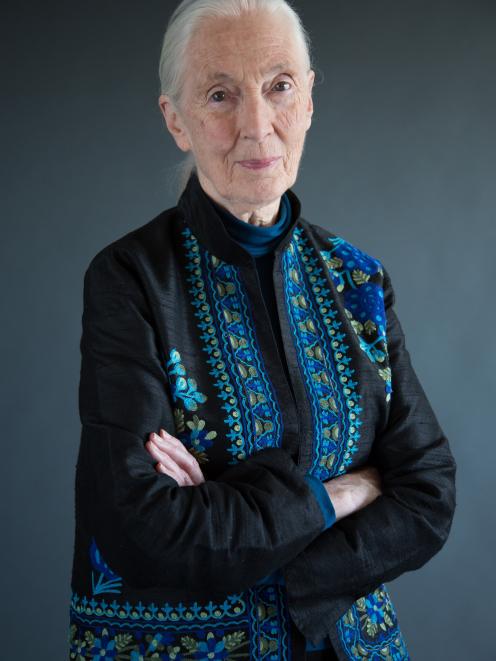

With regards to a photo shoot, she was completely and utterly opposed. This was problematic because the photographer had scouted an outdoor location the day before, coned it off, set up with a tripod and brought an assistant. This was Jane Goodall, the Mother Teresa of the animal kingdom. We weren't going to send someone in to just click.

But when the interview was over and she headed to the hotel lobby to meet the photographer, she said, "It's not a photo shoot is it?"

I hoped she was making a joke. As I now know, she wasn't making a joke.

"Oh I hate it," she said. "I hate it. I don't mind just `click', but the photo shoots, I hate them. I'd actually rather be in the dentist."

I laughed, nervously. "No," she said. "I'm really serious. I cannot bear a photo shoot. They're utterly stupid."

I said let's not call it a photo shoot. I told her not to worry, that whatever it was, it wouldn't take long. I assured her we wouldn't be going far. All those things would turn out to be lies.

We walked outside on to the leafy, meandering paths of the Bolton St Cemetery, and we took most of those paths. I assume we got lost. We walked for maybe 10 minutes, during which I became increasingly concerned about the wellbeing, both physical and emotional, of Jane Goodall, the global icon who changed the way we looked at animals and, by extension, ourselves, who is now 85, and whose time is incredibly constrained and valuable and used primarily for saving the planet, and who doesn't like photo shoots.

Who did I think I was looking at? This was Jane Goodall, a woman who had spent years living alone among the chimpanzees in the snake-and-leopard-infested stairless forests of north-western Tanzania. To her right was a narrow stand of small trees and bush atop a low wall. To my astonishment, she crouched down, pushed through the undergrowth and leaped off the wall, like some sort of youthful explorer whose knees had never once given her gyp; like an alpha primate.

She remained stoic throughout the photo shoot. By the time we finished, it was getting late and it was getting cold and after the ordeal of the shoot, I assumed she'd want to get straight back to the hotel.

Who did I think I was looking at? This was Jane Goodall, who brought up a child among the mortal threat of alpha predators while working full-time on world-historical research, then got a PhD from Oxford, then wrote a series of world-historical books then decided to devote the rest of her life to travelling the world spreading the good word. She asked to take the long way back.

Her message has always been one of hope but with the world now in a state of emergency, as climate change worsens and biodiversity collapses, hope seems such a quaint concept.

Nevertheless, she believes in it. There are good news stories, people doing good stuff, she says, and we must share those stories. She says she sees them all the time: "So many amazing projects, so many extraordinary people, who are really making major change."

We must not forget, she says, that in the wake of all the doom, there is hope.

"Without hope, people won't take action. What's needed now is action and rather fast ... Right now we are at a crossroads and that's to do with our survival."

She has taken action: she has set up 34 institutes around the world, which are named after her and designed to make the planet healthier and more sustainable. She's also set up a programme called Roots and Shoots, which basically has the same aim but for young people, in 60 countries. It's not conceivable she could have taken more action than she already has. She's not demanding we all take that level of action. In fact, we probably shouldn't.

She says, for example, we don't need more environmental organisations. What we need is for the organisations we have to work more effectively together. The competition between them, for resources, money, media space, is not helpful. She can see why it happens, she says, but she thinks it's sad.

"I'm hopeful but - and it's a big but - only if we get together in time and take action. If we don't, then there can't be any hope. So that's why I'm getting older but acting faster, because I don't have much time left and I'm obstinate and I'm not going to give in to the Trumps."

The documentary movie Jane, screening on Netflix, uses archival footage, presumed lost until a few years ago, to tell the story of her life among the chimps. It also shows the beginning, development and decay of her relationship with Hugo van Lawick, the man sent by National Geographic to photograph her and the chimps in the wild. She and Van Lawick would eventually be married, have a child and divorce.

The footage shows her washing her hair in a stream (footage National Geographic specifically requested from Van Lawick), poking her tongue out, looking thoughtful, climbing trees, playing with her son: "What a gorgeous baby," she says now. "I had forgotten how gorgeous he was."

