He stands, unassuming, near a corner of the Otago Museum board room this wintry Dunedin morning, while museum director Ian Griffin speaks.

Dr Griffin is singing the praises of one of the dozen people gathered around the board table spread for an evidently auspicious occasion.

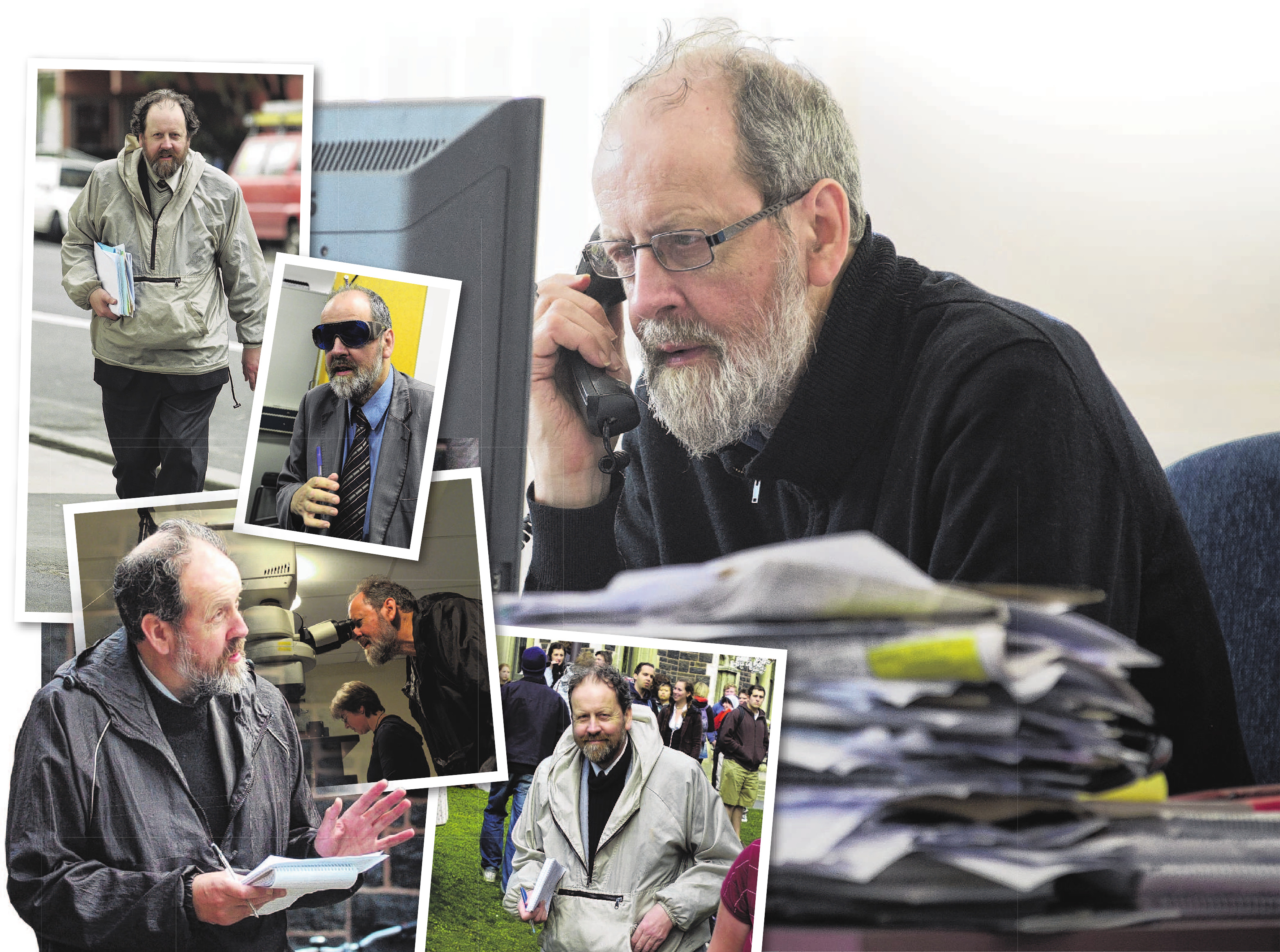

On any ordinary day during the past 33 years, the assumption would have been that Gibb was here to observe and report on whoever was receiving this glowing accolade. But his fingers do not grip a pen scribbling in a notebook - not today.

"You have done amazing things for this museum," Dr Griffin says.

"From my perspective your departure is very sad.

"You are a legend and lots of people in this city have a high regard for you, John."

Yesterday, Gibb logged off his computer at the northern end of the large, open-plan Otago Daily Times (ODT) newsroom for the final time. It was the conclusion to an almost four decade-long career as a journalist, most of which was spent with the ODT.

For years, his desk’s mountainous piles of paper (board agendas, council reports, story drafts, magazines, shorthand notepads), grudgingly making room for his computer, spoke to the thousands of stories he has written, the tens of thousands of people he has interviewed, the millions of words he has had published informing people of what is going on in their town and in their time. But yesterday, the paper stacks were gone. The time for asking questions had come to an end. It was time to answer a few instead.

