In this edited extract from Vincent O’Malley’s new book, The Meeting Place, he discusses early interactions between Māori and European whalers in the South.

The shore-based whaling industry that began in south in the early nineteenth century was predicated on a high degree of active co-operation and agreement between local Māori and Europeans. Without that, no whaling station would survive for long.

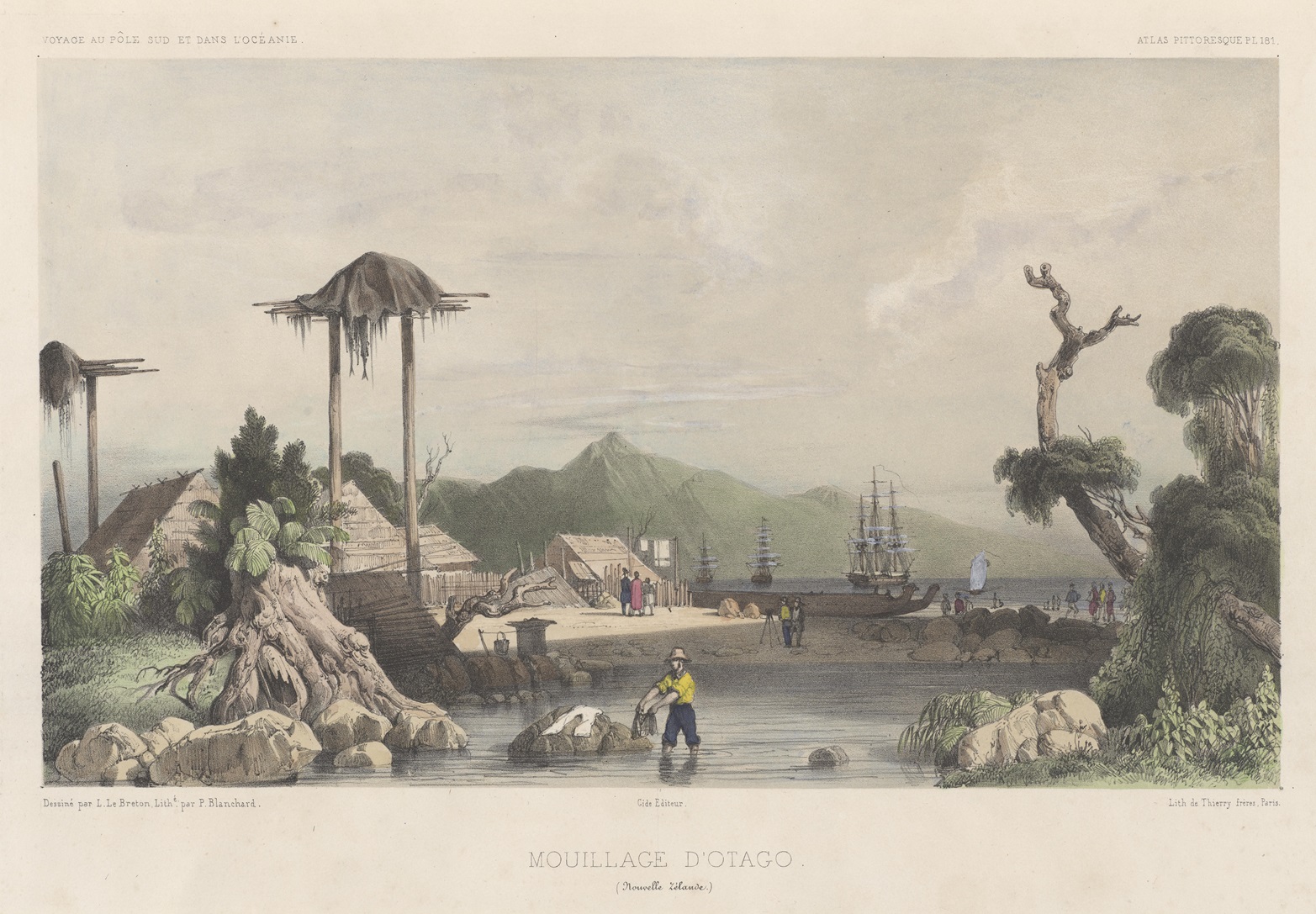

The first station was established at Preservation Inlet in 1829. Further stations sprang up at Otago after 1832, with others set up much further north, on Banks Peninsula, in the Tory Channel, at Port Underwood, Kapiti and the Māhia Peninsula. Again, Ngāi Tahu ownership rights were explicitly acknowledged through agreements in which the right to catch whales in specified areas were purchased from the tribe. At Ōtākou, the Weller brothers paid £100 for the exclusive right to catch whales between the Clutha River and Waikouaiti. In addition to the income received for whaling rights, Ngāi Tahu also wanted access to the firearms that trade and contact with the whalers could provide. The iwi was locked in a deadly series of conflicts with Ngāti Toa and their allies by the late 1820s, and desperate for muskets. They had also recently fought a devastating internecine conflict known as Kai Huānga (the eating of relatives). And significantly, it was the hapū in the Murihiku and Ōtākou areas of Ngāi Tahu who were instrumental in eventually driving Ngāti Toa from the tribal territory, thanks in large part to the muskets they had secured.

