In the latest sci-fi novel by Kim Stanley Robinson, the head of a new international agency, the Ministry for the Future, must convince the world to step back from the brink of climate chaos.

The novel is set in the very near future and hardly involves any fiction at all really, given the calamities now befalling various parts of the globe as a result of planetary heating; drought, fire and flood.

But things can still get worse.

And in KSR’s tale, the head of the ministry, one Mary Murphy, is busy trying to convince the world’s central banks to only issue currency if it is backed by carbon reductions. Even capital must begin to care.

Meanwhile, back in New Zealand, the head of the newly minted Climate Change Commission, the closest thing we have to a Ministry for the Future, is saying all our spending and investment decisions should now be looked at through a climate change lens.

The man in that particular hot seat, in this our very real present, is Dr Rod Carr, a former banker and vice-chancellor of the University of Canterbury. He has admitted to being late to the issue of climate change, but in public pronouncements he appears to be making up for lost time.

"The clock is ticking, it is clear that action is going to be required," he said recently.

By Sunday, we’ll know more precisely what sort of action Dr Carr thinks is required.

Its advice, initially in draft form, is expected to land like something of a bombshell.

Adjectives attached to it, in anticipation, include "shocking" — that was Climate Change Minister James Shaw’s best guess — "challenging" and "confronting". Those latter two adjectives are from someone well placed to predict its tenor.

It will, at the very least, be sobering. New Zealand has become a climate action laggard. A recent OECD assessment put New Zealand second last, in terms of countries’ greenhouse gas mitigation efforts. Only Turkey was worse.

Here is Dr Carr again: "There’s no doubt that the transformation of our economy, from a carbon intensive high-emissions and utterly unsustainable technological and economic structure to a thriving climate resilient low-emissions future, will require costs to be incurred."

Precisely where the burden should fall is one of the areas on which the commission would like some feedback.

Once it releases its advice tomorrow, there will be a six-week consultation period, after which it’s final package of advice will be delivered to the Government.

For many climate watchers, it is the last throw of the dice.

As things stand, the planet is on track to heat up by more than 3degC this century, according to the United Nations Environment Programme’s latest “Emissions Gap Report”.

Under the Paris Agreement, New Zealand’s "nationally determined contribution"(NDC) to global climate action commits us to cutting our emissions by about 11% on 1990 levels. We’re not on track to achieve it.

Many countries have already made more ambitious pledges and at a United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow later this year, we will be expected to do the same.

Europe has now pledged to cut its carbon emissions by 55% from 1990 levels within a decade, up from 40%.

The latest headline recommendation from the UK’s Climate Change Committee is a 78% reduction in emissions between 1990 and 2035, fast-forwarding its previous plans by 15 years.

The pressure to meet such targets was ratcheted up another notch recently when new US President Joe Biden vowed to impose carbon fees on nations failing to do so.

Fair shares is most certainly part of the argument.

Dr Carr’s aware of that.

"I think fair share is a really good conversation for New Zealanders to have," he has said. "We’re a wealthy, developed nation. The wealthy nations, with the higher incomes per capita, do have a responsibility for doing more than the average."

And the average is already a demanding task.

Recent research calculated that the world’s remaining carbon budget, to keep warming to 1.5degC, is 440 billion tonnes. On that basis global greenhouse gas emissions need to decrease to net-zero by about 2040 — to give a 50% per cent chance of success. For a 67% chance, the researchers estimate, total CO2 emissions must not exceed 230 billion tonnes, which means net-zero emissions by 2030.

It’s the sort of science on which the commission will be basing its recommendations.

Climate scientist Dr Jim Salinger certainly expects so, which means more ambition and shorter timeframes.

"Our NDC, and it won’t take you to be Einstein to work this out, is not consistent with achieving 1.5degC. It is no way near that," he says from his home in Queenstown.

Dr Salinger, a co-chair of the organisation Wise Response, has long been a voice for climate action. He says the time is past when we could have taken a gradual approach to the problem.

"We have been dithering around since 1990, the luxury of just incrementally doing it is well and truly past.

"We are out of time, we have to do transformational stuff."