"I do hate this," Gibb says, having already asked for the questions in advance.

"I’m used to asking questions. Being asked them, it’s almost incomprehensible."

It is an interview technique Gibb learnt early, the hard way. In 1984, while at journalism school, he did a phone interview with someone who responded to his initial question with "No comment, and that’s off the record, and don’t misquote me on that".

"I’ve never quite managed to achieve the full trifecta again," Gibb says with a chuckle.

"It did reinforce for me, don’t necessarily ask the H-bomb question first ... Warm things up a bit first."

So, where were you born? Where did you grow up?

Gibb was born in Greymouth, in June, 1952, the second child of a radio technician who later became a Presbyterian minister. Much of his early life was spent in Pine Hill, Dunedin; his teens at Mt Somers, in Canterbury, and Southland’s Bluff.

He credits his boyhood interest in writing to Clarence Beeby’s reforms of the New Zealand education system during the 1940s and 1950s.

"He was a brilliant educationalist who ... promoted creativity very actively."

For Gibb, the 1970s were consumed by university life, in Dunedin. He studied English and philosophy, tutored English, edited student publications including Critic, served on the student association executive and, in 1977, was selector-coach for the University of Otago’s successful University Challenge television quiz team.

His entrance to the world of paid reporting began with a chance conversation. A university anthropology department technician, Graeme Mason, who Gibb believes had previously been a newspaper sub-editor, asked the 20-year-old part-time interviewer of poets and artists whether he had ever considered journalism as a career.

Curiously, he hadn’t. But the thought stuck. Within months, Gibb gave up his job at Dunedin’s University Book Shop to train at the Wellington Polytechnic journalism school. Work at the Whanganui Chronicle, where one of his first assignments was a car crash involving a mother and her two children — "It’s almost too painful to recall" — was followed, in 1988, by a return south to the ODT.

"I’ve never really applied for a job. They just offered me the job at the Chronicle. And at the ODT, I was asked to come in for an interview."

The university was his round for 14 years. Then he focused on university research while also keeping his eye on Otago Museum and, later, Toitu Otago Settlers Museum. Along the way, he has also written more than 120 obituaries — "writing a decent obituary can be a painful process; you’re interacting with the family, you’re interacting with grief" — has covered emergency services, the ACC, the Otago Regional Council and has done a fair share of general reporting.

He twice interviewed Sir Edmund Hilary — "not only New Zealand’s greatest mountaineer ... but a kind of international ambassador for humanity" — and in 1991 won the New Zealand Institute of Physics writing award.

But Gibb’s highlights from almost 40 years of journalism coalesce around opportunities he has had to "champion the underdog".

"Not that I’m running a one-man ministry of lost causes ...," he says with a wry smile.

"I do believe in providing a voice for the voiceless.

"I think that’s an inherent part of journalism."

That view is reflected in his trade union involvement, which spanned four decades and encompassed workplace, regional and national roles.

