was hired to drill a bog hole in a place nobody could agree on. And then, with the castle completed, the furnishings were scrounged.

We fantasise about these '50s and '60s baches and cribs as if they were part of an everyman's utopia. But the truth is they were typically the domains of the somewhat better off. The rest of us went to motor camps, where the smarter people had caravans, and the true plebs, tents.

But accidental social justice lurked in the background. Most motor camps were council-owned, so they were often perched on prime locations even the rich couldn't afford. I grew up in Waihi, by the Coromandel Peninsula, and for Christmas holidays we migrated 10km to Waihi Beach, where the family tent went up on a council camping ground that was so beachy it sat beside the surf club. This was summer bliss.

Then the family moved north to Dargaville, a town which, while it was going to the dogs, hadn't quite reached its destination. One of the country's pioneer bike gangs, The Stormtroopers, was launched in Dargaville, and its founders will have included old schoolmates who'd managed to lay their hands on coal scuttle helmets.

Fifteen minutes from the town's hub - the Northern Wairoa Hotel - lay one of the West Coast's wild black sand beaches. It stretched for many miles, the surf crashing in with the Tasman westerlies, the beach rich with driftwood, toheroa gatherers, and Morris Minors bogged to their axles. There were no palms or ukuleles.

This beach was reached down a narrow gorge that cut through steep sandhills - and here a bunch of early Dargavillains had bought waterfront land together, built baches on the shared block, and called it a "beach club''.

When one of the club's founding ancients passed on, the Lapsley family suddenly found itself in a position to join the local elite. We could buy in and become the owners of an absolute waterfrontage property.

The price was - wait for it - (Did I say Dargaville was remote and unfashionable? Did I mention the land wasn't freehold?) - Well, we paid fifty quid. One hundred bucks. Ten thousand cents for a place where you walked out your front door, down a kikuyu grass bank, and straight on to the sand. Even then, it was crazily, madly, cheap - less than a month's wages.

Unsurprisingly, the price came with the odd disadvantage. The interiors were the standard of a two-star chook house, and on any arrival, the first job was to sweep out the sand. There was no radio reception - forget TV - and no hot water. But for all that, the place had a rainwater tank, a long drop that fell to China, and it didn't leak that much.

While smartness was nowhere in its bones, a small do-up could have made this place reasonably liveable.

Then fortune chopped us off at the knees. My mother died unexpectedly, the family had to move to Auckland, and for a time things fell apart. But five years later I took a bunch of mates back for a weekend party that was such a raging success my father confiscated the keys, and (by chance, I hope) he sold it soon after.

Today, I wonder how we'd fare if we could stick the family's "absolute beachfront'' bach on Airbnb. Well, actually, I know how we'd fare. If a customer like me turned up, I'd take one look, gag, and demand my money back.

Sure, we've enjoyed our golden pasts. The mad thing is we couldn't hack them now.

John Lapsley is an Arrowtown writer.