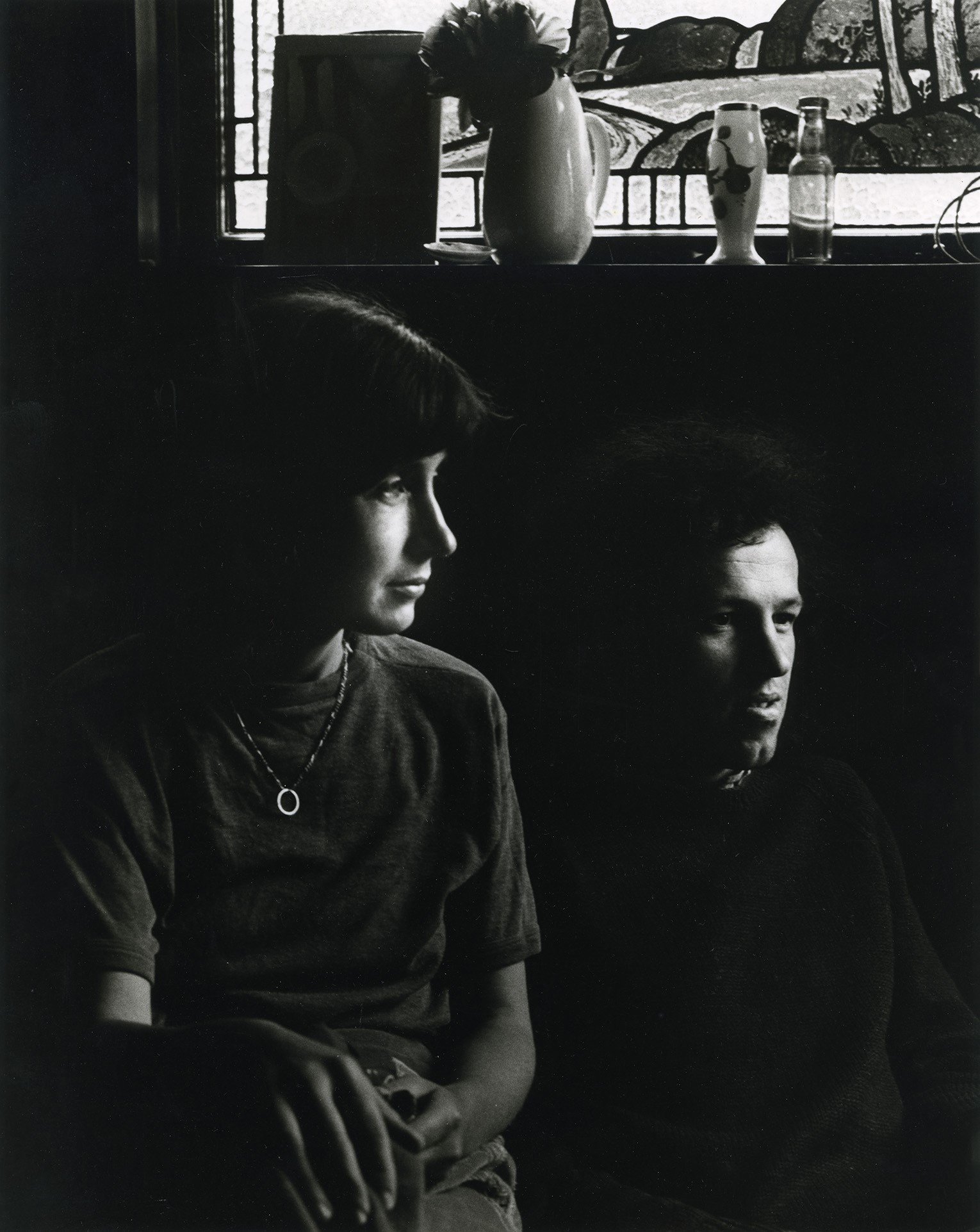

Jeffrey Harris was only 21 when he fell head over heels in love with Joanna Margaret Paul.

It was the first time he had ever been in love.

They met at a party at philanthropist Charles Brasch’s Dunedin home in 1970. Harris had recently been invited to Dunedin by mentor Michael Smither, while Paul, four years older than Harris, was living in Port Chalmers, part of a charmed circle of artists which included names like Ralph Hotere and Colin McCahon.