Auckland University of Technology climate change researcher David Hall will be looking to see where the commission starts drawing a steeper line on the emission reduction graph.

It could advise somewhat smaller cuts through to 2025, for example, while policies are put in place, then a steeper line through to 2030 and beyond.

Hall quotes the work of former Landcare Research scientist Robbie Andrew, who has estimated that every year the world fails to cut emissions uses up more than 10% of our remaining budget.

Andrew has estimated that we’re now looking at average reductions of CO2 of 18% a year, globally, and will probably need to actively remove CO2 from the atmosphere.

Massey University Distinguished Prof Robert McLachlan says the commission is likely to stiffen our Paris Agreement target and base its carbon budget recommendations around meeting that goal.

He suggests it might advise something like a 30% reduction in gross emissions by 2030 — short of what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says is required but doable. The current target is a 30% reduction in net emissions, a lesser challenge.

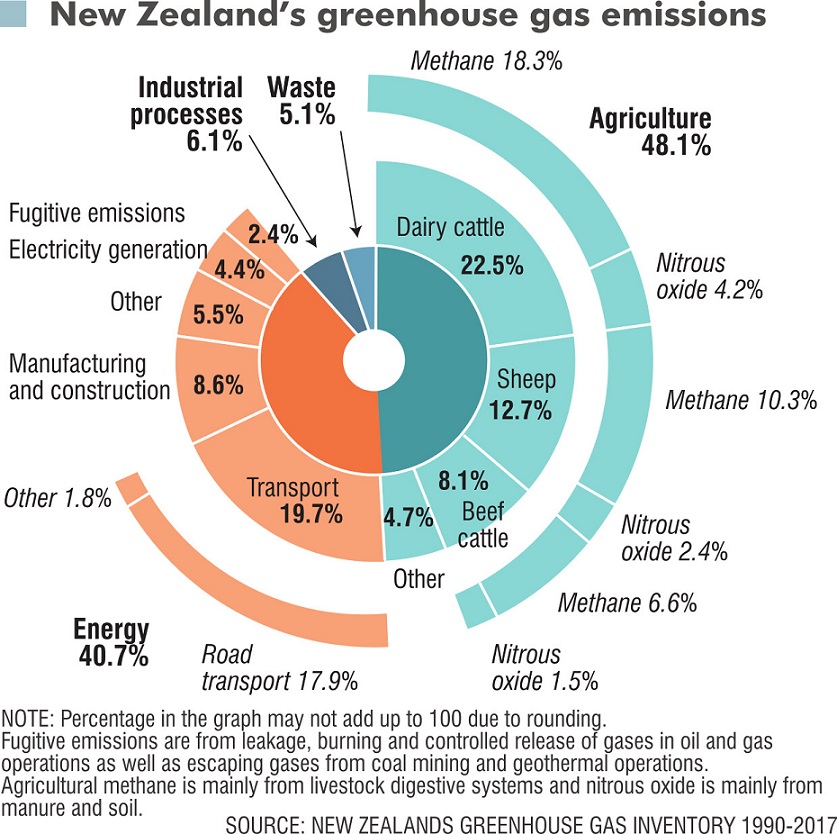

Salinger, Hall and McLachlan all say transport is likely to be a particular target for emission reductions, the focus on a rapid switch to electric.

Prof McLachlan adds that we can’t plant our way out of the problem with pine forests, we’re going to have to actually cut emissions.

Perhaps in anticipation of the commission’s advice, the Government this week announced several measures to reduce tailpipe emissions, including a "clean car import standard" phased in from next year and plans for zero-emission public buses from 2025.

There is a vast quantity of research on climate change now — what the problem is and what to do. Indeed, Dr Carr describes his journey of getting to grips with it all as drinking from a fire hose.

Among it is a report commissioned by the Ministry for the Environment and released in December last year, A safe operating space for New Zealand/Aotearoa.

"New Zealand exceeds its national share of the global climate boundary by over a factor of 5 for production-based emissions, and over a factor of 6.5 for consumption-based emissions," the report found.

The annual per capita CO2 emissions of the average New Zealander, of 7.3 tonnes, is many times the 1.85 tonnes the world can afford each of us.

