After quarter of a century, industrial strikes are suddenly all the rage again. What forces have unleashed them? Should we be afraid or pleased? On the 67th anniversary of New Zealand's largest industrial dispute, Bruce Munro takes a look.

Kelly Gardiner stands resolute. She is, after all, a union delegate.

She grips one end of a colourful PSA union banner and steps forward, leading about 50 striking Inland Revenue marchers up a drizzly, lunchtime, Dunedin main street.

Behind the confident exterior, however, she is feeling a little anxious.

At 34 years old, this is the first time Gardiner has participated in a workplace strike.

The last time the New Zealand Public Service Association (PSA) union went on strike, she was at intermediate school.

A chant goes up from the striking placard-waving Inland Revenue workers who fill the broad footpath as they move north along George St.

''What do we want? Fair pay. When do we want it? Now.''

''Are we going to get public support?''

For almost a quarter of a century, New Zealand has seen little industrial action.

To a whole generation, workers walking off the job is a virtually unknown phenomenon.

But now, it is as though a switch has been thrown.

Late last week, hundreds of Farmers department store workers throughout the country left sale-hungry shoppers to fend for themselves for several hours.

On Monday, Gardiner, her Dunedin colleagues and more than 4000 other Inland Revenue and Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (Mbie) staff took a nationwide, two-hour work stoppage. PSA union members working for Inland Revenue have not been on strike for 22 years. If need be, there will be another strike in nine days, they say. Nurses had not gone on strike for three decades, until this week. At 7am on Thursday, up to 30,000 nurses and healthcare workers throughout the country went on a 24-hour strike after rejecting the District Health Boards' latest wage offer.

Asked why she was there, her 6-year-old Ernest replied, ''Because we want the nurses to be looked after and respected''.

At the time of writing, there was the prospect of more industrial action on the horizon.

The NZEI union says 47,000 principals, teachers and support staff will stop work for at least three hours in the middle of next month. It will be the first time teachers have taken industrial action since 1994.

Staff at five universities, including Otago, are also in pay and work-condition negotiations. Some say a strike on campuses the length of the country is looming. The list goes on. The reaction to this extraordinary flurry of strikes has been fast, furious and all over the shop.

Trade unionists and workers' rights groups have welcomed it as the much-needed reawakening of a long-cowed but now bellicose giant. Employers and business interests have taken full page advertisements in newspapers to lament what they forecast as a return to the bad old days of large-scale, 1970s, industrial strife.

In part, the work stoppages are simply because it's now cool to be radical, Dr Bryce Edwards says.

The political researcher and commentator says boring is out of style politically, and this is flowing through to how people think about their lives and industrial relations options.

''Strikes are definitely becoming fashionable again,'' Wellington-based Dr Edwards says.

''To some extent, this mirrors an increased radicalism happening around the world.''

Others have blamed the Labour-led coalition Government for raising workers' expectations and unleashing a torrent of industrial action.

Certainly, during September's general election, Labour worked hard to highlight workers' declining share of economic rewards.

''After nine years of National, working people's share of the economy is falling,'' stated Labour's election website.

Since then, Jacinda Ardern's Labour-led coalition has shown itself willing to address fair pay issues. Talking in January about proposed employment law changes that will swing the balance of power back towards trade unions, Workplace Relations Minister Iain Lees-Galloway said, ''Wages are too low for many families to afford the basics ... This legislation is the first step in the Government's commitment to creating a highly skilled and innovative economy that provides good jobs, decent work conditions and fair wages.''

But strikes would have been on the horizon even under a National government, Dr Edwards believes.

''Public sector wages have been static for a decade, and so there was always going to be a point at which public sector workers were going to take action,'' he says.

''It is likely that if National had been re-elected there would have been the same level of strike action this year.''

It is easy to be scared by the spectre of strikes.