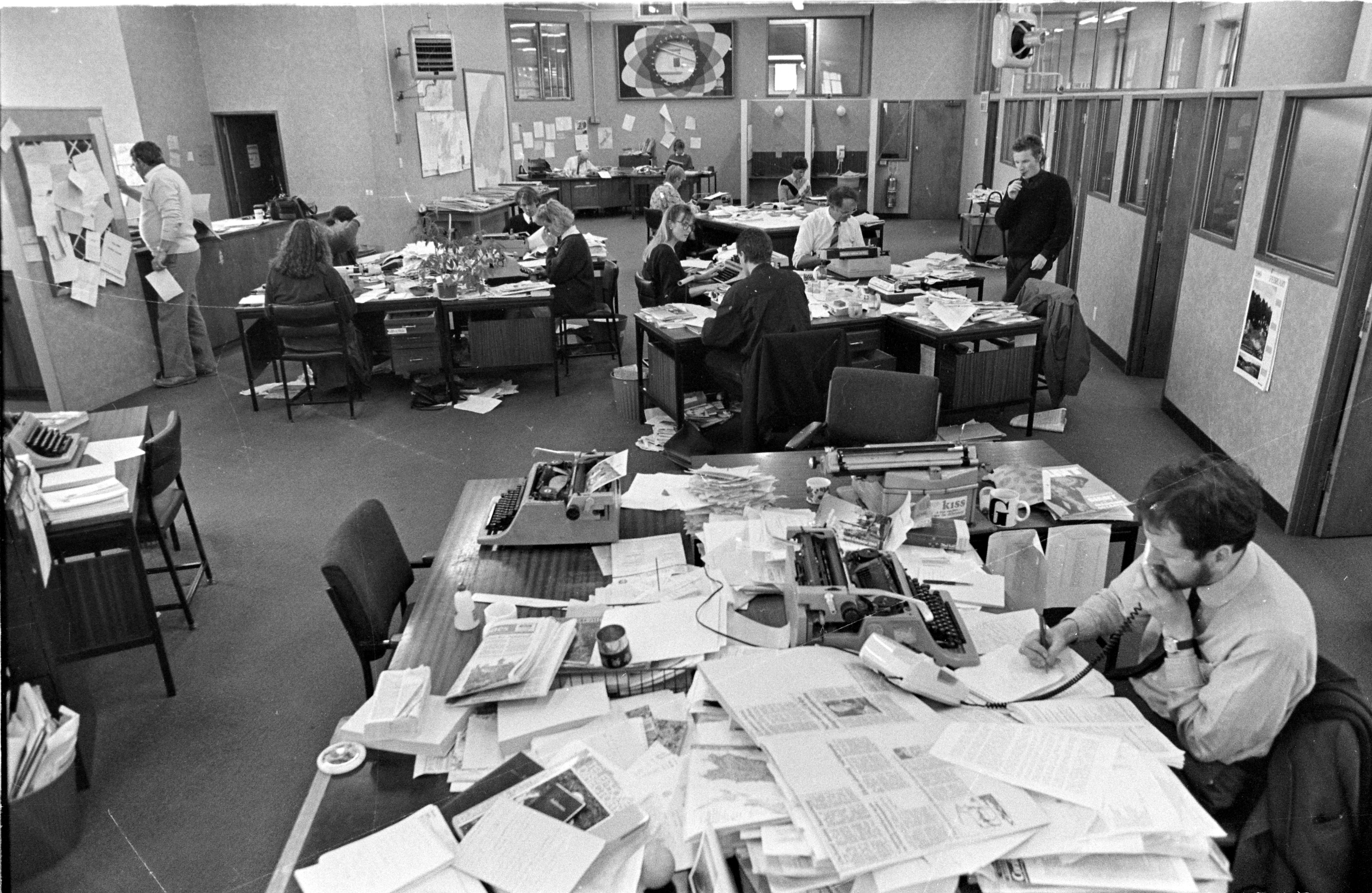

In print news media, much has changed. When Gibb started, tools of the trade were a landline phone, a typewriter, a pen and a notebook. Now, two phones and a computer complement pad and pen, with news not only printed but also online, updated constantly.

Unchanged, however, is the excitement of chasing stories, the pressure to get stories written — "It’s not exactly putting your arm in a meat grinder and twisting the handle, but ..." — and the essence of what the job is all about.

"Part of the magic of journalism is ... through some interviewing and a bit of tapping on a computer you can put some ideas out there, you can invite people to look at something afresh or for the first time.

"I think journalism does, generally speaking, leave the world a better place."

Gibb’s return to Dunedin was precipitated by the death of his father, Les, in late 1987.

"I wanted to be here to support my mother."

Gibb describes his late mother, Margaret, as an Anglophile, but admits both mother and son were keen on their cultural roots.

She started taking trips to the United Kingdom at the age of 60. He accompanied her on 13 visits, before she died in 2012. In all, Gibb has travelled to the Mother Country more than 20 times. There have also been plentiful side-trips to other spots in Europe.

He visited Australia early last year, just before the worldwide pandemic took hold, but has put global gallivanting on an indefinite hold.

"I don’t regard an agonising death as a particularly desirable feature of a holiday."

Gibb’s partner of many years is Kathy Batten.

She, he says, is "generally enthusiastic" about his retirement. He is more ambivalent.

"It is said that it is better to travel hopefully than to arrive. It’s going to be a big transition for me. I’m going from fulltime to nothing."

Not quite nothing. Writing will continue.

Poetry has been a passion since Gibb wrote his first stanza on his 20th birthday.

He has had two books of poems published; The Thin Boy & Other Poems (2014) and Waking by a River of Light (2017), both by Cold Hub Press. A third is being considered by a publisher.

"Creative writing is demanding ... it is a place, in a sense, of zero security.

"But being creative is part of being human, isn’t it."

At the museum morning tea in his honour, Gibb says a few words and reads a couple of his own poems.

Chasing the Shadow was chosen by fellow poet Brian Turner for inclusion in the 1991 edition of the annual Poetry New Zealand publication.

He was so busy that day

He left himself behind

Like a suitcase in a railway station ...

The second, To Fall Asleep on a Wide Beach, has unaccountably been read at several funerals, he says to gentle laughter.

His words express the way he views the world and the people who inhabit it.

Others present, adding to Dr Griffin’s words, express their views of Gibb.

"You really care about the details."

"You are a kind person."

"It has been good to work with someone who takes journalism seriously."

"Your name is now synonymous with a big part of the history of this place."

This is the second morning tea in his honour in two days, one of three during his final fortnight.

Before the abundant table can be plundered, Dr Griffin has a final comment.

Gibb’s most recent article has drawn attention, again, to regional museums’ lack of government funding despite the national treasures housed in their collections.

Feedback he has received since the story was published, Dr Griffin says, is that disclosures in it have ruffled feathers as far away as Auckland and that the topic has even been discussed in Cabinet.

"I think what you have done, John, is really important. It says things that need to be said. It speaks to the value of good journalism."