There are choices to be made next month when the country goes to the polls. But first, the shopping, writes Leigh Paterson.

Some time ago, my friend and I were told we were more Countdown than New World.

The remark didn’t go down well; we knew what was being said. A class distinction was being made based on where we shopped for food. I had been scrutinised for many things previously, but supermarkets was a new one.

It has become a running joke between my friend and I, but the comment has stayed with me like a tattoo. This business of making sense of the world or creating your own brand identity based on what you buy, and where you buy it from, is part of Western consumerist culture.

Consumerism is a designed construct and one I’d like to investigate in this column.

With next month’s general election in mind, I would like to suggest that supermarket checkouts are perhaps more important than election booths. Consumerism is a form of voting. As designed entities, supermarkets are fascinating places we have constructed to help us hunt and gather, a primal pursuit. The act of shopping is a negotiation of choices and decisions: a transaction, which again is akin to voting.

In this survival of the fittest environment, that shares much with a casino (no windows, no clocks, bad music), a supermarket shopper is a gambler. Brands ask you to take risks. Through design, packaging promotes the best intentions of a product. But as a consumer how engaged are you in discovering what you need to know about the brand. Have you visited the factory floor? Do you know the conditions in which the product was made? How much are the workers paid? Where did the ingredients in that product come from? Do you believe in the company’s values and do you want to be aligned with them?

It is also important to acknowledge and reflect on whether you have the ability to make choices within that transaction. Many individuals would like to pay $8 for "ethical" cornflakes but are not in a position to do so. Regardless, you are absolutely taking risks every time you select a product and are passively engaged in a political transaction. It could even be said that you are endorsing the behaviour and practice of that company by giving them your money. This is a kind of "consumer election" that happens more frequently than general elections and is perhaps more influential in mandating change and reflecting what "business as normal" looks like. It is incredibly powerful.

Design in supermarkets allows everything to be "dressed up" in an artificial environment. Designers have a star role in these environments; telling consumers what they want to hear and solving all their survival problems. A shopper moves from brand to brand, positioning and aligning themselves in the consumption of the product. Design is on display and influences consumers as they buzz around in a dream-like state. And it is a type of dream state, because to try to get your head around all the brands and the noise that goes along with them is a full-time job.

The practice of design, to enable brands to promote and reflect the perception of choice and freedom by consumers within any market, is a false reality. However, a consumer experience while shopping can be incredibly powerful if the shopper can get under the skin of who owns the brand of choice.

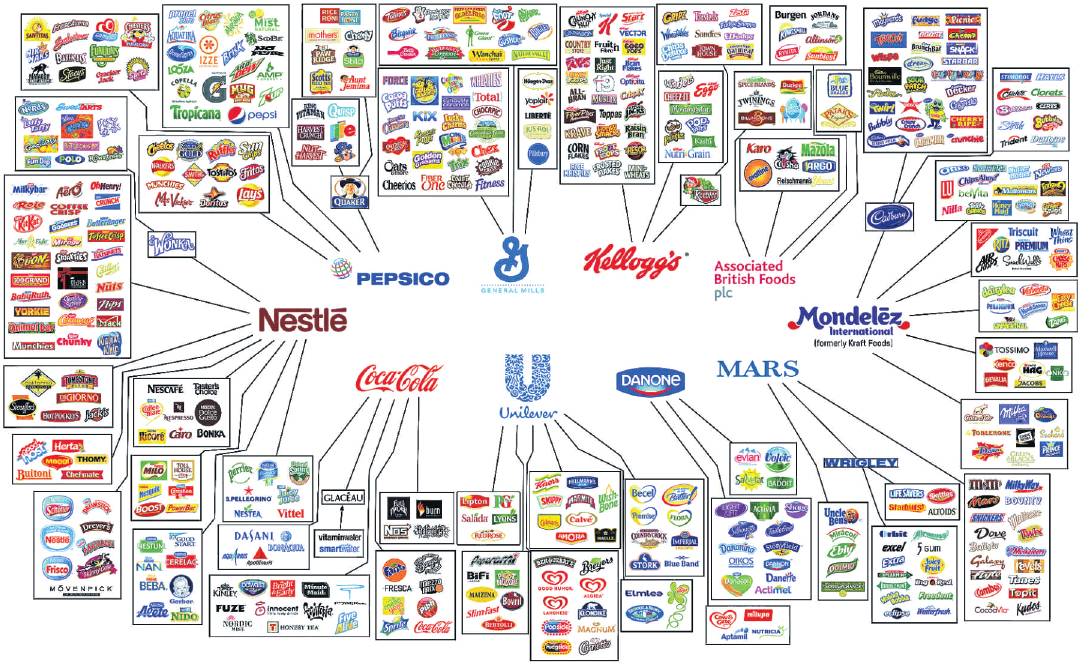

As an infographic from Oxfam shows, a complex web of conglomerate ownership ties one brand to another. For example, Mondelez owns Toblerone, Philadelphia spreads, Oreo biscuits and Freddo Frog chocolate: products that are marketed and positioned independently of each other, obscuring the common ownership. And in the example of Mondelez’ acquisition of Cadbury, it is apparent that this ownership model can destroy jobs and impact product ranges at the stroke of a pen. Pineapple lumps suddenly become a weird New Zealand lolly that won’t fit within a global market view. Does the whole world want to drink Coke and eat Mars bars? I’m not sure I would want to live in a monoculture where food is concerned.

Given the staggering vertical and horizontal integration of brands, that seem to move and change like a swarm, design becomes integral to creating and promoting difference. That’s why even though we think we know Nestlé as a brand we might not know they are in a joint venture with L’Oréal, which owns the Body Shop, Ralph Lauren and YSL. It’s like brands lead double lives in the way they operate in the marketplace and keeping up with all the "lived" parts of the brand is big business.

Take the Kraft Heinz merger in July, 2015. A quick online search reveals a complex picture. I was shocked to see how many brands Kraft Heinz owns in New Zealand, brands I had no idea had any link to Kraft Heinz. Not content with the spread of influence it currently has, there was a bid earlier this year by Kraft Heinz to acquire food manufacturer Unilever. That is a very powerful couple bringing another partner into the marriage.

UK Prime Minister Theresa May’s head was shaking as the Unilever takeover was being mooted due to the impact it might have on manufacturing and the job market. Governments are asked to step in from time to time to try to control companies’ power and influence in markets. But one begins to wonder if it’s the country or the company that is in control.

However, recent examples indicate that lobbying by citizens can have an impact. We have seen this in relation to investments by the NZ Super Fund and other KiwiSaver providers. Pressure has been brought to bear where fund managers are still investing in weapons, for example by not for profits such as Action Station. Perhaps in the future these investment funds will be strategic in creating corporate change. Perhaps we should be asking similar questions about what our money is supporting when we are at the supermarket.

Consumers also exercise power when they choose not to buy something, saying no to a particular brand. We are always making decisions, picking something off a shelf. In this respect maybe being a Countdown voter and/or a New World voter shows us much more about ourselves than food, highlighting what and who we buy into and why.

It is a manifestation of the idea that if you buy it, you believe in it.

- Leigh Paterson is a design lecturer at Otago Polytechnic.

Comments

We might also know Nestlé is Swiss, with a propensity to promote powder where there should be whole milk.

There are other issues than consumer choice. Supermarkets that detain elderly ladies with mistaken allegations of shoplifting are off the list.