The Business New Zealand chief executive says industrial action could escalate, given the Government's proposed employment law reforms. Industry-wide employment agreements, rolling back 90-day employment trial period provisions, union officials having unfettered access to work sites and forcing businesses to settle collective agreements all give him and other employers troubled dreams.

''There's a package of provisions that people might say is just a rebalancing,'' Auckland-based Hope says.

''Well, I think the consequences of a rebalancing are probably beyond what people want and they have a potential to increase strike action.''

Some stoppages might only affect strikers' employers. But those that affect logistics, such as getting food to supermarkets, or essential services, such as the estimated 3500 delayed elective surgeries due to Thursday's nurses strike, can cause significant disruption to the public, he says.

Do not overstate the case, Dr Edwards says.

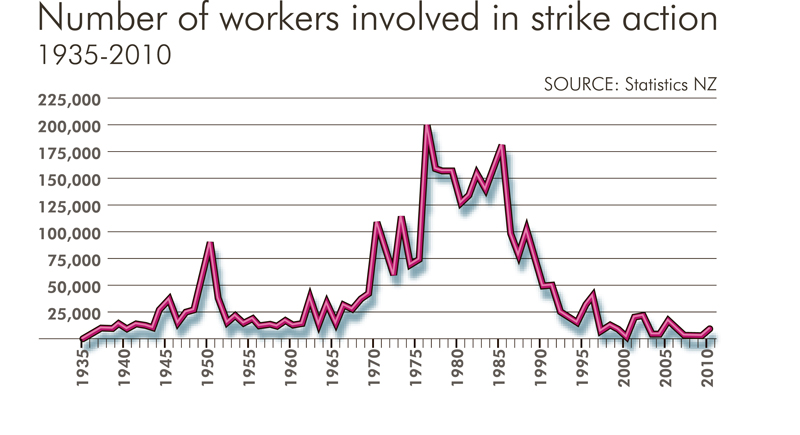

The number of strikes and work days lost has increased. But it is still a fraction of what it was in the 1970s and 1980s, he says.

''Also, it's important to realise that almost all these strikes are for very short periods, a few hours or a day,'' he says.

''This is quite different from the past, where industrial action could be much longer, or even indefinite.

''The current actions are often more about raising the profile of the issues and building public awareness than serious disruption to the employers.''

It was a brutal time, Malcolm says of the 1951 waterfront dispute that divided the nation and ended his dreams of becoming a lawyer.

Malcolm sen. was a watersider at Dunedin wharves when he and fellow members of the New Zealand Waterfront Workers Union refused to work overtime in protest over a low pay increase.

Their employers locked them out. Other unions supported the wharfies.

As the dispute gained momentum, the Government banned union meetings and publications. Gatherings of more than two watersiders could end in arrests.

It was illegal to give any support to the strikers, even down to giving food to their children.

''Telephone operators wouldn't put your calls through if you sounded like a wharfie,'' Malcolm recalls.

''It was hard going. There wasn't a lot to eat.

''But sometimes we received mystery parcels of food left at the back door.''

Malcolm, at 15, had to leave school and get work to support his family.

About 22,000 people were out of work for 151 days. That lockout, the largest and most widespread industrial dispute in New Zealand history, was the most recent of three waves of strikes, Prof Erik Olssen says.

Asked what strikes have ever achieved, the Dunedin-based emeritus professor of history replies ''an awful lot, over time''.

The French, Russian and Mexican revolutions all started with industrial action. But, unless it is a revolutionary crisis, strikes tend to be a mix of gains and losses, Prof Olssen says.

New Zealand's first wave of strikes was in the late 1880s. It ended with a maritime strike that was defeated. But it brought to power the Liberals, who laid the foundations for the later welfare state, set up an innovative system for settling industrial disputes that was embraced by employers and workers and gave women the right to vote.

The second wave peaked in 1913, on the eve of World War 1.

It was led by militant unions, the Red Fed - coal miners, gold miners, watersiders, seamen and some unskilled unions - who thought the arbitration courts were too slow.

Their demands were being met until they called a general strike, which they lost.