"I was knocked out by this intelligent person," Harris says.

"It was all based on art, the same sort of interests."

The couple were soon sharing a studio in Royal Tce and then married in 1971, moving to a small cottage at Seacliff, where they spent their time painting and drawing. It only cost $5 a week, and did not have hot water.

"It was quite primitive living, but we didn’t mind."

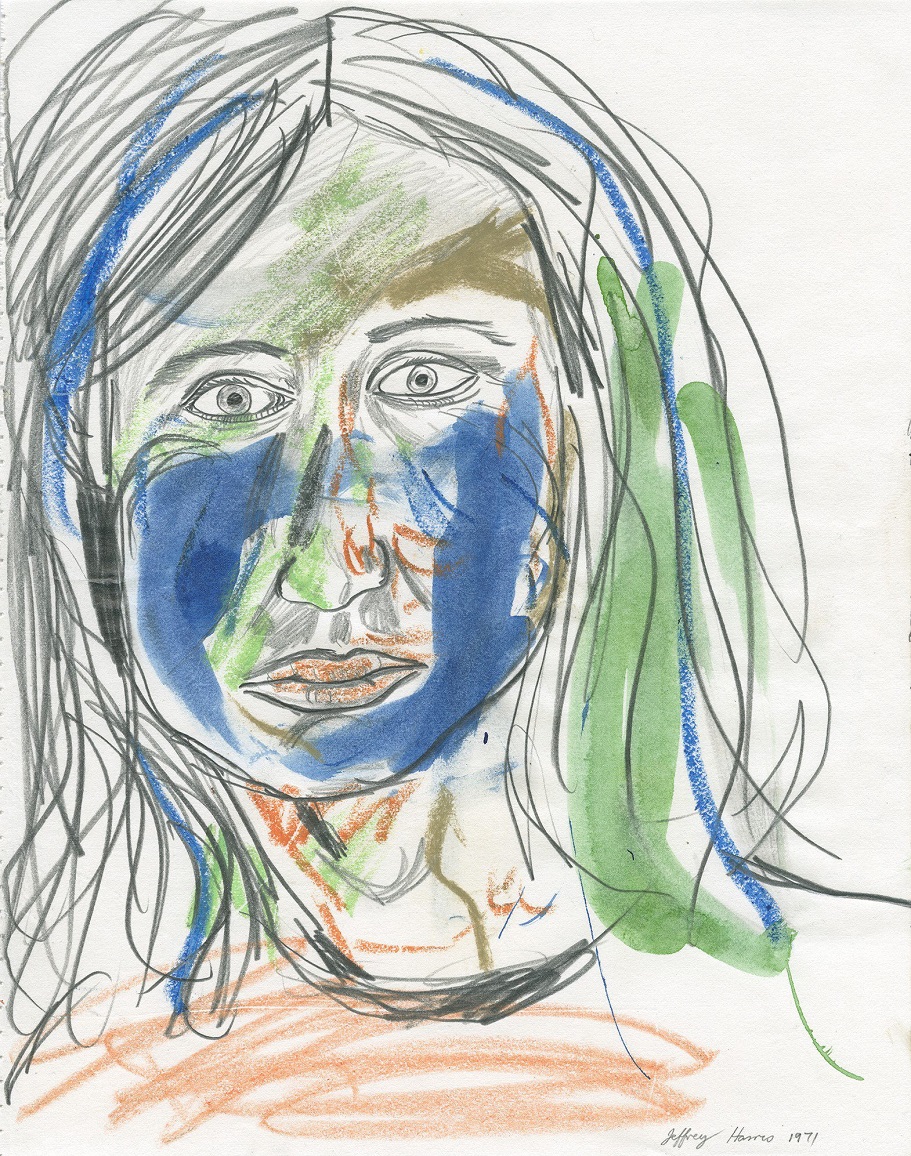

The besotted artist could not resist sketching his new wife, whether she was sleeping, reading, playing chess or just gazing out of window.

"It was a special time, sort of like a honeymoon period. It was good times, the best times. There was no pressure, in a sort of idyllic landscape, beautiful little house."

"I felt they should be seen. There’s quite a lot of work that has never been exhibited, it’s time to organise a lot of it — if I don’t do it, it won’t get done properly. It’s quite interesting from an historical perspective."

