There is nothing scientific about grabbing two kerbside rubbish bags at random and sifting through the smelly mess to see what could have been diverted from the city’s almost-full landfill.

Nothing scientific, but instructive nonetheless.

Three bags are uplifted from outside three urban addresses. One holds only soiled nappies and is set aside for two equally weighted reasons: it skews the results and causes the gloved examiners to gag.

An hour and a-half is then spent sorting what was dumped in the remaining two rubbish bags — recyclable paper and card, non-recyclable paper and card, food waste, metal, recyclable plastic, non-recyclable plastic, sanitary waste and glass. The piles are then measured and weighed. It is revealing, not just of what lies beneath the bulldozed surfaces of our landfills and the waste practices that feed them, but also of Dunedin’s need for a new landfill.

At first glance, there appears to be no doubt the city needs a new spot to bury its solid waste.

The existing Green Island tip, opened in 1954 and capable of holding five million cubic metres of all manner of refuse, is filling up increasingly quickly.

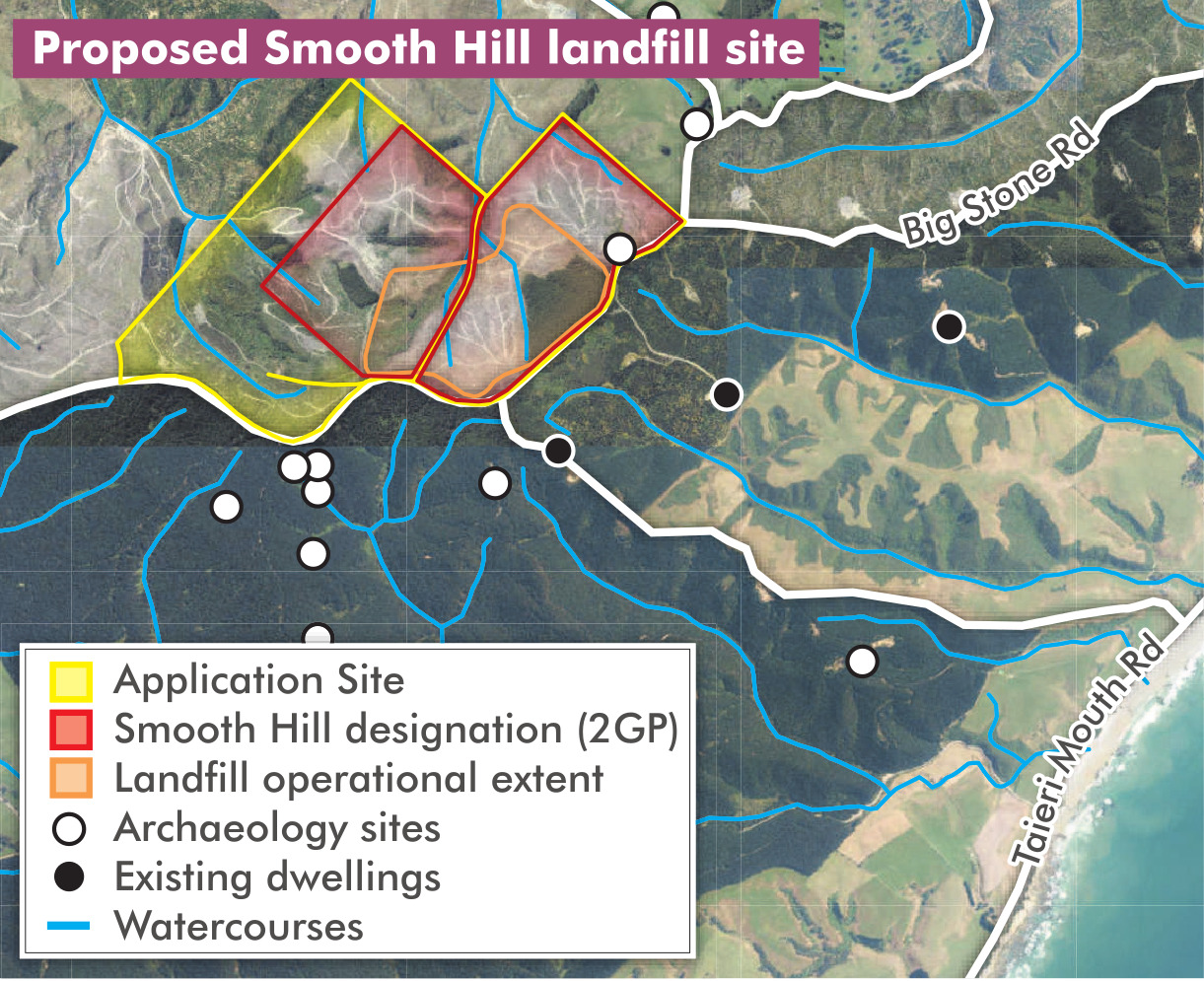

Council’s waste and environmental solutions staff hope that will be at Smooth Hill, a natural gully bounded by Big Stone Rd and McLaren Gully Rd, about 3km inland from the coast. A fortnight ago, the council lodged a resource consent application with the Otago Regional Council to construct and operate, at Smooth Hill, a six million cubic metre, 178ha, class 1 landfill with a life expectancy of 55 years.

The life expectancy is calculated on current Dunedin waste disposal rates — which at about 80,000 tonnes of trash per year, are another reason the argument for a new landfill appears self-evident. During the past two or three decades, New Zealand’s waste management practices have fallen behind many other developed countries, leaving us burying more, not less, used material in the ground, Duncan Wilson says.

New Zealand got its first national waste strategy in 2001, he says. But the ambitious plan was given no funding, nor any teeth, and not surprisingly achieved nothing. Then, in 2008, Helen Clark’s government enacted the Waste Minimisation Act, before promptly losing the general election.

The next government’s nine year "laissez faire" reign was characterised by a "do nothing and expect the market to sort everything out" approach to waste, Wilson says.

