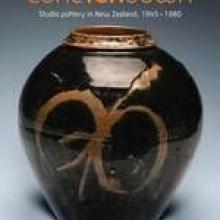

CONE TEN DOWN

Moyra Elliott and Damian Skinner

Bateman, $49.99, pbk

One of the most questionable legacies of the Lange/Douglas Labour government was the effect its policies had on the infant studio craft pottery industry.

I use the word "industry" intentionally, because by the early 1980s there were hundreds of craft potters making a modest but sufficient living all over the country.

They toiled away in their workshops trying to meet what became an almost insatiable demand for their work, so much so that some of the better outlets were ordering kiln-loads of pots before they had even been fired.

How this happy situation came about, and how it came to an abrupt halt, is the subject of Cone Ten Down, a book that should be on the shelves of every craft potter and pot buyer, for it is an excellent, thorough and generally level-headed account of a movement which has given much pleasure to many people, and impelled into being a permanent segment of our cultural identity.

While there had been successful craft potters in New Zealand before 1945, they were few in number.

The transformation of the state education system by Clarence Beeby and others, and the introduction of "art and craft" into both the school and the training college curriculums, were probably the two single most important local factors that led to the permanency of the craft potter.

And the visits in the 1960s by two outstanding studio potters, the Englishman Bernard Leach and the Japanese Shoji Hamada, defined both the early style of New Zealand craft pots and the methodology.

Some of our postwar potters studied with Leach and, to a lesser extent, Hamada, in their respective home studios, and on returning to New Zealand passed on their knowledge to local potters.

By this means, by membership of the many pottery groups, by apprenticeships, exhibitions and the like, skill levels were raised as was the crucial knowledge shared about glazes and kiln-firing methods.

At the end of the '60s, a core group of perhaps a dozen were producing quite consistently outstanding work.

Legions followed them.

Or they did until Roger Douglas removed the tariff barriers on imports which had sheltered locally produced pots from "market forces", and which suddenly saw a tidal wave of manufactured crockery flooding into the country from Asia.

Virtually overnight a successful local industry was brought to its knees.

So much for the vaunted "level playing field".

That is one reason why Cone Ten Down (a kiln-firing term) is concerned only with studio pottery from 1945-1980, the halcyon years.

No doubt someone will write a history as good as this of the subsequent years, for there is a grand story to tell about how studio pottery managed somehow to survive, to rebuild itself, and - while craft pottery is no longer routinely used in many households as much as it once was - has become an art form which, at its best, is of singular originality.

Cone Ten Down is beautifully illustrated by Haru Sameshima's photographs across a full range of the work of many of the best potters from the era; the influence of Leach and Hamada is carefully explained, as is the beginning of the necessary emergence from under their long Anglo-Oriental shadow.

Inevitably, there have been potters whom some readers will feel have been unfairly left out of consideration, but I think the balance is about right given the limitations the authors necessarily placed on their survey.

- Bryan James is the Books Editor.