Shore-based whaling was a much more ambitious enterprise than sealing. For one thing, it required a substantially larger labour force. That meant a great many more Europeans in residence along the coastline (and on a more permanent basis than the small sealing gangs). It also provided significant opportunities for local Māori to earn an income through working directly for the whalers, or in providing them with pigs, potatoes or other foodstuffs. Edward Shortland estimated, for example, that between a third to one-half of the whalers employed at the Wellers’ Otago station were Māori, besides the many others hired for other land-based tasks. The presence of the whalers also opened up an export market for Ngāi Tahu, with dried fish, for example, being processed and sent to Sydney by the 1830s on board the whaling vessels. Regions with their own whaling stations saw an influx of Māori from outside the area in order to take advantage of these new opportunities. The advent of numerous single European men also saw an increase in the number of intermarriages. In fact, it was said that by 1844 some two-thirds of the young Māori women between Banks Peninsula and Riverton were living with Pākehā men, making it difficult for Māori males to find marriage partners. When it came to selecting marriage partners, not all of the European men were seen as equal. Key figures in charge of whaling operations tended to be paired with Ngāi Tahu women of rank, as was the case with Edward Weller. Along with his brother Joseph, he had been responsible for establishing a shore-based station at Ōtākou. Paparu, his first wife, was the daughter of local rangatira Tahutu, and Nikuru, his next, was the daughter of Taiaroa. Their daughter, Nani, would marry Raniera (Daniel) Ellison from Te Ātiawa, founding the prominent and influential Ellison whānau.

By the mid-1840s shored-based whaling in the south was already in decline, and many of the former whalers and their wives turned to fishing, farming or boatbuilding for a living. It was the children of these mixed marriages who learned to bridge the cultural divide of their heritages. Edward Shortland, travelling between Akaroa and Bluff over 1843–44, estimated there to be "little more than three hundred" such children in this area. Yet his casual dismissal of this figure as "very trifling", ignored the reality that such a number in all probability represented a significant proportion of total Māori children in the area. For although some observers hoped or believed that intermarriage would result in the eventual disappearance of Māori in southern New Zealand, the children of these unions overwhelmingly identified as Ngāi Tahu, helping to influence and shape future tribal identities.

Complicating the picture further, not all the men who fathered these children were white. Some were Indigenous Australians who had gained employment on board whalers or sealers that visited southern New Zealand. Tommy Chaseland from the Hawkesbury region was one example. He married Puna, the sister of Taiaroa and a woman of great mana in her own right. They lived at various places in the south and although the marriage produced no heirs, after Puna died Tommy married another Ngāi Tahu woman, Pakawhatu. The pair had two daughters and two sons and today have many descendants.

As the Anglican bishop, George Selwyn, observed during an 1844 visit to the south, most of the children from Māori marriages with whalers and sealers were bilingual and in effect sometimes acted as cultural intermediaries between their parents. Selwyn’s own measured assessment of the whalers, who in his view clearly loved their children and were able to "impart a considerable amount of civilization to the natives", stood in marked contrast to that of many other "respectable" visitors. George Clarke Jnr, for example, observed after visiting Otago that "[t]he natives appeared to be in a miserable condition. More than in any other part of the country they had suffered by their intercourse with the very roughest of whalers and sealers, and altogether they were in a more pitiable state than any of the tribes in the Northern Island". But missionary assessments of northern Māori encounters with the lowest orders of European society were hardly any more flattering. The great unwashed were not the preferred agents of acculturation (especially if they happened to be Irish Catholics, as was the case with many former convicts from the penal colonies who gained employment as whalers). Whalers themselves took a different view. Observing the relationship between the formidable Ruapuke chief Tūhawaiki (or "Bloody Jack" as he was sometimes known) and the European residents of the south, Edward Shortland observed: "We were much amused at the pride the whalers evidently took in him. He was both their patron and their protege; and was appealed to as evidence of what they had done towards civilizing the New Zealanders." When Tūhawaiki signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi at Ruapuke in June 1840 he came on board HMS

Herald "in the full dress staff uniform of a British aid-de-camp, with gold lace trousers, cocked hat and plume ... accompanied by a native orderly serjeant dressed in a corresponding costume". The rangatira spoke English, could read and write, and had become a highly accomplished businessman, even employing a European, Henry Hesketh, to act as his secretary or agent. Hōne Tīkao, also known as Johnny Love, who had signed Te Tiriti at Akaroa, was fluent in French after travelling to Europe on board a whaler.

While many men of the cloth feared that contact with the sealers and whalers had corrupted southern Māori, and others asserted its "civilising" influence, the phrase "patron and protege" suggested altogether less unidirectional influences at work than either side of that argument might have imagined. In this respect, although the specific patterns of encounter in the south differed in important ways from those further north, the underlying processes of navigating the middle ground shared some familiar features. And after 1840 early European migrants to southern New Zealand were at first entirely reliant upon Ngāi Tahu to feed them, to build their homes and to provide a range of other services. A mutually beneficial relationship survived for some time before eventually being swept away in a wave of mass land purchases, broken Crown promises and demographic inundation by the 1860s.

The book

• The Meeting Place: Māori and Pākehā Encounters, 1642–1840, published by Bridget Williams Books, is out now.