Pam Jones' grandfathers went to war. She remembers them.

Bert Jones and Murray Newman never knew the other existed as they lay in trenches on opposite sides of the world fighting Germans and Japanese among mud, rubble and tears.

But more than 25 years later the lives of two distant brothers in arms became forever entwined with the marriage of Bert's son and Murray's daughter, leading to shared grandchildren to ask innocent questions that brought proud soldiers out of their shells.

It was a childhood pastime that became a privilege.

Many men had breathed nothing of their wartime lives to their wives and children, but the passing of time saw many open up to new generations.

Curled up beside wise old men who had tried to get the best out of their lives, we knew we were hearing things that had remained untold for a full generation, and may never be repeated by them to anyone again.

Murray "Lofty" Newman gained new confidantes when his two daughters had their own children, but, like the "magnificent, aggressive, cool soldier" the unofficial history of the 20th Battalion of the 2nd NZEF says he always was, he kept careful control of which stories he told.

We weren't told of the journeys through hell we knew Murray had been part of - the battle of Cassino and time spent in Fabriano, Mignano, Sora.

"We ran into a bit of bother there," he would say thoughtfully when running into a battle in his stories. He would pause, then carry on with "when we finished, we stayed there for a while and then took off again."

Such was the way he skilfully avoided details he'd rather forget, instead dwelling on any good times he was able to have, because the lanky Middlemarch lad had left the family farm in 1942 determined to have an adventure, and so any time he wasn't fighting for his life he was determined to live it up.

Murray spent a year training in New Zealand and then based in Egypt with the 20th Battalion before he went to Italy, the source of most of his subsequent memories and stories.

Murray embraced the culture and was especially fond of Como, a lakeside settlement in northern Italy where he spent much of his leave time.

Stories of wine, women and song were later delicately retold within good-humoured earshot of Rena, the Bannockburn sweetheart he came back to marry, who good-naturedly kept up with his sense of mischief and adventure for 60 fun-filled years until she died in 2006.

Murray was largely deaf from being caught beside a tank that was bombed in a friendly-fire incident in Italy. By the time he reached old age he found following group conversation difficult, and you were better off sitting with him away from everybody else, where he could hear your questions.

It always seemed a good way to spend an afternoon, and as grandchildren we learnt about Murray's three months in a Senigallia hospital when he was shot in the kneecap; travels to Rome, Florence, Turin and Milan; and an unforgettable six months spent in Italy after the end of the war, when there was a shortage of ships back to New Zealand and Murray, by then a 2nd lieutenant, got to travel the country extensively while waiting to go back home.

We soaked up every story, knowing we would never have any real appreciation of what three years of wartime life and the return to a desolate Middlemarch had really been like.

But later, happily settled in North Otago and South Canterbury, Murray seemed to put a good spin on his experiences, and we were pleased he'd at least had some good times.

He considered his trip overseas as the wartime equivalent of our modern-day OE, and eagerly lapped up our own travelling stories later on, almost reliving his own time away with each adventure we told.

On the other side of the world, Bert Jones was fighting a very different war.

The Clyde rabbiter was part of the 29th battalion of the 2nd NZEF, fighting against the Japanese in the Pacific Islands as part of the third division, 8th brigade, D company.

It was an experience vastly different from that of soldiers in Europe, and when retelling his own stories, Murray Newman always expressed deep sympathy for the conditions those fighting in the Pacific Islands had to endure, in particular the fact that they never got to enjoy any respite with proper leave.

"I never saw a ship, a recreation ground or anything," Bert would later say. "We'd just go back to our tents at night."

Bert spent most of 1942 in basic training in New Zealand before being called up to go to New Caledonia, where they stayed for eight months, then going to Guadalcanal for several weeks.

As part of the 8th brigade, he then landed at Falamai, the Japanese headquarters on Mono Island, in the Solomons, on October 27, 1943.

It was the first opposed seaborne landing by New Zealand troops since Gallipoli, with the enemy pushed back after several days of fierce action, and communication lines established.

Trenches were dug and tents put up, with subsequent flare-ups serving to further test the nerves of men for whom the natural night-time noises of the jungle were ample reminder of the possibility of a hidden enemy.

Conditions were grim: Jungle warfare, incessant rain, fallen comrades buried in shallow graves on the beach.

Bert said they used old .303 rifles from World War 1, and their tents rotted in the jungle. There was hardly any food; at one stage the soldiers survived for three weeks on water and biscuits. First-aid supplies were scant, and outbreaks of dysentery were common.

Help came from American troops, who had a base at the end of Mono Island.

They supplied the Kiwis with food, stretchers, first-aid supplies, and even gave them American uniforms - the American shirt Bert wore home from war now hangs in my father's cupboard. When the New Zealanders left Mono Island, they went on American liberty ships, escorted by two destroyers.

My grandmother, Alma Jones (nee Odell), who died in 1991, explained patiently the absence of many wartime stories from her husband by saying some things were too painful to talk about, but she did tell us that Bert would never have a bad word said about Americans after he returned to New Zealand, as he considered them to have saved his life.

With few good things to say about the war, we knew Bert considered himself lucky to have served a relatively brief time in the Pacific before returning in 1944, but that his times of absolute blackness in the jungle had affected him forever.

Later a calm, unifying force on the family orchard in Roxburgh, he remained uneasy in the dark for the rest of his life. Offered a rise in the ranks to corporal at the end of his wartime posting, he politely turned it down.

Now medals, history books, photograph albums and our memories are all that remain of the war experiences of Bert Jones and Murray Newman.

Bert died in 2000 aged 93 and Murray in 2007 aged 88, both gentlemen and warriors who outlived their wives with trademark dignity, courage and fortitude, and continued to make a good fist of it until the end.

Neither of my grandfathers ever attended an Anzac parade, and neither had I until after Bert died, but, urged on by respectful great-grandchildren, I now occasionally stand at the back of one.

It's a solemn reminder of those who came before me. I stand and wonder: what will happen to the stories I and other grandchildren the world over have been told?

Like my grandfathers, I'll keep such confidences close to me and share the odd one, proud to be descended from men who were not just bastions of manhood, but, surely, of all humanity.

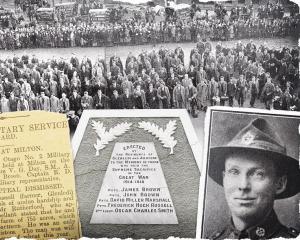

CAPTIONS:

Murray and Rena Newman, in the 1990s, at Timaru.

Mopping up at Falamai ... a photo from the book Stepping Stones to the Solomons: The Unofficial History of the 29th Battalion with the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force in the Pacific. The soldier turning to look at the soldiers lying on the beach at Falamai, on Mono Island, is believed to be Bert Jones. He remembers being on that precise spot when an Allied bulldozer (possibly American), buried a group of Japanese soldiers who were firing at Allied soldiers. Photo by the Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

Murray Newman (at front left) on leave in Italy, at the Colosseum, in Rome.

Murray Newman and Bert Jones.

Bert and Alma Jones on their orchard at Coal Creek, Roxburgh.