The drawings and paintings from life are the only ones Harris has ever done. He has never felt the need to do it again in other relationships.

"It was just that 12-month, year-and-a-half period that I did that. I don’t normally paint real people or from life or real drawings. It was a unique period.

"It was partly the influence of Joanna, she did a lot of paintings from life. When we met there was this cross-influence. I was influenced by her work, she was influenced by mine — but it didn’t last long."

The exhibition celebrates that period and hence its name, "Portrait of a Marriage".

"It was like a honeymoon period and once it’s over you can’t get it back. It’s a special time of life if you’re lucky enough to experience it."

When the couple moved to Wellington in 1973 life changed. Children came along, and so did the pressures of everyday life and a fulltime job.

"It was a whole different set of dynamics. That period of painting, that intimate relationship was over."

The couple, both of whom were awarded the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship — Harris in 1977 and Paul in 1983 — broke up in the 1980s.

He is not sure where that interest came from, as he did not come from a religious family.

"I self-educated myself with art books — I didn’t go to art school — I used to go to the Christchurch library and get out all these art books.

"A lot of the ones I was attracted to had religious imagery, they were of Old Masters and something connected there with me. So I started doing my own religious paintings.

"They’re nothing to do with religion, they’re to do with the intensity and emotions and feelings I saw in these paintings."

Later on he saw the religious paintings of McCahon and Smither, which were not an influence but more of a "connection", he says.

"I’ve always been drawn to religious imagery for some reason, I don’t know."

He first started painting in high school at the encouragement of a good art teacher, but studying art or a career in art was not an option, as his deeply conservative parents believed a job and earning money was the right move.

"My father was anti-university, he was a real conservative person. He took me to Christchurch one day and said ‘you’re going to get a job by the end of the day’."

About a year later he started painting again, and never stopped.

He contacted Smither, who encouraged him in his painting and helped him to start painting fulltime by providing him with studio space. Smither had moved to Central Otago in 1969 and came to Dunedin in 1970 for the Frances Hodgkins Fellowship.

"That’s when I came to Dunedin. He got me out of the job and away from my parents. I owe him quite a bit. My parents thought I was crazy, that I’d go back to the real world, but I never did."

Over the years, Harris’ work, mainly figurative painting, has gone through many changes and stages, such as when he moved to Melbourne in 1986, where his work became more abstract.

"It hasn’t progressed in a straight line, it has dipped down and gone around. I couldn’t do that work here, I don’t know why. It doesn’t fit in with my experience here. "

Much of his work is influenced by places, such as Banks Peninsula, where he grew up. In Melbourne the heat and landscape of the area were influences.

"Place is quite important, even if it is unconsciously."

Dunedin, where he has lived for more than 20 years, has always appealed because of its history and its "wintery cold" weather. When he returned to the city he got a studio in Bond St, not far from where his old studio in the Skinner Building was in the 1980s.

"It’s not too new, modern or plastic. I don’t like Auckland, I couldn’t work there. I can’t work with noise or distractions.

"The landscape is great. It’s my favourite place in New Zealand — the other place is Banks Peninsula."

"I’m looking backwards and going through things. It’s not really new work, it’s reflecting back. I’m revisiting a lot of those themes, a summing up of all the work I’ve done."

He admits to not being a "people person" and enjoying the solitary life of an artist, although that is not very good for relationships or having children.

"I’m addicted to it. I get very fidgety if I can’t paint or get to the studio, I get twitchy. I find it very calming painting. I’m at my happiest painting away and the phone doesn’t ring. It’s always been like that. It’s my life, painting, my driving force."

Until recently he had not really been aware of being part of a significant time in Dunedin’s art history back in the 1970s.

"People keep talking about it. I feel lucky in a way to have been part of it, as there were so many great people around at that time. It was good to have interacted with those people. It’s a bit thinner on the ground now. I think it was isolation then, you were in a pocket, you provided your own cultural stimulus. You were more supportive in a way of each other."

He hopes "Portrait of a Marriage" will be the first of many shows featuring his early work in themed groups. He has hundreds of works stacked up in his studio to sort through.

"Time is getting on with me. I walk past a lot of these works as I pass through the studio, they’re lying there. You think what’s going to happen to them. Getting older, you think about these things."

TO SEE

"Portrait of a Marriage", Brett McDowell Gallery, until April 18