"During that time, New Zealand fell behind on a number of fronts, particularly with things like landfill levies, information gathering, product stewardship ...," he says.

Given such a sorry tale, Wilson says New Zealand is "doing better than it should be". While central government did not give a lead for two decades, local authorities, at the behest of their ratepayers, have been making some attempts to divert material from landfill, particularly through kerbside recycling schemes. A number of private groups have also taken steps to manage or reduce waste.

During the past couple of years, the Labour-Green coalition has been building capacity within the Ministry for the Environment to the point where, during the past six months, the Government has signalled a raft of waste reduction initiatives that could get the country back on par with other developed nations.

Right now, however, New Zealand is still sitting in the bottom half of the OECD league tables when it comes to good waste minimisation practices, Wilson says. We still produce a lot of waste (the most per capita by some calculations) and will be using landfills for some time to come.

If an almost-full existing landfill and New Zealand’s backwards approach to waste are two seemingly obvious reasons for a large, new landfill at Smooth Hill, there are a couple of equally compelling arguments against having any landfill at all.

Blumhardt is one half of The Rubbish Trip; a two-person, three-year, pan-New Zealand odyssey championing waste minimisation.

"Waste is a symptom of a broken system that doesn’t value resources," Blumhardt, now based in Wellington, says.

We live in a linear economy. We take, make and then waste resources.

But living on a finite globe, we cannot keep doing that and survive. At present, humanity vastly overshoots the planet’s ability to replenish the resources we consume each year. Estimates of that over-consumption vary from the equivalent of 1.75 earths to three earths per year.

Instead, Blumhardt says, we need to think in circles.

"We want to move away from a linear economy, where we use stuff and then chuck it in a hole in the ground, to a circular economy, where we keep things in use."

In 2017, an official audit of Dunedin’s rubbish bag contents found 11% of domestic rubbish could be recycled. The Weekend Mix’s random rubbish sampling suggests 15%.