At the 7.3 tonne rate we’ll blow through our fair share of the planet’s budget — to keep warming to the less ambitious goal of 2degC — by 2038.

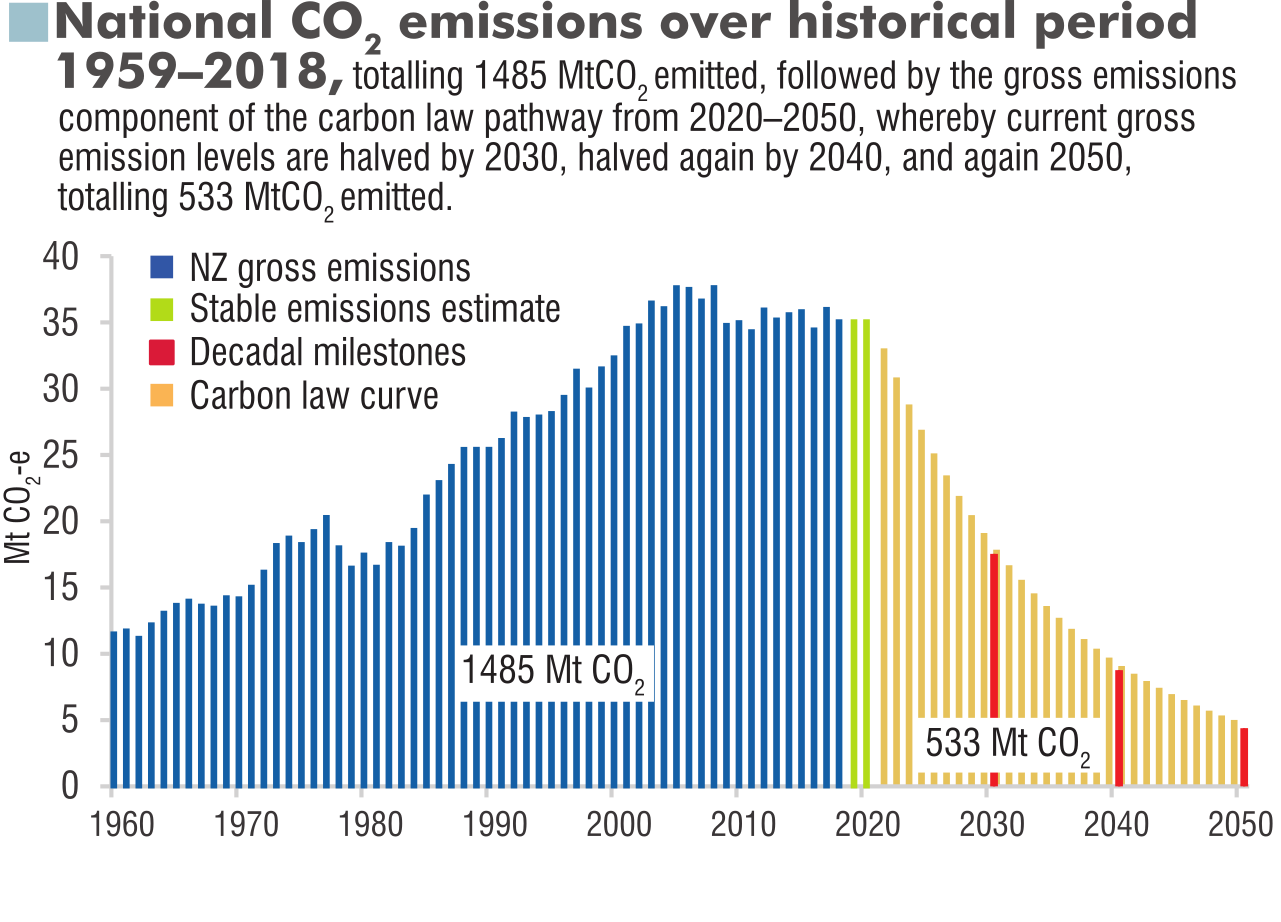

The report suggests cutting our emissions in half by 2030, in half again by 2040 and in half a third time by 2050 to hit a carbon-neutral goal.