''They made some big gains, even while going down to defeat,'' Prof Olssen says.

The third wave of strikes built up to the 1951 waterfront dispute.The lockout started in the middle of February and came to an end on July 15, 67 years ago this weekend.

''That again culminates in a defeat. But once again, if you look at the fine print, many of the unions actually made significant gains; increased wages and better conditions.''

Malcolm's account bears some of the same ebb and flow of losses and gains.

The watersiders eventually accepted the original 9% pay rise offer, he says. The power of militant unionism was broken. Workers in other unions were given a 12% wage increase.

''What I learned,'' says Malcolm, who went on to become national president of the Maritime Union, ''was you had to be as good as the employers at negotiating.

''You had to fight for better conditions but also keep the men on the payroll.''

The efficacy of strikes past is also strongly suggested by mapping strike data on to labour's historic share of income.

In New Zealand, the number of workers involved in strike action peaked at 200,000 in the mid-1970s. It briefly rallied a decade later and then continued its steep downward descent. It has been bumping along the bottom of the graph, at between almost zero and 25,000 striking workers, for the past 20 years.

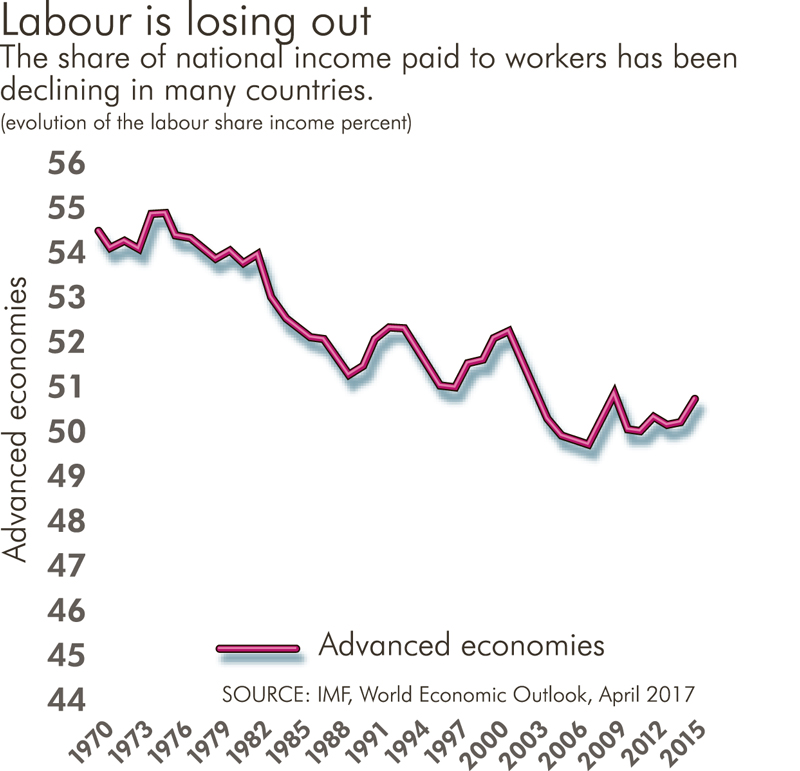

Last year, the International Monetary Fund, not known for socialist leanings, put out a worried report on labour's declining share of income.

''Labour's share of income declines when wages grow more slowly than productivity, or the amount of output per hour of work,'' the report's authors explained.

''The result is that a growing fraction of productivity gains has been going to capital.''

It is the same issue Labour highlighted during the election.

What the IMF's graph shows is that the share of profit going to workers has been dropping since the mid-1970s. Each brief, albeit reduced, rally in workers' share of income is also mirrored by a spike in strike action.

Prof Olssen also sees a similarity between the causes of each of the big waves of strikes and conditions today.

''There was often a broad perception among those joining unions that their wages were dragging behind inflation,'' he says.