Both of those figures only represent what is currently accepted for recycling. They do not take into account the non-recyclable plastic and non-recyclable paper and card resources we take, make and waste — 58%, by volume, of what was in those two rubbish bags.

Another argument for eliminating landfills is the environmental damage they can cause.

Fiona Clements says addressing that needs to begin with eliminating the word "landfill" so that we can see what we are doing to the earth and to ourselves.

"It’s actually Papatuanuku [Earth Mother] and that is what we should be referring to it as, because that is literally where it is going," Clements, founder of Res.Awesome resource recovery network, says.

The most significant, potential, harmful environmental products of landfills are leachate and greenhouse gases.

Leachate — rainwater filtering through decomposing waste into the surrounding environment — can contaminate waterways and aquifers and kill animals.

The possibility of leachate in Otokia Creek, which has its source on Smooth Hill, has been cited by opponents of the proposed landfill.

On that point, Wilson says landfill technology and design has come a long way during the past 20 years. A class 1 landfill would probably be built with a plastic lining on a clay base and would include a leachate collection system.

In theory it would prevent contamination, but in practice that would be hard to guarantee, particularly beyond the half century life of the landfill, he says.

The other nasty is greenhouse gases. Organic material such as lawn and hedge clippings and food waste break down in landfill anaerobically, without oxygen. This produces methane, a greenhouse gas that absorbs the sun’s rays to heat the planet.