Of the dozens of films that have been made about her since she first went to Gombe, she says, "that's the only one that took me right back there to my 26-year-old skin.

"There was a lot of stuff that was never used in film before, a lot of private bits, and it took me right back among those chimpanzees, who are almost like part of my family."

Van Lawick's photos and films of her are so iconic. I asked if she thought the impact of her work on the world would have been the same had it not been for them.

She said, "Yes, I do."

When asked if she felt born to the life she has led, she said, "I think I must feel that now. I feel I have to think that."

By way of explanation, she told a story about meeting a man from Papua New Guinea who had been chosen as "a messenger" by his people, selected to go out into the world and talk about the perils of destroying the natural world.

The story went as follows: The man was sent to England, aged 15 or 16, to learn English and was told somebody from Oxford would meet him at Heathrow, but nobody turned up. Eventually, a homeless man approached him, took him under his wing, and helped him learn English.

Once he'd mastered the language, he said to the homeless man, "I suppose I had better go to Oxford" and the man said, "No, I don't think you need it. You know as much English as you can learn at Oxford."

Goodall said he now travels the world as a messenger for his people, talking about our connection with nature.

"A very strange story," Goodall said.

I thought so too. I wondered what it meant.

She said: "After about half an hour, he looked at me and he said, `You do realise you're a messenger too."'

She said: "It was a very strange feeling."

She didn't go to Gombe to change the world. She didn't even want to be a scientist. She got her PhD from Oxford only because her mentor, the famed palaeoanthropologist Louis Leakey, insisted on it, so her work couldn't be easily dismissed by scientists. She had wanted to be a naturalist. Her dream had been to go to Africa to see wild animals and write books about them.

"You're a romantic," I said.

"Yes."

"Because science seems to clash with that idea, doesn't it?"

"Well, it's changing, and I've found some of the most thinking scientists, like physicists and so on, I don't know what percent, but many of them who have won Nobel Prizes, they believe there is intelligence behind the universe."

"Are we talking about God?" I asked.

"Some people call that God. To me, it's a great spiritual power and I don't know another name than God, so ..."

I asked if she could say more about that.

"It's just a feeling of a spiritual power which has given life to all the different creatures, and a better understanding of the interrelationship of all life. And I came to feel that - because we have language - we always want to ask these questions. So it seems to me that with this great spiritual power there was a piece of it inside us, linking us to the natural world.

"We have language, we want to name things, so we call it a soul. So, if we have souls, then animals have souls too. It's that simple."

I tried to compare and contrast the behaviour of chimps to that of, for example, Donald Trump.

She said, "It's very rude to the chimps if you try and compare any of them to Donald Trump. The point is Donald Trump is supposed to have a brain able to work things out. He should be able to control what he says - maybe not what he thinks, but he should be able to control his actions. Chimpanzees act the way they feel."

I asked if she'd ever met Trump. She said, "No. I don't want to meet him. It wouldn't help."

That morning, she had met Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, about whom she said: "If all politicians were like her the world would be a much better place."

She meets a lot of politicians, among an endless stream of other important people. As is well-known, she travels about 300 days a year and has done for decades, since first making the decision to leave Gombe.

"My schedule is a nightmare," she said.

I asked if she ever wished she could slow down.

"I wish I could just stop, but I can't."

I asked why she'd like to stop.

"Because travelling around getting through airports, never having time for myself, no time for writing, I can't have a dog, so it's horrible, but it's the only way I can spread a message. People say you can do it by video but it's not the same. I only say that because everybody tells me. People have said, `I've watched your films, I've read your books, I've seen you speaking on video conferences, but now I see you in person it's completely different.' So there you are."

I asked if this was something like the notion of spirituality she had been talking about earlier, of people feeling like they were in the presence of something.

She said, "Presence and connection."

I mentioned a story told to me by one of the organisers of her New Zealand visit, of two people breaking down in tears when meeting her at the $249 meet and greet session prior to her sold-out event at Wellington's Michael Fowler Centre the night before.

"Two?" she said. "There were about six. At least six. I know the two he meant though. The two were so emotional they had to leave and one of them didn't even come back."

"Is that a common experience for you?" I asked.

"Mmmm," she said.

"What does that feel like?"

"Well, it did feel very, very, very peculiar but I've gotten sort of used to it. I tell them: `Without tears in the eyes, there's no rainbow in the heart.' So then they cry more."

When the interview finished, we moved to the lobby of the hotel, which was quite busy. A good number of people turned and stared, without much shame.

By way of wrapping things up, she said, "So, anyway, the main message is that every individual makes a difference every day. We all have a role to play."

This is one of her most famous quotes. She must use it hundreds of times a year at her various speaking engagements. I asked if she ever tired of it.

"No," she said, "because they come up to me afterwards and say, `You've changed the way I think; I promise I'll do my bit."'

The perception of how much "my bit" is differs from person to person. With that, she headed out into the afternoon sun for what I think she already knew was actually going to be a photo shoot. - The New Zealand Herald