''I think we can see parallels with now. The complaint from the teachers and the nurses is that we've had ongoing inflation of about 3% a year but they haven't had pay increases.''

This is why strikes are needed, Dr Brian Roper says.

''In order to put sufficient pressure on employers to grant substantial, reasonable wage increases, workers really do need to organise collectively and take strike action in pursuit of their demands,'' says the University of Otago political scientist.

Hope, Business NZ's chief, sees (almost) the same problem, but a different solution.

No, wages are not low. But, the problem is that the cost of living has been high, he says. So, yes, real wages have not been increasing much for most people.

But more union members on strike is not the answer, he says.

Access to cheaper overseas goods and upskilling workers is the Business NZ remedy.

''Our position is that gaining skills, not strike action, is the way to get better pay,'' he says.

It is surprising then, that the Economist - a free-market, global business mouthpiece read by those who own firms rather than those who work in them - says stronger trade unions are the way forward.

Last month, launching into the same dilemma exercising everyone these days - the stagnation of workers' real pay - it said a better understanding is needed of the relationship between pay, productivity and power. Wage bargaining is a negotiation to divide up the profit of a business between its owners and its workers.

''If firms have the upper hand ... employers capture most of the surplus,'' the magazine states.

It cites a recent study that estimates the rising power of firms has reduced labour's share of the profit pie by 20%.

A solution would be to increase workers' power, says the magazine in a glaring case of stating the obvious.

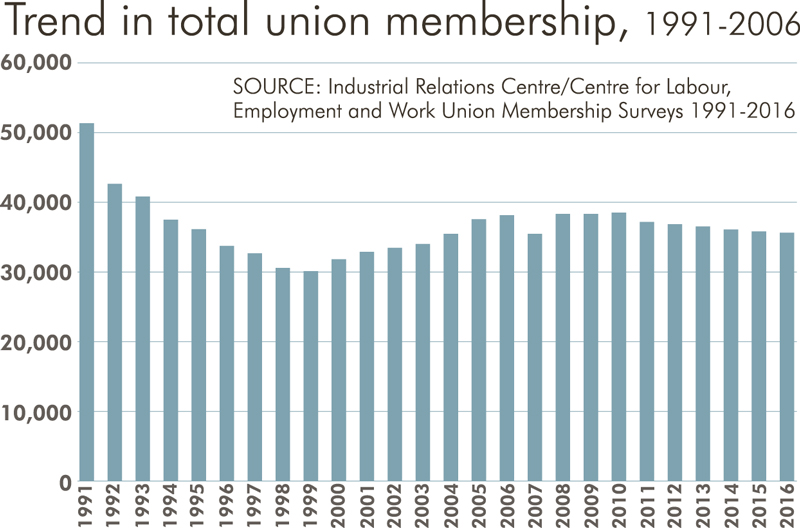

''Historically, this has been most effectively done by bringing more workers into unions.

''Across advanced economies, wage inequality tends to rise as the share of workers who are members of unions declines.''

To underline its surprising conclusion, the magazine points out that during the post-war decades, when unions were powerful, labour productivity grew quickly and real pay tracked productivity most closely.

''More empowered workers would no doubt unnerve bosses. But a world in which pay rises are unimaginable is far scarier,'' it warns.

When the lunchtime march reaches the intersection of George and London Sts, Gardiner turns left to lead the striking workers up the short, steep incline to the PSA offices and the promise of pizza.

She seems buoyed by the toots and claps they received during the stopwork march.''The public support was fantastic,'' she says.

''All we want is a fair pay system and a modest cost of living increase.

''This strike is a last resort, because bosses don't appear to be listening.''

Comments

Teachers and nurses pay is low, you say? They are employed almost exclusively by the government and have high rates of union membership.

So, if there wages are low this looks more like a government issue, and the union hasn’t been much help.

Now there is a Labour government they shouldn’t have to press too hard to have their demands met.

And the extra money to pay more will come from where?

Triage funding. We don't need an Americas' Cup, even less a Royal Tour.