I say "celebrate" but it was more of an emotional journey, remotivating us all to keep doing our best to reduce single-use plastics.

From this dark point, the film-makers navigate greenwashing and recycling complexities to end on a message of hope, celebrating the companies in Aotearoa who have designed plastic out of their businesses.

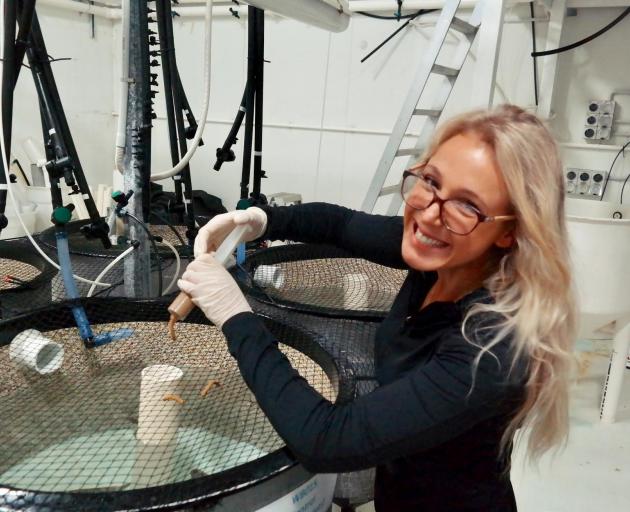

I was lucky to be joined for a panel discussion after the Wanaka screening by two inspiring women: For the Blue film-maker Adriana Bird and marine scientist and tertiary educator Veronica Rotman. Veronica’s research on microplastics in fish was so fascinating that I buttonholed her for a Q&A.

Q How did you end up researching the impact of microplastics on fish?

I was on a dive trip in the Philippines, where plastics inundate you from every angle. Coming across more plastic bags in the water than turtles makes you think about what the situation is back home. So when I came home to do my masters in 2019 with Niwa and the University of Auckland, I wanted to investigate the effect of plastics on fish species in Aotearoa.

Q Tell us a bit about your research?

Hoki is one of the most commercially valuable fish species, and I looked to see whether they were consuming microplastics in the wild. I dissected the guts of 60 hoki in total from three different locations (Cook Strait, Chatham Rise and the West Coast), and went through a series of chemical and mechanical steps to identify microplastics.

Q Was that a bit messy?

Yes, I was swimming in fish guts, and it took fricking ages so I spent a lot of time looking at fish guts, smelling like fish guts (on the train), and bubbling fish guts through various conical flasks and other sciency things.

Q What did you find?

I found on average between 4-7 items of microplastics in each fish, depending on location. The highest numbers were in the fish from the Cook Strait — probably due to proximity to human activity.

Just over 90% of the microplastics I found in their guts were microfibres (tiny plastic fibres from synthetic clothing, plastic rope, single use face masks and fishing nets). This is aligned with global scientific research about microplastics ingestion by fish and other marine critters — a review evaluated 46 pieces of research and found that microfibres were uniformly the prominent microplastic ingested by marine organisms.

Q How do plastic microfibres end up in the ocean?

A key source is through our washing machines’ effluent! Clothes can shed over 700,000 microfibres each washing cycle and effluent is processed through waste water treatments plants, which remove some microfibres, but not all. Even working at over 90% efficiency, there are still millions of microfibres entering the ocean each day from this source. Around 60% of our wardrobe is plastic textiles. We want to look spunky and buy some new clothes, but don’t quite realise these could be impacting our oceans, and kaimoana.

Q Do microplastics harm fish and other organisms?

The consumption of microplastics by fish has been shown to affect everything from their physiology to behaviour and reproduction. Multiple studies have indicated internal abrasions, blockages, toxicity, reproductive impact and neurobehavioural changes as just a few of the impacts.

The plastic itself is relatively benign, but it is the chemical additives that give it properties, such as colour, malleability, durability etc, and some are knowingly toxic to humans as endocrine disruptors — a fancy way of saying it disrupts the body’s hormone system causing developmental malformations, increased cancer risk, among other less than desirable effects. Plastics also act as a sponge to POPs (Persistent Organic Pollutants), these are industrial chemicals, pesticides etc that are already in the ocean and cling to plastic. Microfibres have a large surface area to volume ratio so they are much more effective at absorbing the pollutants.