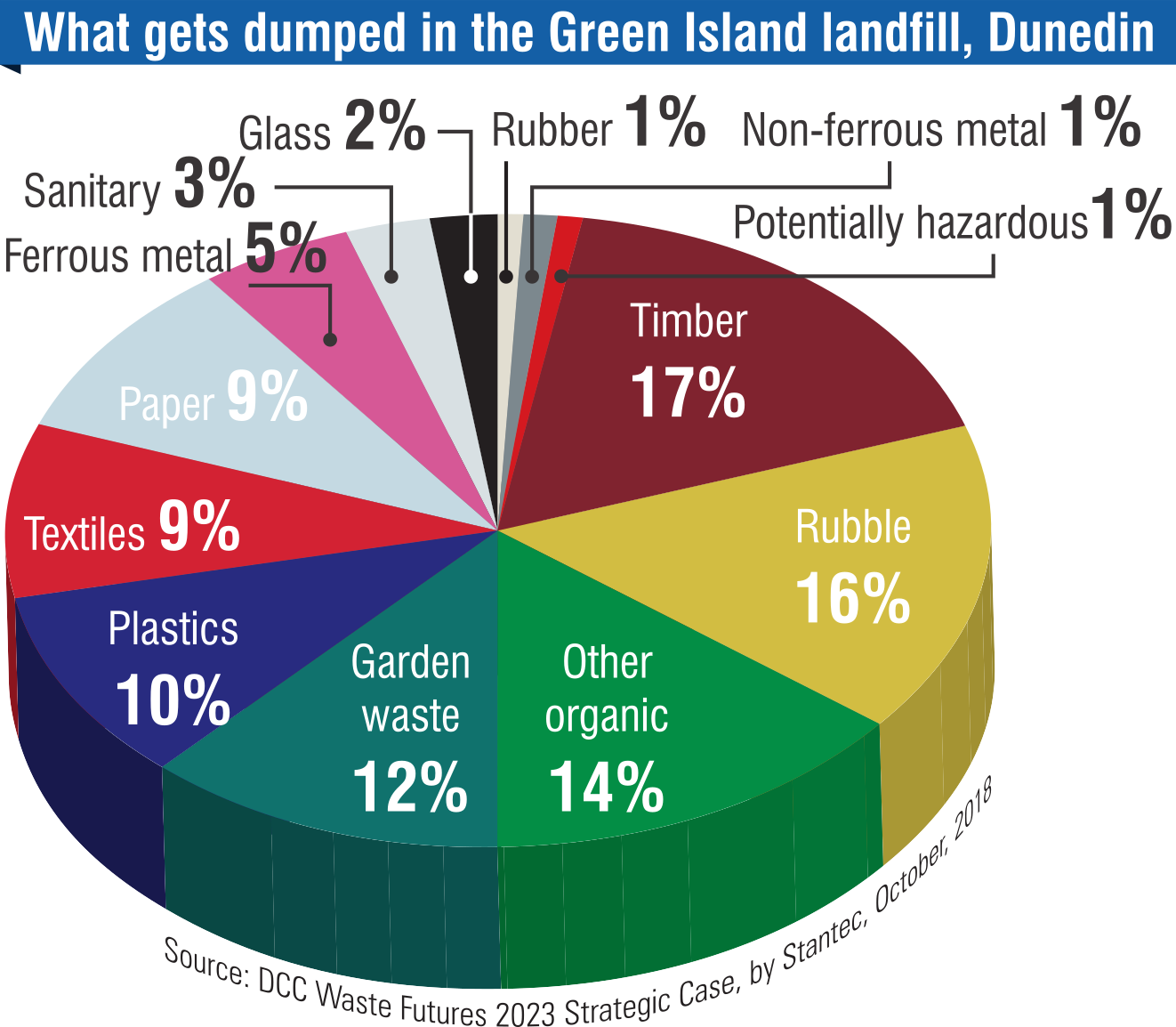

The council estimates those putrescible materials make up 26% of what goes to landfill. The Mix’s domestic rubbish bag sample included 18% food waste by volume, and 50% by weight.

Landfill gas is estimated to contribute 5% of New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Does Dunedin need a new landfill? The amount of waste we produce says "yes", the planetary degradation says "no". What alternatives are there? The obvious first step is to divert most of what is currently going to landfill. A second possibility is sending what cannot be reused or recycled to already existing regional landfills in Southland or Canterbury. But it appears local and central government have left it too late for us to do either quickly enough. A large Dunedin landfill will likely be the result.

But not because there aren’t alternatives.

The population of Waikato surf town Raglan swells sixfold to about 40,000 each summer. Despite that challenge, year-round the community diverts almost 80% of its waste from landfill.

The community-based group is contracted by Waikato District Council to manage the township’s waste. It does that through kerbside recycling, including food waste which it composts; prepaid rubbish bags, made of its own recycled plastic; street bins; and, a resource recovery centre, which has a shop as well as wood and metal yards. The 20% of waste that cannot be reused or recycled goes to the Hampton Downs regional landfill, which takes waste from South Auckland, Waikato, Coromandel and Bay of Plenty.

"When we first began, zero waste was just a philosophical idea," Thorpe says.

"But now here we are sitting on almost 80% using very simple methods."

Other much bigger centres are also picking up on similar approaches, he says. Auckland, for example, after many years of frustration at not achieving waste reduction goals, is making good progress by setting up what will become a citywide network of community resource recovery centres.

Thorpe believes Raglan’s goal of dealing with its remaining 20% of waste will be given a big boost by future initiatives announced by the Government during the past six months. Initiatives such as increasing landfill levies to better reflect actual cost; collecting more comprehensive waste data; recommending standardising kerbside recycling throughout the country, including separate food waste collection; a container deposit-refund scheme; and classifying six products — plastic packaging, tyres, electronic waste, farm plastics, agri-chemicals and refrigerants — priority products for which manufacturers and retailers will have to develop stewardship programmes.

In Dunedin, in May, the council introduced an updated Waste Minimisation and Management Plan.

The targets — including reducing the amount of municipal solid waste going to landfill by 50% or more by 2030 — mean tens of thousands of tonnes of waste will still be going into the ground each year a decade from now.

It is also unclear whether the council will commit to best practice, such as adopting household food waste collection, or find ways to disincentivise itself from treating a new landfill as a money making venture, for example by establishing the landfill as a stand-alone operation that does not give the council a financial return or adopting accounting practices that devalue the landfill asset as it fills up.

