Yesterday (May 31, 2019) was the bicentenary of the birth of the American poet Walt Whitman (1819-1892), and Dunedin has good reason to celebrate. Why? Because the Dunedin City Library holds the greatest Whitman archive in Australasia. Its current exhibition, "The Good Gray Poet'', shows off a selection of rare and beautiful works from the collection.

Walt Whitman was born in Long Island, New York, and he spent much of his youth there and in Brooklyn. The United States of Whitman's birth was still a very young country: James Monroe became the fifth president in 1817. Its literature was also in its infancy. Washington Irving's now classic story, Rip Van Winkle, appeared in the year of Whitman's birth. James Fenimore Cooper's historical novels of the American prairie, most famously The Last of the Mohicans, would appear in the 1820s.

As a young man, Whitman worked as a teacher and a newspaper writer. In 1842, he produced a novel with the uninspiring title of Franklin Evans, or The Inebriate: A Tale of the Times. In later days he did his best to ignore this early publication.

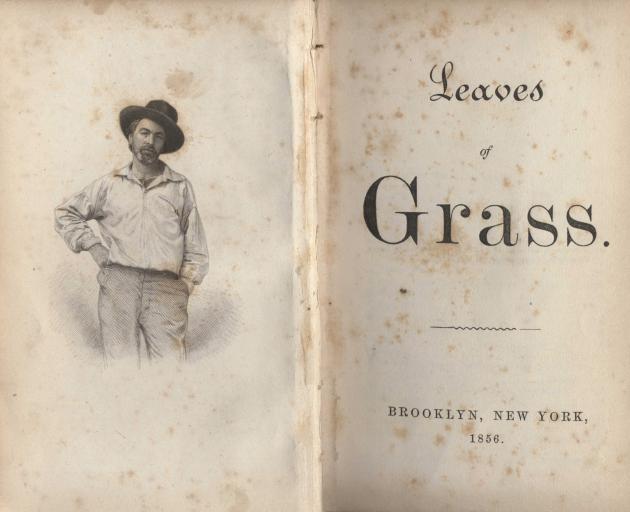

But the reason scholars and poetry lovers are celebrating Whitman's bicentenary is a volume of poetry that first appeared in 1855: Leaves of Grass.

Emerson was less pleased when Whitman published the letter in the second edition of Leaves of Grass. The spine of that second edition is gold-stamped with another line from the letter: "I Greet You at the / Beginning of A / Great Career / R.W. Emerson.'' Along with transforming English-language poetry, Whitman also transformed advertising. In one of his most famous poems, Whitman proclaimed, "I celebrate myself,'' and he certainly did.

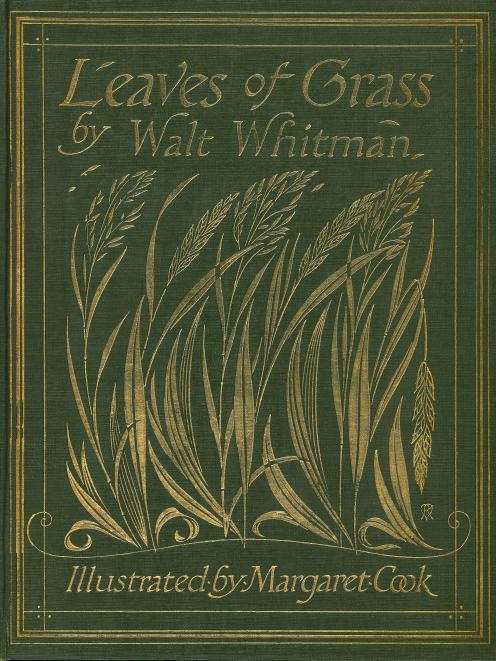

Whitman published other volumes throughout his lifetime, but Leaves of Grass is his key work. It continued to grow with each edition, often absorbing poems that Whitman had published elsewhere.

Why is it so important? One reason - evident even without reading a line of the poetry, but simply looking at its appearance on the page - is the fact that Whitman had embraced what we now call free verse: poetry that neither rhymes nor sustains a regular meter. Many scholars trace free verse in English at least to the King James Bible, especially the Psalms and the Song of Songs. Idiosyncratic poets before Whitman, such as William Blake, borrowed the rhythms of the King James Bible and of the inspired preacher for their own poetry. Whitman's British contemporary Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) produced his own experiment in free verse, the classic Dover Beach, a few years before Leaves of Grass, though it wasn't published until 1867.

But Whitman didn't just experiment with free verse; he whole-heartedly embraced it. In doing so, he made it the poetic voice of the US, and arguably the dominant form of all English-language poetry in the 20th and 21st centuries.