That’s pretty consistent with commission member Prof James Renwick’s assessment.

The climate scientist says that if we are to keep warming to 1.5degC, the emissions we’d produce under business as usual through to about 2030, now has to be the total amount emitted through to 2050.

It will be tough, but he remains optimistic.

"I do feel hopeful for New Zealand," Prof Renwick said in a recent webinar. "We have a small economy, we can move quickly, we have lots of renewable resources. So I think New Zealand is well placed to be a leader globally in this area, and hopefully an inspiration and guide to other nations — ultimately a centre for technologies we need and the policies we’ll need to get to zero emissions."

In the near future of The Ministry for the Future, Mary Murphy assembles her team and asks to hear their solutions. Carbon negative agriculture, they say, clean energy, landscape restoration, the list goes on. Policies should include carbon pricing, industry efficiency standards, land use policies, industrial process emissions regulations, fuel economy standards and electrification, better public transport.

"In essence: laws."

Commission in the hot seat

The Climate Change Commission was set up under the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act, better known as the Zero Carbon Act.

It’s role is to "to provide independent, expert advice to the Government on mitigating climate change ... and adapting to the effects of climate change".

This it will do by recommending carbon budgets and suggesting how we meet them.

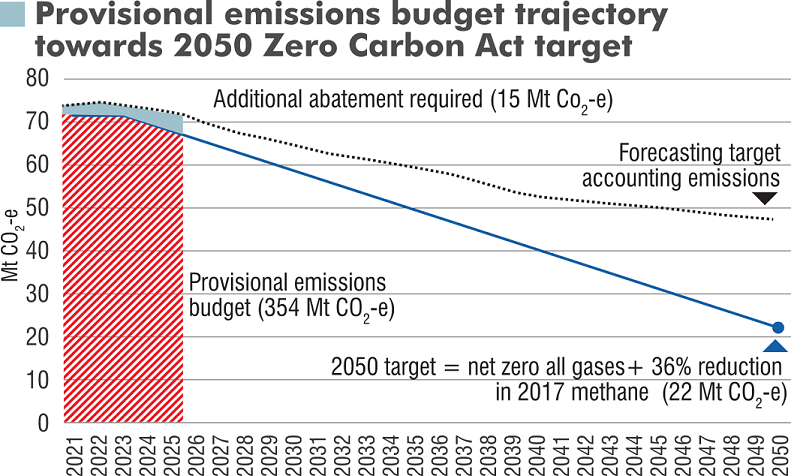

New Zealand has a provisional carbon budget through to 2025 of 354 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-e), set as part of reforming the Emissions Trading Scheme, which leaves room for only about 250 million tonnes for the second half of the decade if we are to meet our existing Paris Agreement target.

The commission will provide carbon budgets for three periods; through to 2025, the five years to 2030, and the following five years through to 2035.

It will also advise on how the emissions budgets "may realistically be met, including by pricing and policy methods".

It must also consider "the need for emissions budgets that are ambitious but likely to be technically and economically achievable".

While there is room for the commission to recommend the country meets some of its carbon budget commitments by buying international offsets, commission members have made it clear they do not favour this approach.

The advice

The Climate Change Commission’s first package of advice will include:

• The proposed first three five-year emissions budgets through to 2035 and guidance on the first emissions reduction plan, advising the Government on how the emissions budgets might be met.

• Whether our initial Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement is compatible with a fair contribution to the global effort to limit warming to as close to 1.5degC as possible.

• Advice on what reductions in biogenic methane might be needed in the future.

Submission period

• The commission will be consulting with the public from February 1 - March 14. An information meeting in Dunedin is being organised for Monday, February 15.

Feedback

Climate Change Commission chairman Dr Rod Carr says there are five big decisions to be made, on which the commission would like feedback:

• What should be the pace of change in reducing greenhouse gas emissions?

• How should the burden of transforming the economy away from fossil fuels be shared across society and over time?

• How much should wedepend on incentives and markets to do the job?

• What part should carbon removal (i.e., planting trees) play?

Ε How much should werely on domestic action and how much on international mitigation (buying carbon offsets) to meet our targets?