Both chemical additives and POPs cause havoc in marine organisms, with varying levels of effects. Zooplankton that were exposed to microfibres produced half as many larvae, which were significantly smaller. As primary consumers of the ocean (consuming seaweed and algae, which are primary producers), they are a critical foundation of the ocean food chain.

Q Did you look specifically at the harm to fish from microplastics?

Yes, I also did a 10-week trial feeding "environmentally relevant" concentrations of microplastics to juvenile snapper in conjunction with their normal feed in tanks at Niwa’s Northland Marine Research Centre. I then looked to see how it affected their physiology. The average weight gain of the snapper was reduced in microplastic treatment fish, and some microplastics were shown to be able to stick around in the gastrointestinal tract for four days.

The retention time in the gastrointestinal tract basically determines the severity of the effect on the organism through the ability of chemicals to leach out into body and plastic to translocate through the intestinal system and into blood, other organs and tissue. Translocation or longer retention time means there is increased chance that the microplastics will transfer up the food web, when that fish is chomped by a predator species. Different microplastics stick around for different lengths of time, depending on the size, shape, chemical properties etc.

The plastic ingestion also changed the structure and architecture of the distal section of the intestine (that’s the back part of the intestine) which is super critical for absorbing nutrients and therefore enabling energy for growth. The microplastics compromised the permeability, efficiency and immunological response of the gastrointestinal tract. In the high treatment fish, we saw severe changes to the gastrointestinal tract structure.

We also saw evidence of small quantities of translocation of tiny particles of microplastics into fish muscle tissue. That’s relevant to us as humans, because the muscular tissue of fish is what we eat.

Q How did your research change the way you think about (and use) plastics?

It’s definitely a wake-up call with respect to synthetic fibres in clothing. It really made me think about the washing machine waste water — and I have done some initial work with a robotics engineer to try to create a wondom — a washing machine condom that would capture the plastic microfibres and prevent them reaching our oceans. There are already some filters available that you can put on or in your washing machine, and also "guppy friend bags" which help to reduce microfibre pollution.

It also makes you think about fast fashion — do I really need this item? I try to buy natural materials such as merino and linen, which have a significantly longer lifespan and won’t release plastic microfibres when you wash them.

Q What scientific research is in the pipeline to address the problem?

One really cool project funded through Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge is using matauranga Maori and marine science to explore using natural fibres to develop a sustainable and biodegradable mussel spat-catching rope. My professor, Dr Andrew Jeffs is spearheading this with Ngati Manuhiri and Ngati Rehua, and the project is being co-led by kairaranga (master weavers) of Ngati Manuhiri and Ngati Rehua who are matatau (expert) in the use of traditional plant fibre products.

The project has huge potential, because it is reducing the input of microfibres entering the marine environment, championing a natural resource and and celebrating matauranga Maori. It is a brilliant example of weaving indigenous knowledge in with Western science for better outcomes for the moana.

Q What is the most impactful thing individuals can do?

Think about how you can reduce the microfibres you put into our waterways. Buy less, buy natural fibres, wash your clothes less and use cold water washes. Also, reduce the amount of packaged foods you eat — chances are both your bodily temple and Mother Earth will be a little healthier.

Q What system change would you most like to see?

One easy win would be to adapt waste treatment plants and further filtration capacity to capture plastic microfibres before they reach the ocean.

I’d also like to see industry, government and consumers showing up to the party to make Aotearoa New Zealand a leader in this space. Plastic is not a bad thing, it’s just how we use it and our dependence on plastic in every facet of life.

Q Do you have hope for our oceans?

Absolutely, I wouldn’t do this job if I didn’t have hope. Plastic is an issue, but in terms of its effect on organisms and mass species, climate change is more complex and challenging. Plastic is easy to deal with comparatively — just stop making and buying it.

The film

Wastebusters screened For the Blue in Wanaka and Queenstown as part of the ResOURceful Communities project, funded by QLDC Waste Minimisation. If you would like to organise a screening of For the Blue in your community, email contact@projectblue.co.nz.