He also used it in a peculiar way. Whitman's poetry suggests an always-searching mind: observing, mulling over, repeating the same idea in different ways, as if looking for the right way to express something. Whitman's free verse links what John Keats called the "egotistical I'' of fellow poet William Wordsworth - that grand, poetic focus on the individual experience - with the narrative experiments of modernists such as T.S. Eliot who followed. Whitman's work was also ground-breaking and, to some, shocking in its overt, sensual celebration of sexuality and the human body.

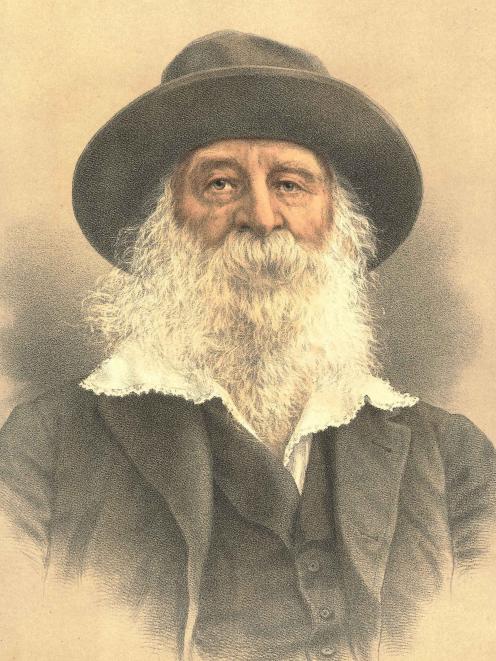

Whitman lost his government position in less than a year, perhaps because of his poetry's notoriety. In retaliation, O'Connor published The Good Gray Poet: A Vindication, in January 1866, and found Whitman another position. The pamphlet gave Whitman his nickname and increased his popularity.

Whitman also gained admirers in the United Kingdom. In 1868, a volume of his poems appeared in England, edited by William Michael Rossetti (brother of the artist Dante and poet Christina). In 1876, Bram Stoker - 20 years before penning Dracula - wrote to Whitman, telling him, "You know what hostile criticism your work sometimes evokes here, and I wage a perpetual war with many friends on your behalf.''

When he toured America in 1881 and 1882, Oscar Wilde regularly named Whitman as the American poet he most admired. Wilde wrote to Whitman in 1882, "There is no-one in this wide great world of America whom I love and honour so much.''

The innovative poet and Jesuit priest Gerard Manley Hopkins was more troubled by his intellectual relationship with Whitman. Also in 1882, he wrote a friend, "I always knew in my heart Walt Whitman's mind to be more like my own than any other man's living. As he is a very great scoundrel, this is not a pleasant confession.''

Whitman suffered a paralytic stoke in 1873. He left Washington for Camden, New Jersey (across the Delaware River from Philadelphia), to live with his brother George. He remained there for the rest of his life, entertaining visitors (including Wilde) and overseeing later editions of Leaves of Grass. He worked on the final edition of his lifetime, nicknamed the "Deathbed Edition'', in 1891. He wrote to a friend in December of that year, "L. of G. at last complete - after 33 y'rs of hackling at it, all times & moods of my life, fair weather & foul, all parts of the land, and peace & war, young & old.'' Walt Whitman died three months later, in March 1892.

His importance and influence would only increase in the 20th century. In 1917, Virginia Woolf wrote that the preface to Leaves of Grass "rivals anything we have done for a hundred years, and as a statement of the American spirit no finer banner was ever unfurled for the young of a great country to march under.'' Great American poets from Langston Hughes to Allen Ginsberg owe a debt to Whitman. Closer to home, a poet such as Sam Hunt seems unimaginable without Whitman's legacy.

Back at the beginning of the 20th century, Whitman caught the imagination of two serious New Zealand collectors: W.H. Trimble (1860-1927), who in 1910 was appointed the first Hocken Librarian, and his wife, Annie. Much of their collection was donated to the Dunedin City Library by their daughter, Dorothy Stewart, after Trimble's death in 1927. Today, the Walt Whitman Collection comprises more than 700 volumes, including rare editions of Leaves of Grass, beginning with the 1856 second edition (a facsimile of the first edition is also in the collection). This remarkable collection is currently being celebrated on the City Library's third floor. We owe a great debt to Rare Books Librarian Julian Smith and his colleagues for organising "The Good Gray Poet'' and for reminding us of the extraordinary gift given to Dunedin almost 100 years ago.

Tom McLean teaches English at the University of Otago. "The Good Gray Poet'' is on display in the Reed Gallery, Dunedin City Library, until July 7.

Comments

Walt Whitman is a problem for modern day audiences. If he were alive today he would be regarded as a notorious pedophile, due to his lifelong fascination and involvement with young boys, under the modern age of consent. In his own day, the age of consent was typically 10 years old, in most US states, and his "friends" were often not much older than that. Modern scholars typically airbrush that bit of history out, but anyone who does any research will draw that same conclusion.