"Further changes could follow when the DCC consults the public on its kerbside collection service next year, as part of its 10-year plan process," Gledhill says.

"If the council chooses to operate a new landfill, the future operating model for the landfill would be a decision for councillors."

The South Island equivalents of Waikato’s Hampton Downs regional landfill is AB Lime, near Winton, Southland, and Kate Valley, near Amberley, North Canterbury.

The idea that Dunedin, rather than build a new landfill, could transport its waste to an existing regional landfill did occur to Wilson when consulting on the council’s preliminarily waste business case, in 2018.

"I was advocating that would be worth looking at."

What killed the idea, he says, was the information that demolition to prepare for the new Dunedin hospital build would contain a lot of asbestos and asbestos-contaminated material, which would need to be disposed of in a high quality landfill.

"And if you’re building a reasonably high quality fill, then you might as well build one that you can manage locally."

But this week, The Weekend Mix was told 70% of the estimated 55,000 tonnes of demolition material from the former Cadbury and Wilsons buildings is being recycled and that about 20 tonnes of asbestos material is going to the commercial landfill at Burnside.

So, why is the council still planning a large, class 1 landfill for Smooth Hill? How much waste would need to be diverted from landfill to make using a regional landfill a better option? When does the council forecast its waste reduction plans would reach that target?

In response, the council is saying little.

A class 1 landfill offers the best control and ongoing management for hazardous wastes, Gledhill says.

"We are unable to comment on your other questions at this stage, except to say the DCC is preserving its position while proceeding with the Otago Regional Council resource consent process."

There is a final business case, but that will not be made public for several months.

Asked, given that, how the public can have confidence the council’s plan for a Smooth Hill landfill is the best option, Gledhill says, "The case for the development of Smooth Hill is detailed in the various supporting reports already made public by the Dunedin City Council".

Despite unanswered questions about the need for a class 1 landfill, Wilson is not surprised a new, large, Dunedin landfill is likely.

"From what I recall ... it was something that had been kicked down the road by successive councils as being in the too hard basket," he says.

Setting up new systems and changing behaviour to reduce waste takes time. As does budgeting for a new system such as using a regional landfill.

"In a way, they backed themselves into a corner by leaving it until the last minute."

At the completion of The Weekend Mix’s random sampling, the rubbish lying in thematic piles is an odiferous testament to what could have been and what could yet be.

Food waste — moulding cheese, a half eaten chicken carcass, vegetable peelings, yellowing heads of broccoli, perfectly good yams and carrots, burnt toast — is the weightiest pile. Non-recyclable plastic — mostly soft plastics that held bread, sausages, noodles, instant coffee — takes up the most room. In other piles sit recyclable plastics, metal, recyclable and non-recyclable paper and card, glass and sanitary waste.

If those who filled these bags had kept the recyclables separate, if people composted or the council collected food waste, if the Government’s container refund programme and its plastic packaging stewardship scheme were in place — less than a third of this costly mess would need a hole in the ground.

Comments

One day humans will recycle or repurpose what they create and or consume. In a perfect world there would be no waste food with everyone only cooking the exact portion they will consume.

Instead of a tip, we could built a waste to energy plant to incinerate all but the dirt, concrete and metals. If only we had a population about that of Aucklands we could justify a very small plant. But we don't.

Until we reach some form of utopia, councils here and around the world need to plan ahead and make some form of landfill site available. How big just depends upon how fast people learn to divert waste to genuinly reusable purposes. But in the near term, councils would be environmental vandals to not have some reasonably accessible place to get rid of rubbish.

And the real issue is not how to dispose of rubbish, it is how to reduce waste before it is created. We can't even re-use the current plastics and glass set aside for recycling. So lets put the pipe dreams away for a while. Develop a new tip place somewhere and lets all try and cut our waste a bit. Banning sales of bottled water would be a start. Apart from natural disasters, no one in NZ need buy their water in bottles.